Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

Published by Basic Books, an imprint of Perseus Books, LLC, a subsidiary of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to www.hachettespeakersbureau.com or call (866) 376-6591.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

Print book interior design by Jack Lenzo.

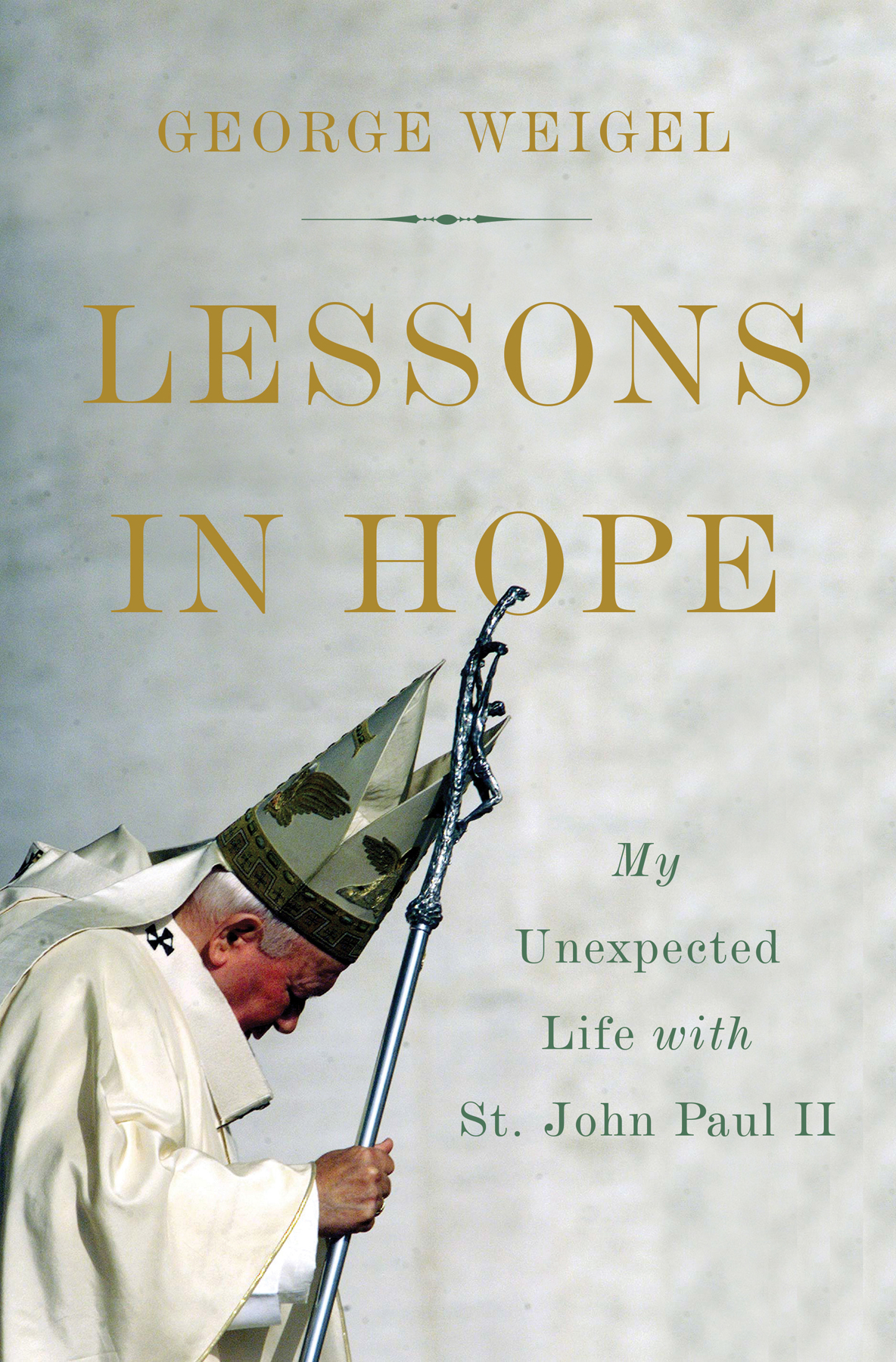

I N EARLY D ECEMBER 1995, I FLEW FROM W ASHINGTON TO R OME TO give the keynote address at an international conference on secularism and religious freedom. One of the oddities of European academic conferences is that the keynote address is sometimes the finale of the proceedings, so my paper was slotted at the end of a three-day meeting. This curiosity of scheduling set the table for something even stranger, however. For the chairman of the conferences closing session, Cardinal Agostino Casaroli, former secretary of state of the Holy See, devoted his remarks to a refutation of me and of the analysis of the Churchs role in the collapse of European communism I made in a 1992 book, The Final Revolution.

The cardinals suggestionthat I didnt quite understand Pope John Paul II and ought not be taken quite so seriously as an interpreter of the Popes thoughts and actionswas more than a little ironic. And the irony turned on a dinner conversation in the Vatican the night before, of which Cardinal Casaroli, the Popes first collaborator for more than a decade, was completely unaware.

The previous day, as the conferences postlunch session was about to begin, I had slipped into the back row of a large auditorium and sat down beside my friend Father Richard John Neuhaus. As was often the case, we were thinking the same thing: the moment called for a nice winters nap, our heads enclosed in earphones as if we were paying close attention to the simultaneous translation while several colleagues droned on. There would be no napping that day, however. For no sooner had I muted the earphones than a seminarian, somewhat excited, began tapping me vigorously on the shoulder. I looked around, removed the headset, and heard him say several times, Don Stanislao is on the telephone for you. He spoke in slightly awed tones, for my caller was Monsignor Stanisaw Dziwisz, John Paul IIs highly competent secretary and the man to whom few people in Rome wanted to say no.

I took the call and Dziwisz, as usual, got straight to the point: Come over for dinner tonight and bring Father Neuhaus with you. I returned to the auditorium, where Richard was fast asleep, and gave him a gentle nudge. When he came to, I leaned over and said, If your calendar permits, were dining with the Holy Father tonight. Richard allowed as how that might be fitted into his social schedule.

So at 7:15 that evening we presented ourselves at the Portone di Bronzo, the Bronze Doors of the Apostolic Palace, and were duly led to the Terza Loggia, the third floor, and the papal apartment. We waited a bit in one of the apartments small parlors, which, like the rest of the apartment, conjured up middle-class Italian family, not Borgia decadence. Then, without any ceremony, John Paul II and Msgr. Dziwisz came in, greeted us, and led us into the dining room, where Fr. Neuhaus and I were seated across from the Pope. John Paul said his usual rapid-fire Latin grace before meals and we tucked into an antipasto followed by roast chicken with a local red wine.

Conversations at John Paul IIs table typically covered a lot of territory. The Pope was insatiably curious and used his mealtimes to keep himself abreast of new arguments, new books, trends in the world Church, and people his guests thought he should meet. But the table talk seemed disjointed this time, as if the Popes mind were elsewhere. At one point, Fr. Neuhaus raised the issue of whether a thorough biography of the Pope wouldnt be a good idea and whether I should do itan idea I had broached with John Pauls press secretary, Joaqun Navarro-Valls, seven months before and had talked over with Richard more recently. The Pope immediately changed the subject, as if this were something he didnt want to discuss. So the conversation drifted into other matters, with John Paul looking into the distance from time to time as if pondering how to say something.

Then, completely out of the blue, the 263rd Successor of St. Peter abruptly and forcefully said to Fr. Neuhaus, while glancing at me, You must force him to do it! You must force him to do it! It, of course, was the biography, and him was me. Richard said that he didnt think that any force was going to be required. I simply exhaled. John Paul II smiled.

Later that night, after we had shared a scotch or two with Monsignor Timothy Dolan, the rector of the Pontifical North American College and our host during this Roman excursion, Richard said, You know, this is going to change your entire life. I told him I didnt think so; Id do the biography over the next few years and then return to the life I was leading at the Ethics and Public Policy Center, the Washington think tank that had been my professional home since 1989. No, Richard insisted, this is going to change everything.

He was right, if in that slightly exaggerated way that was one of his trademarks and one of his charms.

Becoming John Paul IIs biographer didnt change everything. But it did become the pivot of my life. I began to see a lot of what had gone before in a new perspective, and I gradually came to understand that I had taken on a responsibility that would define me in the future, in ways I could not have anticipated that December afternoon in Rome when a nap seemed in order.

This album of memories is one unanticipated consequence of that dinner and what flowed from it.

When the second volume of my John Paul II biography, The End and the Beginning, was published in 2010 and I was promoting the book in its various language editions, I discovered that what my audiences most wanted to hear were stories: stories about the man who had gone home to the Fathers house in 2005, stories that would make him present again by rekindling memories or illuminating previously unknown aspects of his rich personality. That yearning to get to know more personally a saint who bent the course of history in a humane direction, and to know him in ways that didnt quite fit the genre of serious biography, struck me as the impulse that inspired the informal lives of the saints over the centuries. Responding to that curiosity seemed another way to honor the pledge I made to John Paul II at the end of his life: that I would complete the task I accepted at his dinner table on December 6, 1995.

Doing so, however, requires widening the anecdotal lens and exploring how it was that someone who never expected to become a papal biographer became just that. When I finished