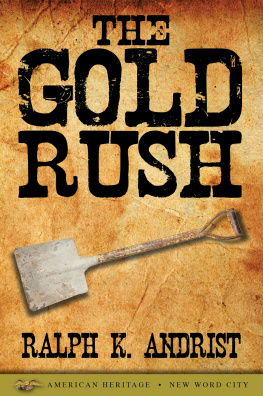

THE RUSH FOR GOLD!

On a frigid day in Coloma, California, James Marshall's heart pounded. An excitable man, he held a shiny, metal nugget in his hand. Could this be gold? To test the metal, he hammered it with a rock. It flattened easily, as gold should. When news spread of Marshall's discovery, thousands of people traveled to the Wild West in search of fortune. Author Jeff Savage explores the miners, prospectors, and families, who went great distances to find gold. Although most people never found it, the gold rush would change the landscape of the United States forever.

About the Author

Jeff Savage has written more than two hundred books for students. Jeff lives with his wife, Nancy, and sons, Taylor and Bailey, in El Dorado Hills, a stone's throw from where gold was discovered in California.

James Marshall strolled about, breathing in the frigid air, inspecting the grounds, as he did every Monday morning. The men on his crew prepared for another hectic workweek. They were building John A. Sutters water-driven sawmill.

About fourteen thousand United States citizens lived in California at the time. On January 24, 1848, something was about to happen in the sleepy town of Coloma that would change everything.

Marshall examined the newly built tailrace, the small canal that discharged the water leaving the mill. Three days earlier, the workmen had dammed the south fork of the American River in order to direct a flow of water through the mill. Marshall saw that the tailrace was working well.

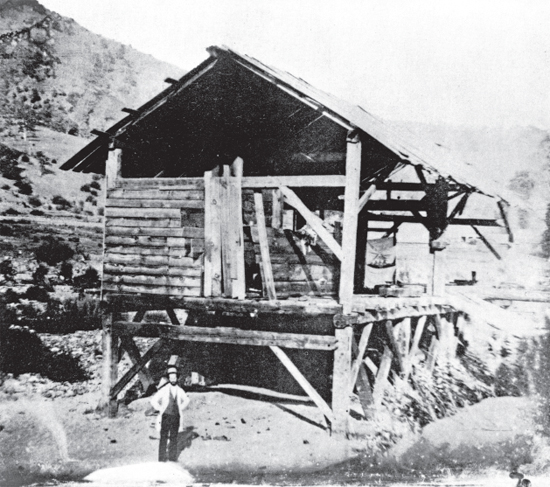

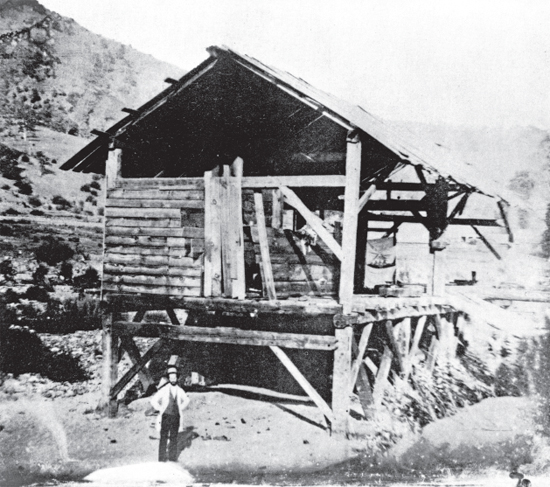

Image Credit: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs

James Marshall is pictured standing in front of John Sutters sawmill in Coloma, California, where he discovered gold.

That was not all he saw. The river had swept away rock and rubble, leaving silt in part of the tailrace. Marshall glanced up at the dam, then back at the sawmill and tailrace. Looking closely at the silt and noticing something shining in the early morning sun, he wondered if he could be seeing things. He squinted as he looked even closer at the silt. The dirt sparkled.

Marshall scraped up some of the silt in his hand and rubbed it with his fingers. Shiny flakes and small nuggets separated from the dirt.

For years, Marshall had heard rumors about gold in the foothills of the Sierra Nevada mountain range. Could this be gold? He bent over and gathered up more silt. More small gold nuggets appeared. James Marshall was an excitable man to begin with. On this morning, his heart was pounding. He grabbed a rock and hammered a nugget with it. The gleaming metal flattened easily, as gold should. Fools gold, which looks like real gold but is worthless, would have broken into bits. Marshall was sure now that he had discovered gold!

For two days, Marshall wondered what to do. Should he tell the workmen? What if they killed him and hoarded all the gold? Should he keep the secret to himself? How would he be able to concentrate on building the sawmill? Finally, he decided to tell his boss, John Sutter.

Marshall rode forty-five miles to Sutters Fort, arriving there on January 28. He was sweating from excitement as he burst into Sutters office.

He told me he had something of the utmost importance to tell me, Sutter wrote in his diary, that he wanted to speak to me in private, and begged me to take him to some isolated place where no one could possibly overhear us.

Sutter and his bookkeeper were alone in the house. Marshall insisted on going upstairs with his boss, and Sutter obliged. The two men entered a private room. Marshall began to tell of his discovery. He took a piece of cloth from his pocket and began unfolding it. Suddenly, the bookkeeper walked in to ask Sutter a question.

My God, didnt I tell you to lock the door? Marshall yelled.

The two men looked in Sutters encyclopedia for some of the different ways to test gold. They pounded the nuggets and weighed them in water. They dipped them in nitric acid to see if they resisted corrosion; Gold would not come apart in the strong, toxic acid. The nuggets passed all the tests. Marshall definitely had found gold.

Marshall returned to Sutters Mill, where he told the workmen about his discovery. At first, they were not excited. They continued to build the mill and only dug for gold on Sundaytheir day off. When the mill was finished, some of the men began to spend all their time prospecting for gold. The news spread to San Francisco and eventually to the East Coast. Most people did not believe that gold had been discovered. They thought it was a trick to get people to settle in California.

Reports continued to be published. A letter was printed in the November 1848 issue of the American Journal of Science and Arts. The last paragraph read: Gold has been found recently on the Sacramento, near Sutters Fort. It occurs in small masses in the sands of a new millrace, and is said to promise well. Still, most of the eight hundred people who lived in San Francisco didnt react.

Then one day, a man named Samuel Brannan got people excited. Brannan lived a few miles below Sutters Fort, and he had opened a supply store for miners. Not many customers came. So, Brannan filled a bottle with gold dust and rode to San Francisco. He walked up and down the streets, held the bottle of gold dust high over his head, and shouted, Gold, gold! Gold from the American River! Before long, fewer than a hundred people were left in San Francisco. The rest were digging for gold near Sutters Mill. First, of course, they stopped for supplies at Sam Brannans store.

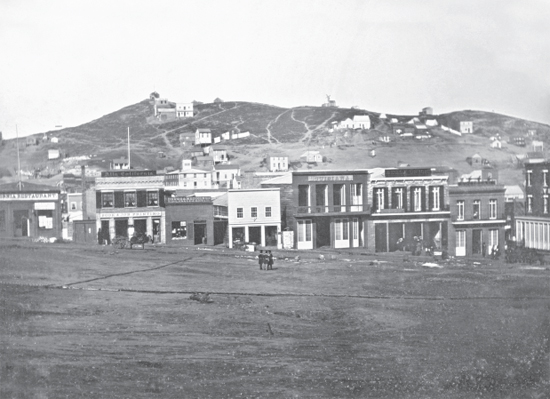

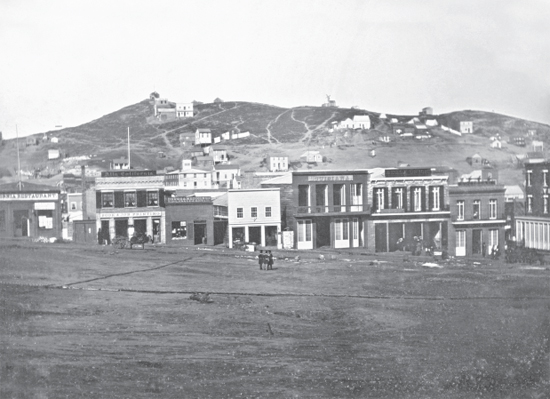

Image Credit: Courtesy Everett Collection

A view of San Francisco in 1851. After gold was discovered, many people left San Francisco to go to Sutters sawmill in search of gold.

Easterners began taking this gold talk seriously. Wild tales were being spread, first of nuggets of gold, then boulders of gold, then mountains of gold, and rivers gleaming with gold. The rush was on!

John Sutter was disappointed that gold was on his property. He owned thousands of acres of land that he named Nueva Helvetia (Helvetia is the Latin name for Switzerland, the land of his ancestors) and filled it with horses, cattle, mules, sheep, and hogs. Sutter just wanted to manage his land and watch his herds increase. For him, this gold rush could spoil everything.

The gold discovery of 1848 came as no surprise to some. American Indians probably knew for centuries about gold in the area, but they had no use for it. Mexican authorities used it in small quantities for jewelry and decorations. Yankee traders from the East would take home tiny nuggets or flakes, mainly as souvenirs. The American Indians and Mexicans also knew that news of a gold rush would lure thousands of white settlers.

In fact, gold had been mined in California some years earlier. Francisco Lopez, a Mexican cattle rancher, discovered gold northwest of Los Angeles, in the San Fernando Valley, on March 9, 1842. Lopez was returning home that day from tending his cattle in Placerita Canyon. On the way home, he remembered to pick some wild onions for his wife. As he pulled the onions out of the ground, Lopez noticed that shiny particles were attached to the onion roots. He had found gold! A local gold rush followed, and the land was worked over.