The Editors of New Word City - Pope John Paul II

Here you can read online The Editors of New Word City - Pope John Paul II full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2013, publisher: New Word City, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Pope John Paul II

- Author:

- Publisher:New Word City

- Genre:

- Year:2013

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Pope John Paul II: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Pope John Paul II" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

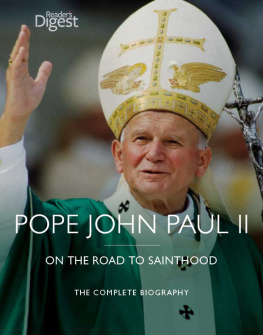

Pope John Paul II was a towering figure - a prime actor on the world political stage and a man who brought his church through a troubled time with his strength, charisma, and sense of mission. Its because of his leadership that the Catholic Church, though its rifts werent fully healed, grew in numbers and influence during his papacy. Here, in this short-form book, is his extraordinary story with lessons for leaders everywhere.

The Editors of New Word City: author's other books

Who wrote Pope John Paul II? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

Pope John Paul II — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Pope John Paul II" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Soon after the first puff of white smoke wafted from the Sistine Chapel chimney, it was plain to the world that Pope John Paul II would be a new kind of pontiff. His energy, sense of mission, canny use of power, and, above all, his charisma were a welcome contrast to the distant, inward-looking style of his predecessor, Pope Paul VI.

There was no surer token of change than the new popes introduction to the thousands of faithful waiting in Saint Peters Square to greet him after his election on October 16, 1978. Apart from insiders, few in the church had ever heard of Cardinal Karol Wojtyla, a Polish bishop, the first non-Italian to be raised to the papacy in more than four centuries. Even the prelate who introduced him, Cardinal Pericle Felici, stumbled over pronouncing his name - Voy-TEE-wa.

The stocky, robust, emotional new pope spoke into a murmuring hush. I have come from a faraway country, he said in fluent but lightly accented Italian. Far away but always so close in the communion of faith. The scattered applause grew louder. I do not know whether I can express myself in your - in our - Italian language, he said. Laughter erupted and turned into cheers. If I make mistakes, he added, his smile becoming a grin, you will correct me.

The cheers grew into an ovation at the mere thought of a pope who could be corrected, and then the crowd began chanting: Viva il Papa! Viva il Papa! Viva il Papa!

And that promise of warmth, humanity, and self-deprecation - a papacy rooted in Karol Wojtylas humble beginnings - was quickly made good. The new pope did away with many of the ceremonial frills that had long preoccupied the Vatican. He abandoned the traditional papal pronoun we for a direct I. Instead of a ceremonial triple-crown investiture, he celebrated an inaugural outdoor Mass for 100,000 of the faithful in Saint Peters Square. He laughed easily and heartily and enjoyed chatting. He wrote many of his own speeches and decrees in longhand. A lifelong athlete and outdoorsman, he built a swimming pool at his summer palace at Castel Gandolfo, triggering a spate of cartoons of the pope swimming with a miter on his head. And when a visiting prelate commented that the pool must have been expensive, John Paul retorted, Holding another conclave to elect a new pope would cost even more.

John Paul became the pilgrim pope, spending more than 10 percent of his pontificate away from the Vatican on more than 100 trips that would take him to 129 countries. His travels became an integral part of his legacy, inspiring and energizing untold millions of people who flocked to see him. His evangelism swelled membership in the Roman Catholic Church from 750 million to more than 1 billion.

John Paul was a tireless champion for human rights, peace, disarmament, and political freedom, as well as aid for poor people and developing nations. His political and moral backing helped overthrow the Communist government of Poland and contributed to the collapse of the Soviet Union. He led the ecumenical cause, reaching out with dramatic gestures to the Orthodox Church, to Anglicans and Lutherans, and even to Jews and Muslims. He consistently opposed capital punishment, preemptive war, and anti-Semitism, beginning in his native Poland.

But he was also a pope of tradition and authority, so much so that some in the church called him a throwback to the imperial papacy of the nineteenth century. If he entranced the world with the force of his personality, he was anything but a soft touch when it came to churchly matters. He insisted on rigorous discipline and obedience to traditional doctrines. He held that the liberal reforms of Pope John XXIIIs Vatican Council II had been hugely overdone and misinterpreted. He ruled out marriage for priests and would not even discuss ordination of women. He fought abortion, stem-cell research, euthanasia, all forms of artificial birth control, and gay marriage. And for all his own political activism, he banned priests from taking part in politics and cracked down on the leftist liberation theology of rebellious churchmen in Latin America.

The story of John Paul II is one of paradox and contradiction. The one theme that fits all his actions is his independence; like Frank Sinatra in vestments, the he did things his way. His obituary in the independent, liberal-leaning National Catholic Reporter concluded that he leaves behind the irony of a world more united because of his life and legacy, and a church more divided. But he was unquestionably an effective leader, one of the strongest of his time, and his life holds many lessons.

Karol Wojtylas childhood in Poland, and his survival under first the Nazis and then the communist government, are crucial to understanding his role as pope and leader. The Polish culture, strongly influenced by its history, language, and the Catholic faith, values intellectual and artistic achievement more than financial success. And the experience of two totalitarian regimes reinforced Wojtylas respect for liberation and freedom.

He was born on May 18, 1920, in the industrial town of Wadowice, near Krakow. His father, also named Karol, was an army officer. His mother, Emilia, was a schoolteacher. A brother, fourteen years older than young Karol, became a doctor but died of scarlet fever when Karol, known as Lolek, was only twelve, and the boy never knew his older sister, who died in infancy. Emilia was to die of heart failure when Lolek was just eight years old. Raised by his father, he went to public schools and became an athlete, skating, swimming, boating, and hiking in the Carpathian Mountains. He played ice hockey and, in a town with a heavily Jewish population, was the goalkeeper for a soccer team made up mostly of his Jewish schoolmates. But he was also a keen student, gifted in languages, and he wrote poetry and acted in plays. After the Nazi invasion in 1939, the theater was banned, but Wojtyla kept on acting in underground dramas in private homes for audiences of just twenty to thirty people.

The Nazis also closed the Jagiellonian University, where Wojtyla was enrolled as an undergraduate. He found a job as a laborer in a limestone quarry, which left its mark on his large, work-scarred hands. Later, he took a job in a chemical factory, helping his ailing, retired father make ends meet and providing himself a work card that sheltered him from deportation to a labor camp. But his father died of a heart attack in 1941, leaving him alone. At twenty, he was to say, I had already lost all the people I loved.

Wojtyla began thinking seriously about becoming a priest, and soon enrolled in the underground seminary being run by the now clandestine Jagiellonian University. He lived in the basement of the palace of his patron and mentor, Archbishop Adam Stefan Sapieha, until the end of the war. In effect, it was a kind of house arrest.

Wojtyla was ordained late in 1946, and, as the Communists consolidated their power in Poland, Archbishop Sapieha sent his protg to Rome to continue his studies. After earning a doctorate in philosophy, he went back to Poland, first as assistant in a village church and then to obtain a second doctorate and become a lecturer in social ethics at the Spiritual Seminary in Krakow. He was fast becoming known as an intellectual, and, after a series of rapid promotions, he became archbishop of Krakow in 1964. He was just forty-three years old. Three years later, Pope Paul VI made him a cardinal.

Wojtyla could multitask before the term was invented. Once, in a meeting led by the fearsome prelate Cardinal Stefan Wyszynski of Warsaw, the cardinal noticed Wojtyla reading in the back of the room and abruptly asked him to summarize what had been said. Wojtyla obliged, missing nothing. In addition to his studies and many scholarly essays, he wrote poetry under a pseudonym. At the Second Vatican Council in 1963, he gave a celebrated address on social philosophy and helped write two of the councils principal declarations, but he also wrote poems, later published, about the conclave.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Pope John Paul II»

Look at similar books to Pope John Paul II. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Pope John Paul II and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.