A ny Christmastime, at Harvard Universitys Sanders Theatre, in Cambridge, Massachusetts. The snow is deep outside. Into the cavernous, echoing lobby stream hundreds of families, all the generations mixed, coat-wrapped and scarf-wound, their breath clouding in the cold air. Christmas is in their heads, and this is a peak of it: their anticipated celebration, familiar as Mass to a Catholic or pantomime to an English child. The happy thunderous babel of voices washes over you like a sea.

The dragon with the big claws, says a very small boy insistently, will the dragon be there, like last year?

Betty! cries one harried mother to another, barely visible through the bobbing heads of her tribe. I never see you except at the Revels!

Wouldnt be Christmas without it.

Daddys going to sing the carols, says a small confident girl.

You sing, Ill listen, says her lugubrious father through his overcoat collar.

The lights go down, the voices hush, and the families are deep suddenly in reawakened echoes of winter festivals from two thousand years past: pagan and Christian, Celtic and Nordic, Anglo-Saxon and Hebrew, and a dozen other cultures. A clear solo voice sings the lilting Hebridean Christ Childs Lullaby; eerily horned dancers stalk through a fertility dance as old as Stonehenge; in a bright swirl of medieval costume, a procession of musicians and chorus sings its way through the house to the stage. The dragon duly cavorts; beribboned Morris men leap and dance; a troupe of players brings brave Sir Gawain to challenge the Green Knight. The audience roars, laughs, sings, and at last finds itself winding in an immense singing, dancing line through the crowded lobby, led by a smiling, dark-haired man whose voice rises strong over the rest:

Dance, then, wherever you may be,

I am the Lord of the Dance, said he...

And the lugubrious father is singing and dancing there too in the throng, overcoat flapping wide, a look of bemused delight on his face.

We stand, John Meredith Langstaff and I, in the dim-lit theater, among the empty seats, discussing a forthcoming spring production of the Revels. He waves at the air: I want a great forty-foot mast to go up, in Act One, right here. Men hoisting it, singing sea chanteys the way they were meant to be sung.

Thats lovely, but its crazy. Well hit that chandelier.

Theres some marvelous material windlass chanteys, chanteys for hoisting sail

Too dangerous. And what about the sight lines?

He says craftily, We could have the mast sway, in that storm at the end of your seal story. Wouldnt that be great?

It wont work, Jack. We might brain half the audience. Itll be too heavy. Too complicated. Too

Three months later, a thousand people cheer as a tall shining mast rises dramatically in the middle of Sanders Theatre, bringing timeworn sea chanteys vividly alive. When the artistic director of the Revels has dreams, they tend to come true....

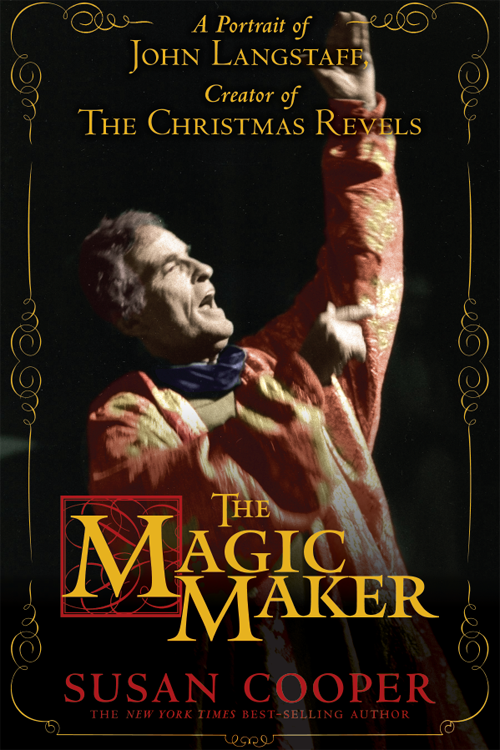

In the thirty years since I wrote those words in The Horn Book Magazine, John Langstaffs Revels has spread across the United States: its Christmas and spring or summer productions are a seasonal landmark not only in Cambridge but in Hanover, New Hampshire, in New York City, in Washington, D.C., in Oakland and Santa Barbara, California, in Houston, Texas, in Tacoma, Washington, in Portland, Oregon, and in Boulder, Colorado. It has spawned similar celebrations in many smaller towns, the range of outreach work is enormous, and the scope of the whole network continues to evolve under its new leaders. An idea has become an institution. The major beacons in all the arts depend not only on artists, performing or creative, but on Makers: charismatic visionaries like Joseph Papp, Jacques dAmboise, Tyrone Guthrie, Martha Graham and John Langstaff.

As you may know from experience, its hard to define the Revels. It is not commercial theater; it isnt folksy; it isnt a concert; it is neither religious nor pagan yet it combines certain strong elements from all these into a peculiar form of theatrical magic. The National Endowment for the Arts, giving Revels a grant in its early days, called it a new and different form of musical theater. Using a core of professionals and a chorus of amateur singers, Langstaff contrived to weave song, dance, and drama into a celebration of the winter solstice. He hit a nerve, providing an answer to that submerged yearning for ritual, and for the marking of ancient landmarks in human life, which lies very deep in all of us and which very little in the American Way can satisfy. (In Britain, that same yearning is probably the reason why the monarchy survives.) Telling signs of emotion have always appeared in letters from the fiercely possessive audiences who buy out every Revels production in every city: I cant remember the last time I felt such a personal involvement in a performance, ran one typical example. I left with an incredible glow of joy.

I am a writer, mostly of books published for children, though overall Im more of a GP than a specialist. I joined the Revels family in 1975, after being recruited by Jack (nobody ever called him John for more than five minutes) backstage at the previous years Christmas production. For the next twenty years I wrote verse, short plays, stories, lyrics, program notes, record notes, and any other words Jack felt he needed. We became working partners, linked by respect, understanding, and the pleasure of the job we were doing; we grew to know most of each others strengths, failings, and foibles, and when he died in 2005 I lost one of my three closest friends.

A year or so before that, after a series of tentative references to a project Id like to talk to you about, he had announced that he wanted to write a book that he thought would be called The Choirboy. Starting with that extraordinary childhood of mine, going away to choir school for years at the age of seven. Ive been thinking about it a lot so much that happened later must have been sparked back then.... Will you help me?

Of course, I said.

But time ran out on us. So Im doing it for him, using our notes, his papers, my own files and tapes, and some invaluable recordings made by the Revels Music Director, George Emlen, and its Marketing Director, Alan Casso. I owe particular gratitude not only to George and Alan but to Gayle Rich, to Nancy, Carol, Deborah, and David Langstaff, to Paddy Swanson, Brian Holmes, Sue Ladr, Roger Ide, David Coffin, Jerry Epstein, Jay OCallahan, and many others. This is not a full Langstaff biography, nor a history of the thriving, complex organization that Revels, Inc., has become today, but it shows, I hope, how Jack Langstaffs Revels began.

Here is a portrait of one of the Makers, and now and again a personal record of a working friendship.