To Kim and Nicholas, who make everything possible, and to Sebastian and Paul, who were too young to die.

The cameraman was filming me. He must have thought I was one of them. I didnt look as badly wounded as the others so he didnt linger long, moving off to the next room where people were more photogenic because they were lying in their own blood.

I had done it often myselfwalked round war zone hospitals looking for shots with the most pathos. Too much injury was bad: you couldnt show it. Blood without the gore usually got through. Screaming or moaning was best: it gave viewers a feeling of the pain and horror and they could imagine the wounds that caused it.

The moaning today was different. I wasnt sure if it was the woman with the mutilated leg, or the man with the wounded stomach, or the other man whod been shredded by shrapnel, or my neighbour lying on the floor beside me. The explosion had wrecked my hearing and everything sounded muffled, even someone wailing just a bodys length away.

There was a voice in my head, too. It was my own, trying to tell me I wasnt here. This isnt real. We dont get hurt. Its not our world. We both have babies. Paul has a little girl.

It was only the third day of the Iraq war and the fighting had barely begun. I was in Kurdistan, the part that was supposed to be relatively safe. We had brought gas masks, thinking there might be chemical weapons strikes, but I wasnt supposed to be lying bleeding in a hospital near the body of my friend. This wasnt supposed to happen.

I looked up and the cameraman was filming me again. I recognised him as the BBCs shooter. I looked straight into his lens and he glanced up startled. Im a journalist, I said. I met you yesterday. Do you remember my cameraman, Paul? Hes dead. He said something about being sorry and asked if he could help me but I was seeing the explosion again and it overpowered everything.

We had been the last to drive to the militants base after the Americans bombed it because we wanted to be sure it was safe. That made us the last ones there. In another minute we would have been gone. Paul was getting some last shots of civilians driving out. He walked a few steps in front of me following some action when a car pulled up beside him and blew up.

For a moment I couldnt understand what was happening. I saw the car explode into a ball of flame. I felt the blast wash over me. I watched as parts of the car flew towards me and struck me in the chest. I heard the ringing in my ears and felt the blood all over me. I saw the people around me dead and dying. I felt shock greater than anything Id ever known. Then I saw Pauls body on the road and I knew the worst thing in the world had just happened.

A doctor was beside me now; he spoke some English. How are you feeling? he asked. I just nodded. We have a special room for you upstairs. I didnt feel deserving of anything special but I wanted to get away from the moaning and I knew I had to make some more phone calls to tell people I was alive. The doctor helped me up the stairs.

There had been nobody to call for help after the car blew up and I couldnt have called anyway because the blast had melted my satellite phone. As soon as Id reached the nearest town, Id borrowed a satphone from the first journalist I saw. Shed had to dial the number because my hands were covered in blood and shaking badly. The first person I rang was the ABCs Head of International Operations, John Tulloh. I wanted to sound in control but I was sinking into a black hole and could barely get the words out.

I have terrible news, I said, sobbing. PaulPauls dead.

Then I rang my wife Kim. She was staying at her parents house in Melbourne. It was one in the morning and the answering machine cut in, so I kept saying, Im OK, but Pauls dead, until she came on the line and started crying too. Later I rang my father and asked him to call my sisters, because I couldnt say any more to anyone.

I was in the special room upstairs now and it was full of people staring at me. Most of them were journalists; genuinely shocked, wanting to help, feeling it could have been them, but still working, still getting quotes. I told them I had a three-month-old son and Paul had had a six-week-old daughter. I asked them not to mention Pauls name yet because the ABC couldnt reach his wife, Ivana, and I didnt want her to learn her husband was dead by hearing it on the radio.

I was feeling nauseous again and wanted to vomit. The doctor came in and insisted that I have an injection. I remembered the battlefield first-aid courses where they told us to carry our own syringes because war zone hospitals sometimes reused them and you could catch HIV. But the other journalists said the syringe was new and clean, so I let him shoot me up with antibiotics, painkiller and Valium.

I told them what had happened at the checkpoint and how Paul had talked so much about his daughter. But the question none of the journalists asked, because they all knew the answer, was why we had left our children to come to Iraq.

On my last night in Australia, my wife and father and sisters had asked again and again why I was going. I told them it was my job and I was expected to go, but the truth was that Id pushed to go and the thing that had scared me most was that I could miss out on covering the worlds biggest story. I had been a foreign correspondent for seven years and it was a competitive, all-consuming business. If you werent covering the major events, like wars or revolutions, you felt left behind. There was nothing worse than sitting in a bureau doing nothing while your friends and colleagues flew off to the latest trouble spot. Id reached a stage where I no longer thought it strange to leave a wife and baby to go to a war.

I assumed Paul had felt the same but we hadnt got round to discussing it. I had come to think of him as a friend, as happens quickly in intense situations, but I had known him only four days. Thats how long wed been in Iraq.

The voice came back to me. I shouldnt be here.

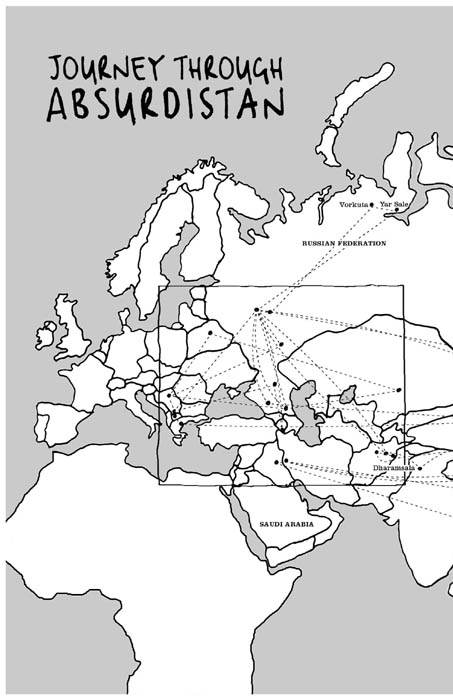

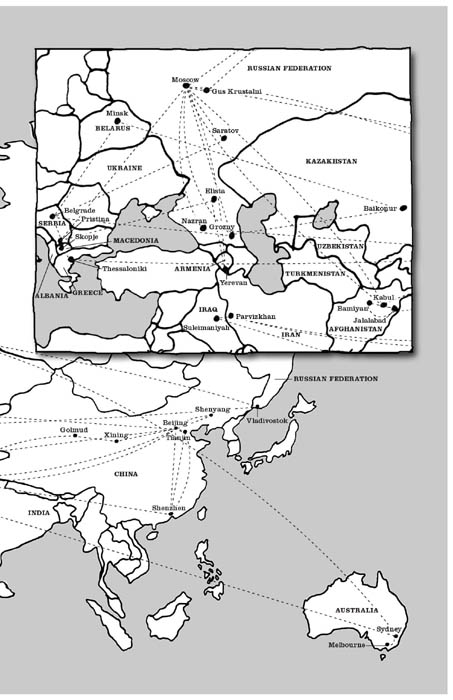

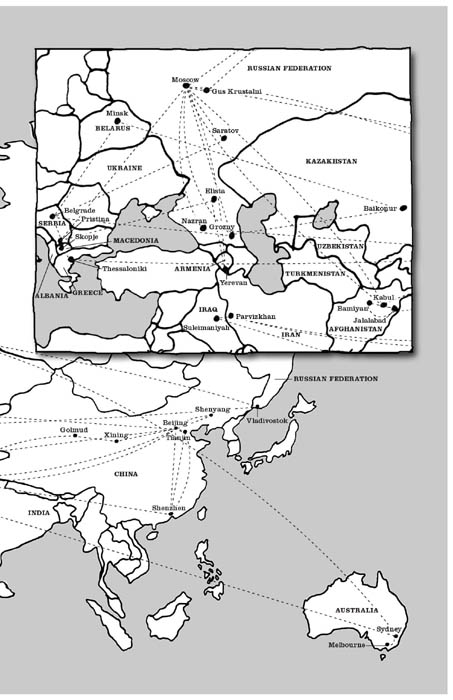

I had reported on conflicts from Chechnya to Kosovo to Afghanistan and never been hurt. They had shocked me and depressed me but they had also exhilarated me. Big stories, intense experiences, strange cultures, misadventures, physical danger, isolation, tension, fear; moving on, always moving on, had become my idea of what passed for a good life.

Now I could only wonder how I became this way and why I had chosen to live and work in a world that normal people tried to flee. I could only marvel that Id once thought covering wars would be fun.

Part One

EAST

Chapter 1

Sydney to Moscow, 1995

Leaving

Some people become television journalists to shine light in the darkness, making films to expose injustice and build understanding. More do it just for the money. Many see television as glamorous; a few hope it will make them famous. But to my knowledge, nobody ever became a television reporter to film caravan parks in East Gippsland.

It was just how things worked out for me.

In 1990, as the first Gulf War was about to get under way, I was working for a TV travel program, planning a shoot about budget holidays in Victoria. I had always had a vague plan to become a foreign correspondent, but some unwise career choices had trapped me in the dimmest recesses of Australian television.

When a revolution overthrew the dictator Ferdinand Marcos in the Philippines in 1986, I was comparing toasters for a consumer-affairs program. When the Berlin Wall came down three years later, I was profiling a stripper who also worked as a horse strapper