Introduction

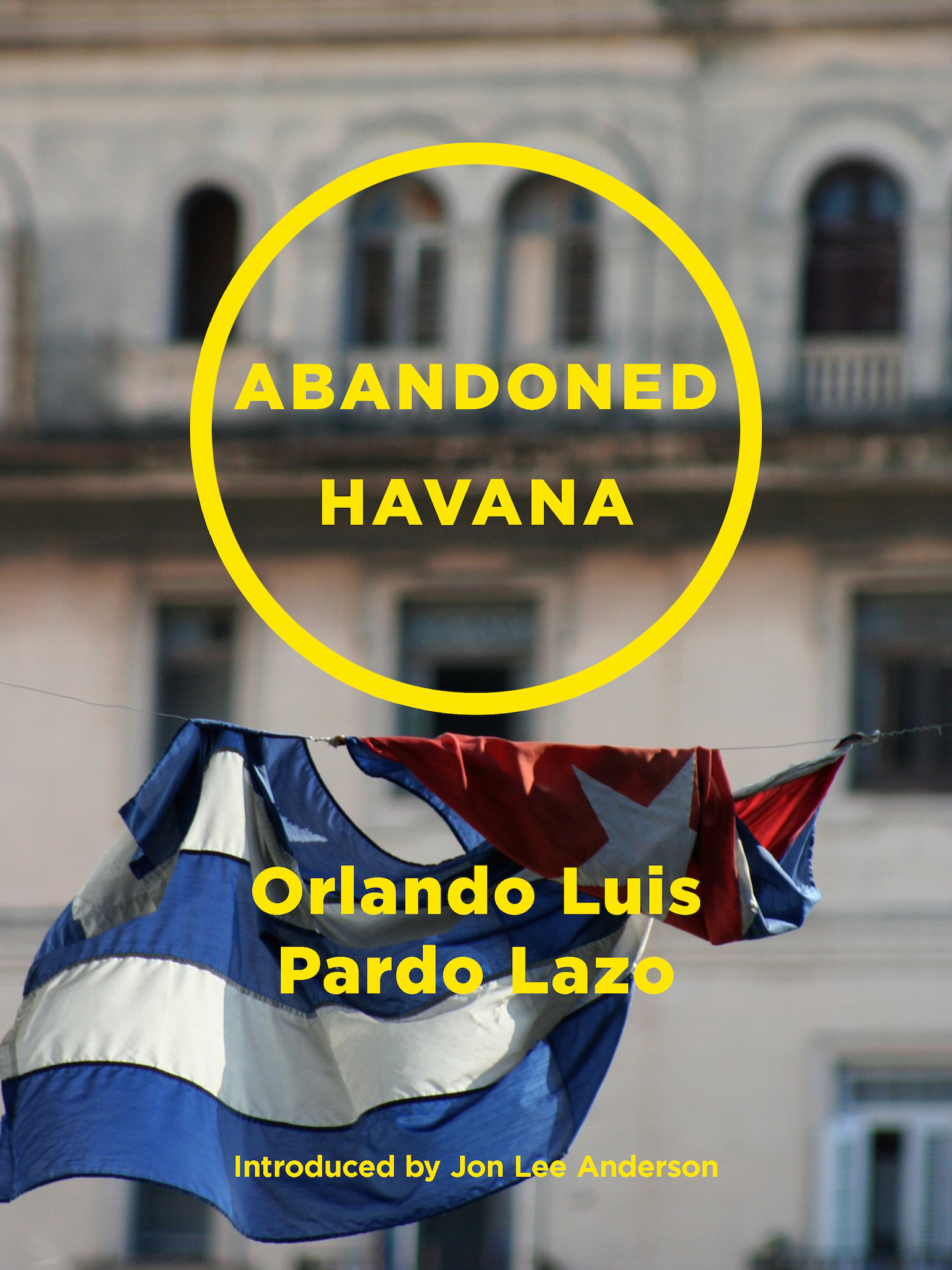

The distressed beauty of Cubas capital city has acquired an aesthetic symbolism that is as universally recognizable as it is fought over. At its core, the debate comes down to whether Havanas state of penury is self-inflicted or the consequence of externalread: Yankeeperfidy. Whatever the greater truth, Havana has come to resemble an eternally suspended Titanic, forever caught in the act of sinking, a repository of thwarted dreams and lingering nostalgias. This image holds true both for those who have left and for those who have stayed behind.

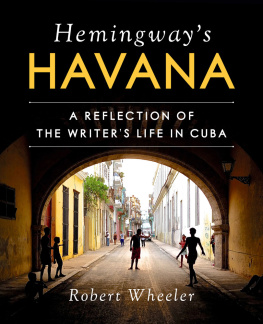

The eighty images in this book are unmistakable depictions of contemporary Havana. But this is not the iconic Havana of the soft-focus guidebooks, of the garish 50s Chevys, young lovers on the Malecn, and wizened cigar rollersalthough they too exist, just out of frame. The Havana of Orlando Luis Pardo Lazoor OLPL, as he refers to himselfis post-utopian, a city full of empty spaces and idle people, the consequences of a political system that has been on life-support for years but refuses to die.

OLPL calls himself a writer, blogger, photographer, and social activist. He was born in 1971, which means that he was twenty when the Soviet Union precipitously collapsed and Cuba was left without the economic subsidies it had depended upon since the early 1960s. Massive shortages of food and fuel led to several years of serious hardship, known as the Special Period, and caused widespread social discontent. In 1994, there was rioting, and tens of thousands of Cubans fled the island in a traumatic three-week maritime exodus by raft. Since then, the persistent lack of opportunities in socialist Cuba have led many more young Cubans to leave in the hopes of forging new futures abroad. Some have returned, but most have not.

For those who have chosen to stay in Cuba, the greatest challenges are those involved in making ends meet. For some, so too are the politics. Living as they do within a political system that does not tolerate the public expression of independent points of view, most Cubans have learned to keep their criticism to themselves. A small number, including Orlando Luis Pardo Lazo and his renowned contemporary and fellow blogger, Yoani Sanchez, have chosen to defy the status quo by writing what they actually think and believe. In 2007, Sanchez launched her blog Generacin Y , and in 2010, OLPL created Voces , Cubas first e-zine, intended as a critical online platform for Cuban voices. The two have paid a real world price for their virtual freedom. They are officially pariahs, and because of the islands restricted Internet, they remain largely unknown to most of their fellow citizens. Occasionally, things go even further. OLPL and Sanchez were detained together and roughed up by state security agents in 2009, and in 2012, OLPL was again briefly detained.

In the past couple of years, however, the pressure seems to have eased up for the dissident bloggers. In addition to an accelerating package of economic reforms that has included a gradual lifting of restrictions on Cubans owning small businesses, possessing cellphones, and traveling abroad, President Raul Castro has called for greater openness in Cubas state-controlled press. While many Cubans remain uncertain as to what this ultimately means, there does appear to be a greater tolerance by the government for expressions of public criticism. In 2012, in what many saw as an official gesture of reconciliation with the islands intellectuals, Cuban writer Leonardo Padura was awarded the National Prize for Literature despite the fact that his 2009 novel El hombre que amaba a los perros (The Man Who Loved Dogs) contained harsh critiques of Cubas cultural repression in the 1970s. In 2013, activists like Yoani Sanchez who were previously denied their passports by Cubas government were allowed to travel abroad and to return home without hindrance, and this year, Sanchez launched Cubas first-ever digital daily newspaper, 14ymedio . And OLPL carries on too, publishing a torrent of his own thoughts and those of others in Voces, and on his other websites, Lunes de Post-Revolucin and Boring Home Utopics . So far, so good. If they are allowed to continue, sites like Sanchezs and OLPLs can pave the way for the kind of open public debate that Cuba needs for a healthy future society.

***

Orlando Luis Pardo Lazo frets about Cubas destiny in the coming post-Castro years. He worries that a benumbed uniformity has taken root among his countrymen and has doomed them to a fossilized future. His sour portrayals of Havana seem aimed at illustrating his thesis that all is already lost. Many of his images are framed off-center or askewopportunistic snaps that illustrate a place suspended in time, and of the moments in peoples lives that speak to a deranged continuum. In one, an old man in shorts dances flamboyantly as he flattens tin cans by rolling a stick over them; in another, a pigeon has been cruelly crucified, its spread wings nailed to a telephone pole. A lone woman walks in front of a billboard that proclaims unity in the face of Yankee interference.

Abandoned Havana is an exercise in denunciation and indictment against those OLPL blames for his citys mortal affliction. They are, of course, the two Castro brothers, Ral and Fidel, who have determined the destiny of Cuba for nearly sixty years. But OLPL also blames his fellow Cubans. I live on a monolithic island whose monochrome monologue has made so many citizens brainless, he writes. Casting a bleak eye to the future, he adds: We will have to be very creative to escape the Castroism without Castros about to be imposed on us, [because] Castroism is unchangeable, indefatigable, incommensurable and [has] already won the fight against its own people.

In spite of OLPLs pessimism, a bittersweetness pervades some of the vignettes that accompany his photographs. It is as if, like a jilted lover, he still carries a wan hope for eventual reconciliation. In one entry, he depicts himself walking hand in hand with his girlfriend, and as they do she asks him what has happened to their city:

Landy, people lived here who thought that the Havana they made would last forever, she tells me, and now its like visiting an endangered species in the zoo, or walking though the ruins of an already extinguished planet. Youre a writer, someday will you tell explain to me what happened to us?

Of course my love, I tell her, and kiss her lips. But if there is something I understand from all these dialogues between one corner and the next in Cuba, it is that no kiss will save our Havana from heartbreak.

***

As is true of all lamentations, however, this book is also a tribute. There is no doubt that to Orlando Luis Pardo Lazo, Havana is a beloved place. To explain his photograph of the grand front steps, or Escalinata, of the University of Havana, where he once studied biochemistry, OLPL recalls moments of young love and ends on a note not of sourness but of yearning for bygone youth: Only the Alma Mater remains young there, gazing out at so much virginity of body and spirit. And in his ode to Cubas cemeteries, The Trumpets Sound of Silence, OLPL is full of reverence about the one place he knows that frees him from his brooding sense of loss and entrapment. Cuban cemeteries are beautiful, he writes. Cuban burial grounds are our territory for sincerity, a place where the historical little social games end. Capitalism and communism and the rest of human violence and stupidity are left outside the gates. And of his father, OLPL writes that he never learned how to say La Revolucin with conviction, but his eyes would tear up whenever he whispered La Habana