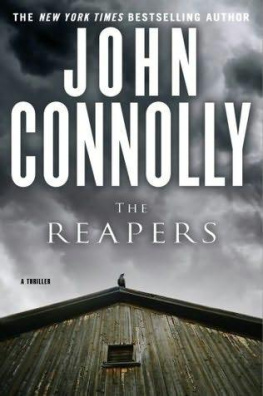

THE WHISPERERSJohn Connollywww.hodder.co.uk

About the Author

John Connolly was born in Dublin in 1968. His debut EVERY DEAD THING swiftly launched him right into the front rank of thriller writers, and all his subsequent novels have been Sunday Times bestsellers. He is the first non-American writer to win the US Shamus award. To find out more about his novels, visit Johns website at www.johnconnollybooks.com.

First published in Great Britain in 2010 Hodder & Stoughton

An Hachette UK company

Copyright John Connolly 2010

The right of John Connolly to be identified as the Author of the Work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

All characters in this publication are fictitious and any resemblance to real persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library

Epub ISBN 978 1 848 94216 5

Book ISBN 978 0 340 99350 7

Hodder & Stoughton Ltd

An Hachette UK Company

338 Euston Road

London NWl 3BH

www.hodder.co.uk

To Mark Dunne, Paul OReilly, Noel Maher and

Emmet Hegarty: princes all.

Extract from A Terrible Love of War

by James Hillman 2004.

Published by Penguin Books.

Prologue

War is a mythical happening.... Where else in human experience, except in the throes of ardor... do we find ourselves transported to a mythical condition and the gods most real?

James Hillman, A Terrible Love of War

Baghdad

16 April 2003

I t was Dr. Al-Daini who found the girl, abandoned and alone in the long central corridor. She was almost entirely buried beneath broken glass and shards of pottery, under discarded clothing and pieces of furniture and old newspapers used as packing materials. She should have been rendered almost invisible amid the dust and the darkness, but Dr. Al-Daini had spent decades searching for girls such as she, and he picked her out where others might simply have passed over her.

Only her head was exposed, her blue eyes open, her lips stained a faded red. He knelt beside her and brushed some of the detritus from her. Outside, he could hear shouting, and the rumble of tanks changing position. Suddenly, bright light illuminated the hallway, and there were armed men shouting and giving orders, but they had come too late. Others like them had stood by while this had happened, their priorities lying elsewhere. They did not care about the girl, but Dr. Al-Daini cared. He had recognized her immediately, for she had always been one of his favorites. Her beauty had captivated him from the first moment he set eyes on her, and in the years that followed he had never failed to make time to spend a quiet moment or two with her during the day, to exchange a greeting or merely to stand with her and mirror her smile with one of his own.

Perhaps she might still be saved, he thought, but as he carefully shifted wood and stone he recognized that there was little he could do for her now. Her body was shattered, broken into pieces in an act of desecration that made no sense to him. This was not accidental, but deliberate: he could see marks on the floor where booted feet had pounded upon her legs and arms, reducing them to fragments little larger than the grains of sand on which she now rested. Yet, somehow, her head had escaped the worst of the violence, and Dr. Al-Daini could not decide if this rendered what had been visited upon her less awful, or more terrible.

Oh, little one, he whispered as he gently stroked her cheek, the first time that he had touched her in fifteen years. What have they done to you? What have they done to us all?

He should have stayed. He should not have left her, should not have left any of them, but the Fedayeen had been battling the Americans near the Ministry of Information, the sounds of gunfire and explosions reaching them even as they sandbagged friezes and wrapped foam rubber around the statues, grateful that they had at least managed to transport some of the treasures to safety before the invasion commenced. The fighting had then spread to the television station, less than a kilometer away, and to the central bus station at the other side of the complex, drawing closer and closer to them. He had argued in favor of staying, for they had stockpiled food and water in the basement, but many of the others felt that the risks were too great. All but one of the guards had fled, abandoning their weapons and their uniforms, and there were already black-garbed gunmen in the museum garden. So they had locked the front doors and left through the back entrance before fleeing across the river to the eastern side, where they waited in the house of a colleague for the fighting to cease.

But it did not stop. When they attempted to return over the Bridge of the Medical City they were turned back, and so they stayed with their colleague once again, and drank coffee, and waited some more. Perhaps they had remained there for too long, debating back and forth the wisdom of abandoning what was, for now, a place of safety, but what else could they have done? Yet he could not forgive himself, or assuage his guilt. He had abandoned her, and they had had their way with her.

And now he was crying, not from the dirt and filth but from rage and hurt and loss. He did not stop, not even as booted feet approached him and a soldier shone a flashlight in his face. There were others behind him, their weapons raised.

Sir, who are you? asked the soldier.

Dr. Al-Daini did not reply. He could not. All of his attention was fixed on the eyes of the broken girl.

Sir, do you speak English? Ill ask you one more time: who are you?

Dr. Al-Daini picked up on the nervousness in the soldiers voice, but also the hint of arrogance, the natural superiority of the conqueror over the conquered. He sighed, and raised his eyes.

My name is Dr. Mufid Al-Daini, he said, wiping his eyes, and I am the deputy curator of Roman antiquities at this museum. Then he reconsidered. No, I was the deputy curator of Roman antiquities, for now there is no museum left. Now there are only fragments. You let this happen. You stood by and let this happen....

But he was speaking as much to himself as he was to them, and the words turned to ash in his mouth. The staff had left the museum on Tuesday. On Saturday, they learned that the museum had been looted, and then began to return in an effort to assess the damage and prevent any further theft. Someone said that the looting had commenced as early as Thursday, when hundreds of people had gathered at the fence surrounding the museum. For two days, they were free to ransack. Already, there were rumors that insiders had been involved, some of the museums own guardians targeting the most valuable artifacts. The thieves took everything that could be moved, and much of what they could not take they attempted to destroy.

Dr. Al-Daini and some others had gone to the headquarters of the Marines and pleaded for help in securing the building, for the staff was fearful that the looters would return, and the US Army tanks at the intersection only fifty meters from the museum had refused to come to their aid, citing orders. They were eventually promised guards by the Americans, but only now, on Wednesday, had they come. Dr. Al-Daini had arrived just shortly before them, for he had been one of those assigned the role of liaison with the soldiers and the media, and had spent the previous days being passed up and down the military ranks, and providing contacts for journalists.

Next page