For my family Steve, Scott, and Ric.

The few become fewer.

For my aunts and mother, the four sisters of the Apocalypse, living large at the time of the Depression and conquering at the time of war. The world has become a lesser place in your absence.

For Katie Anne, Brandon Lynn, Shaune David, and Cindy Michelle my children.

I would like to take time out to thank my editor, Pete Wolverton; without Pete and his guidance, all would be lost. Also to Katie at Thomas Dunne, forever answering the mundane questions of the unenlightened.

Finally, to the United States Navy, consistently setting the standard among the American armed forces for professionalism and foresight. To the blue ocean and brown water navy, without whose cooperation this book would not have been possible.

PROLOGUE

FRANCISCO PIZARRO

A quest for the riches of the earth brought them to the waters of legend and the greed of man came and destroyed the way of innocence, and the ancient one rose from the depths to consume them.

FATHER ESCOBAR CORINTH, CATHOLIC PRIEST TO THE FRANCISCO PIZARRO EXPEDITION

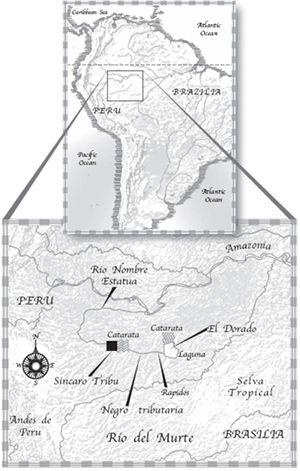

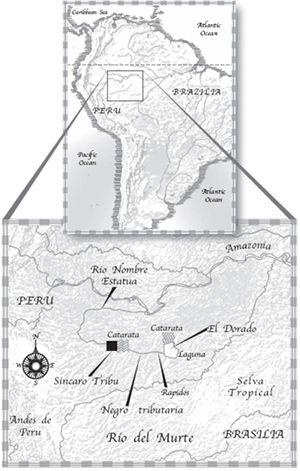

AMAZONIAN RIVER BASIN SUMMERAD 1534, 56 DAYS OUT OF PERU

The Spaniards let loose a volley of musket fire into the endless green of the jungle, not knowing if their lead shot struck anything more vital than fern or moss. Even before the acrid smoke was cleared by the slight breeze that reached the floor of the small valley, the soldiers had turned and continued their flight, four and five men at a time, while a like number reloaded and covered their retreat. The captain ventured a look back to make sure all of his soldiers had safely vacated their positions, then he quickly followed to catch up with them.

The deeper they fled into the surrounding jungle, the denser it became, effectively choking off their escape route with natural tangle-foot of vines and small trees. Above them, the sun was slowly being smothered by the trees that seemed to grow together, creating a false roof that offered no sanctity of protection. The river offered the only clear avenue of escape.

The captain had but two choices: stay here and stand their ground against arrow and dart while taking and losing more lives, or go into the river, where they would be more exposed yet could make better time than they would while also fighting the thickening growth around them.

"Into the water, men. Why do you delay? We must follow the river, it's our only route!"

"Look, my captain," Lieutenant Torrez said, pointing skyward.

When Captain Hernando Padilla looked up, his eyes widened at the monstrous sight. Towering above the Spaniards two sixty-foot-tall stone carvings rose above the giant trees on either side of the river. The expedition had never seen the like of them. The carvings were manlike in stature, only the heads were not that of any men or any of the Incan gods the soldiers had seen thus far. The lips were thick, and the deep etchings in the rocks depicted scales where flesh should have been. The heads of both giant figures stared down upon the intruders with the large eyes of a fish. They were ancient stone deities, guardians of the vegetation-choked waters of the darkened river beyond. Vines entered and exited the cracked and age-worn stone like snakes emerging from holes.

"They are only stone imaginings of heathen people," Padilla shouted. "Get these men into the water, Lieutenant, now."

Just as he had uttered the orders to advance, an arrow glanced off his armor from behind and ricocheted into the air. The captain almost lost his balance as he bent over, cursed, and then quickly recovered. Small darts started to strike the spit of sand and moving water around the Spaniards. The Indians were upon them once again, not only shooting their primitive arrows, but launching from long blow guns small darts tipped with the poison of exotic frogs the very same devices the soldiers had seen the native peoples use frighteningly well during their time with the tribe. They knew it would be a slow death if even one dart pierced their exposed flesh. The men needed no more coaxing or threats. As the huge stone edifices watched on either side, they splashed into the swirling water and made their way into the shadows of the canyon.

* * *

The Spaniards traveled between massive trees that cut off the sky. They marched most of the late afternoon, enduring sporadic attacks from Sincaro emerging from the thick undergrowth beneath the trees. Then the Indians vanished just as abruptly into the jungle. It had been close to an hour's time since the last ambush, but the Spaniards were still expecting the next attack at any moment. As they progressed, the sky ahead of them was slowly being shut out by the jungle and towering trees from both sides of the river. They heard with ever-increasing volume the more pleasurable sounds of animal life, as a semblance of normalcy returned to their surroundings after their headlong flight. Until this point they had noticed no sound of life other than their own shouts and curses during the assaults they had endured the last few hours.

Finally they fought their way past the raging rapids that had appeared suddenly. The violence of the waters had terrified the men, who were lucky to spy a small wedge of beach along which to pass.

The captain called a halt and rested his worn body against the trunk of a large tree. The nightmare visions of the murder of so many innocents churned over and over in his mind, threatening to drive him mad. He lowered his head with shame at what they had done. The orders for the excursion into these unknown lands to the east had been given to him personally by Pizarro. The words of that order now echoed through his memory: The Indians are not to be thought of as allies. They must be subdued with forthright action and intimidation until such a time as the source of the gold is obtained. If this course of action cannot be maintained, assistance shall be called for immediately. The location of El Dorado is paramount above all other considerations.

But Padilla had found the Indians to be gracious and kindly toward the visiting strangers. So he had changed his tactics and tried to gain the advantage in his own manner, ignoring the orders of the madman in the east.

Padilla angrily removed his helmet and harshly rubbed the sweat from his face. The heavy iron soon slipped from his slick fingers and fell to the green jungle floor. The Spaniard ignored it as he instead looked skyward, trying desperately to penetrate the deep canopy of green for just a small glimpse of the blessed sun. But it was as hidden, removed from the world as he knew the grace of God would be forever removed from his soul.

For three months they had endured the hellishness of the Peruvian mountains and Brazilian jungle, only to find they were alone in the most godforsaken area the expedition had ever known. Only the good nature of his men, grateful to be away from the slave master Pizarro, had kept his small company in line. Then one evening they had come upon a most wondrous valley, full of exotic flowers, tall leaf-laden trees, and the blessed sun. It was here they had found the Sincaro; the dwarf Indians that inhabited the beautiful valley. The small people met them with trepidation at first. Against orders, Padilla had eventually gained their trust through trading and the honest goodwill of his men. They treated the Sincaro with respect and gentleness, and the small men and women of the village slowly welcomed the tall strangers as friends.

These prehistoric tribesmen were a hardy people and, according to their stories and legends, had been so since they had been enslaved by the empire to the west. They had gained their freedom thanks to the river gods who had dealt their Inca taskmasters a savage blow a hundred years before, which had finally freed the small people. When asked how their river gods had achieved this, the elder of the village would answer only that the Inca had gained the secret knowledge of the Sincaro through murder and slavery, and had even tried to chain their deities and turn them on the Sincaro in the Incan pursuit of earthly riches. The river gods would not become the slaves of men, and they revolted. Then the Inca were no more. The old man would smile at that point when he saw the skeptical looks of the Spaniards. The Inca had never returned to the valley, and now it was the captain who would have to gain the trust of these strange and vibrant people to learn the secret that had brought and then driven the Inca from these lands.