Copyright 2005, 2010 by Mike Ditka and Rick Telander

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, or otherwise, without prior written permission of the publisher, Triumph Books, 542 South Dearborn Street, Suite 750, Chicago, Illinois 60605.

Triumph Books and colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

This book is available in quantity at special discounts for your group or organization. For further information contact:

Triumph Books

542 South Dearborn Street

Suite 750

Chicago, IL 60605

Phone: (312) 939-3330

Fax: (312) 663-3557

www.triumphbooks.com

Printed in the United States of America

ISBN: 978-1-60078-508-5

Content packaged by Mojo Media, Inc.

Joe Funk: Editor

Jason Hinman: Creative Director

All photographs courtesy of the Chicago Tribune except where otherwise noted

The game summaries, Remembering 85 interviews, and statistical appendices appeared previously in The 85 Bears: Still Chicagos Team, copyright 2005 by The Chicago Tribune. Used with permission. Portions of the main narrative text appeared previously in the book, In Life, First You Kick Ass, copyright 2005 by Mike Ditka and Rick Telander.

To those men on the field who made this all happen, and to the memory of the Old Man.

M.D.

To the good life.

R.T.

Acknowledgments

I want to thank all of those writers who documented the Bears run to the Super Bowl, particularly the columnists and beat reporters for the Chicago Sun-Times, whose old news clips were so valuable in my research.

I also got insight and information from these books: Halas by Halas, by George Halas and Arthur Veysey; Ditka: An Autobiography, by Mike Ditka and Don Pierson; Papa Bear, by Jeff Davis; Its Been A Pleasure: The Jim Finks Story, by seven various writers; Ditka by Armen Keteyian; Singletary on Singletary, by Mike Singletary and Jerry Jenkins; and McMahon, by Jim McMahon and Bob Verdi.

Rick Telander

Table of Contents

Introduction

T o me, it seems like only yesterday that the Mike Ditka Bears ruled the earth. Part of that is because during the amazing and amusing 1985 season, I lived next door to the team. The east property line of my yard was the west end line for the Bears practice facility in Lake Forest. A chain-link fencewith a number of large, rusty-edged, human-sized holes in ita few ash trees, and some accidental buckthorn sprouts were all that separated my house from the gridiron.

My wife and I and our two baby girls had moved from a two-bedroom Evanston apartment in 1984, risking everything on a down payment and a strangling mortgage, heading farther north in the burbs where things were cheaper and we could affordstrange as it may seem now with current real estate prices in this areaour first house. The 100-yard grass field next door was vacant when we arrived in the spring of 1984. It was called Farwell Field, I learned, and belonged to Lake Forest College. Remarkably, the Bears shared the field all late summer and fall with the mighty Division III Lake Forest Foresters, a band of cheerful, red-and-black-clad, nonscholarship collegians about the size of average high school players. The Foresters would tear up the field on Saturday afternoons against Beloit and Lawrencereally destroy the sod when they played in the occasional monsoonand then the Bears would practice on the maimed surface the rest of the week. By late November the grass would be brown, clotted, and ruined. At the east end of the field was the low brick structure known as Halas Hall, with the large office window to the far south being that of young team president Michael McCaskey and the window to the north being that of young head coach Mike Ditka. In time I would realize that as I stood in our ground-floor bathroom when the leaves were gone, casually relieving myself, I could see into the working quarters of each man.

Of course, I didnt know much about this yet. I worked for Sports Illustrated at the time, and I loved sports. But mostly I traveled for my stories. To Washington and San Francisco and Pittsburgh, places where they had real NFL teams and real heroes. I had heard the Bears lived next door to our new place, but my mom had actually found the house and told me about it while my family was vacationing in Florida, and I made the earnest-money payment sight-unseen. At any rate, in May when our burgeoning troupesoon to be six of usmoved our few possessions into the old house on Illinois Road, nobody was in the big yard next door.

Who cared about the Bears, anyway?

The year before they had finished 88. In 1982, a strike-shortened misfire, they had gone 36. The year before that, 610. The year before that, 79. You threw in with the Bears at your own risk. They hadnt won anything since 1963, three years before the Super Bowl was invented.

Still, the Bears had this fellow named Payton. And they had a nostalgia-laden tradition. And starting in 1982 they had a new coach with fire in his eyes, a sometimes-frightening, sometimes-inspiring former All-Pro tight end by the name of Mike Ditka. He had replaced Neill Armstrong, coming straight from a special teams job with the Dallas Cowboys, apparently at old man George Halass request. Which made folks wonder if the acerbic, grumpy Papa Bear had finally gone around the bend. Special teams coaches didnt become head coaches. Offensive coordinators did. Defensive coordinators did. Special teams coaches became not much of anything.

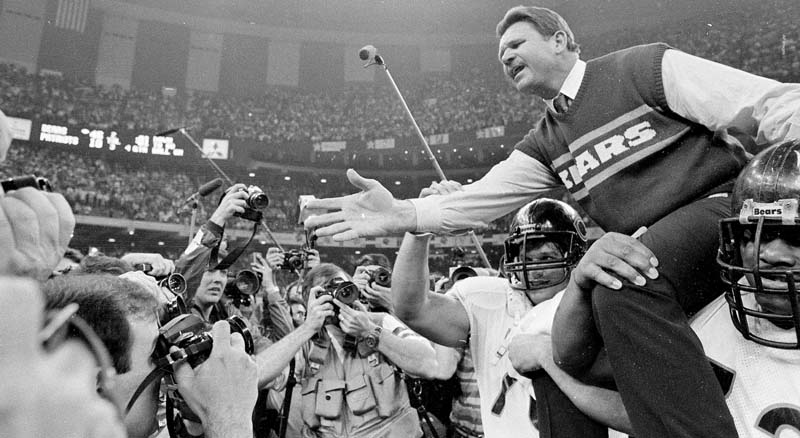

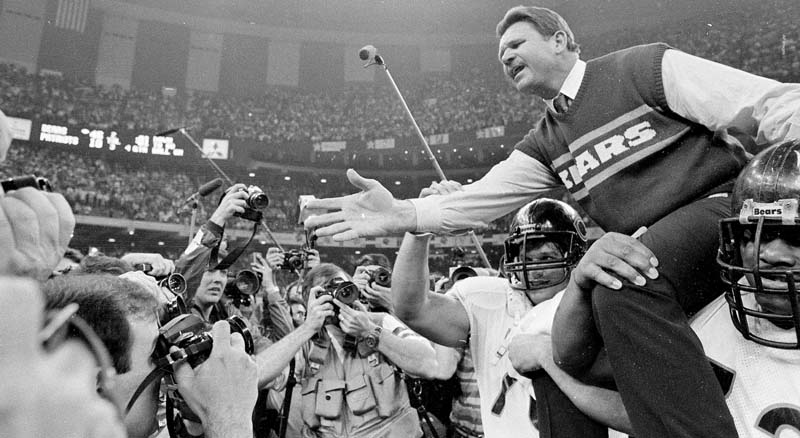

Ditka was a guy who broke racquets in rage when he played racquetball against Cowboys staff members like Dan Reeves and the great calm one himself, Tom Landry. Ditka made his Cowboys receivers run, and when they didnt run right, he swore at them. He challenged them to fight. Right there, on the spot! He turned red. He turned purple. As an athlete he had been overwhelming in high school, dominant at Pitt, ferocious in the NFL. In 1983, his second year as Bears head coach, he had been so infuriated after a loss, he punched a filing cabinet with his right hand, breaking a bone in the process. At the next game he inspired his team by saying, Win one for Lefty. He was perpetually agitated, outspoken, a puffing volcano always on the verge of eruption. This was the head coach of the storied Chicago franchise, the granddaddy of the league? Help.

But, Ditka knew what it meant to be a Bear. For six years, starting in 1961, he had played like a maniac, on and off the field. He defined toughness and grit at the tight end position. Despite his Pennsylvania steel town roots and accent, he came to embody the soul of the black-and-blue division Bears along with two other striving soulsGayle Sayers and Dick Butkus. Traded to the Eagles in 1967 and then to the Cowboys in 1969, Ditka played in two Super Bowls and was an assistant coach in two others. The idea of Ditka as a head coach seemedwhat would you call it?intriguing? What if his passion could be harnessed, focused, reproduced, and transferred like magic capes to all those players under him? What if

Nah.

Gradually the Bears began to make their presence known next door. There was a minicamp or two. And sometimes I would see Ditka in a golf cart on the edge of the grass, observing, gesturing, sometimes seated with oddball young quarterback Jim McMahon or even with the great, squirming Walter Payton himself. Sometimes I could hear Ditka yell. Sometimes I could see his orange or blue sweatshirt glinting through the bushes as he limped from drill to drill. He chewed gum constantly, as though his jaw had to move nonstop to compensate for the uncertainty of his football-ravaged hip joints. There were the usual practice noisesgrunts, whistles, hollerings, pads cracking, the leathery thud of punts departing Dave Finzers and later Maury Bufords foot and the four- or five-second delay before a reciprocating thud was heard as each ball touched earth.

Next page