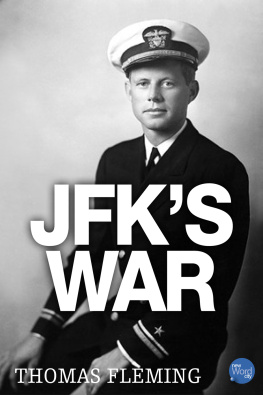

The most famous collision in U.S. Navy history occurred at about 2:30 A.M. on August 2, 1943, a hot, starless, moonless night in the Pacific. Motor Patrol Torpedo Boat109 was idling in Blackett Strait, a stretch of salt water off the South Pacific island of Kolombangara. Lieutenant (junior grade) John F. Kennedy, the commander of the eighty-foot-long craft, had orders to attack any and all Japanese destroyers or barges trying to resupply and reinforce Japanese soldiers stationed farther down The Slot, the long narrow ribbon of water that traversed the Solomon Islands. With virtually no warning a Japanese destroyer smashed into PT109, slicing it into two unequal parts, and igniting the thousands of gallons of high octane gasoline in PT109s tanks. The PTs commander and surviving crew were flung or leaped into the blazing water, beginning an ordeal that writers, relatives, and friends would use to create a drama that propelled John F. Kennedy to the presidency of the United States.

In the ensuing excitement, the rest of Kennedys naval career virtually vanished from sight. How the Japanese destroyer Amagiri was able to run down the smaller, far more maneuverable PT109 was never discussed. Totally ignored were the comments of several PT boat captains and the PT squadron commander that the disaster was Lieutenant Kennedys fault. Equally obscured was the profoundly human story of Jack Kennedys transformation from a cynical playboy to a grieving adult with a commitment to his country and his countrymen.

Perhaps the best kept secret was Kennedys fragile health. As one historian has put it, he was not qualified to get into the Sea Scouts, much less the U.S. Navy, especially with a war looming. From boyhood he had suffered from a variety of illnesses, including chronic colitis, scarlet fever, and several bouts of hepatitis. In 1940, he had volunteered for the U.S. Armys Officer Candidate School and had been rejected as 4F. The doctors cited a birth defect, an unstable back, which frequently gave him bouts of severe pain. Also noted were ulcers, asthma, and an unnamed form of venereal disease.

In the aftermath of PT109, Kennedys friends and crew attributed his back and stomach trouble to the violence of the collision and swallowing seawater mixed with gasoline in the ensuing chaos. In fact, Jack Kennedy got into the Navy only because his immensely wealthy father, Joseph P. Kennedy, persuaded Captain Alan Goodrich Kirk, head of the Office of Naval Intelligence, to let a Boston doctor certify his sons health in a private examination. Kirk had been the naval attach in London during the senior Kennedys ambassadorship to the Court of St. Jamess from 1938 to 1940.

Jack Kennedy was sworn in as an ensign on September 25, 1941. At twenty-four, he was already something of a celebrity. With considerable help from his father and New York Times columnist Arthur Krock, he had turned his 1939 senior thesis at Harvard into a book about the British failure to rearm for World War II - Why England Slept. Joe Kennedy had persuaded Time-Life publisher Henry Luce to write a foreword. Joe Kennedy financed a publicity campaign that made the book a bestseller.

Jack Kennedy was soon enjoying life as an intelligence officer in Washington, D.C. His twenty-one-year-old sister, Kathleen, was already there, working for the Washington Times-Herald, an isolationist anti-Roosevelt newspaper that harmonized nicely with Joe Kennedys political views. Kathleen introduced her brother to blonde, blue-eyed Inga Marie Arvad, a beautiful, Danish-born reporter who found his wealth, good looks, and effervescent Irish charm fascinating. Like the other Kennedy sons, Jack had long since decided to imitate his father, whose sexual adventures ranged from Boston to Hollywood. But sophisticated Inga, who at twenty-eight was already twice married and currently separated from Hungarian film director Paul Fejos, soon became much more than a casual fling. Many biographers call her the love of Jack Kennedys life.

Unfortunately, Inga had a problem that threatened to terminate the ensigns naval career. She had spent a great deal of time in Berlin as a reporter for various Danish newspapers and had grown friendly with Hermann Goering, Heinrich Himmler, and other prominent Nazis. She had even charmed Fuhrer Adolf, who declared her a perfect Nordic beauty. Almost as troubling was her recent liaison with pro-Nazi industrialist Axel Wenner-Gren, currently living in Mexico. No one paid much attention to this worrisome past until Japanese planes smashed up the Pacific fleet at Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, and Washington D.C. went on a war footing. Federal Bureau of Investigation chief J. Edgar Hoover and not a few other people, up to and including Franklin Roosevelt, took a dim view of a naval intelligence officer named Kennedy cohabiting with a suspected German spy. By this time, Jack Kennedy was calling Ms. Arvad Inga-Binga.

Soon Kathleen Kennedy was confiding to her boyfriend of the moment that her father had heard about Inga and was getting ready to drag up the big guns. For several torrid months Jack Kennedy defied a wrathful Joe Kennedy, Sr., while the Navy debated whether to cashier him. But when Inga started demanding a wedding ring, Jack reluctantly informed her that the affair was over.

The imbroglio left Kennedy depressed and exhausted. He told a friend he felt more scrawny and weak than usual. His lower back began giving him excruciating pain. He requested a ten-day leave so he could consult with his doctor at the Lahey Clinic in Boston. Two weeks later he asked for a six-month leave of absence for major surgery. Lahey doctors, as well as specialists at the Mayo Clinic, had diagnosed chronic recurrent dislocation of the right sacroiliac joint, which could only be cured by spinal fusion.

After two more months of pondering their patient in naval hospitals in Charleston and Boston, the physicians changed their collective minds and decided Kennedy did not need surgery. They incorrectly diagnosed his problem as muscle strain that could be treated with exercise and medications.

During Kennedys medical leave, the U.S. Navy won the battles of Midway and the Coral Sea. Ensign Kennedy emerged from his sickbed ferociously determined to see action. He persuaded his fathers old Wall Street crony, Undersecretary of the Navy James V. Forrestal, to get him into Midshipmans School at Northwestern University. He also visited Inga, who told a friend he walked like a limping monkey. At Northwestern Kennedy and 1,023 other would-be sea-going warriors plunged into a two-month course in navigation, gunnery, and strategy.

A pleasant interruption in their twelve-hour days was a visit from Lieutenant Commander John Duncan Bulkeley, the commander of the PT boats that had whisked General Douglas MacArthur and his wife and son from imminent capture by the victorious Japanese in the Philippines. This exploit earned Bulkeley a Medal of Honor and national fame in a bestselling book, They Were Expendable. In the struggle for the Philippines, Bulkeley claimed his PTs had sunk a Japanese cruiser, a troopship, and a plane tender and badly damaged another cruiser and a tanker. Not a word of that rodomontade was true. Bulkeley was now touring the country touting the PT as the key to victory in the Pacific. MacArthur, whose knowledge of naval warfare was minus zero, backed him with a call for 500 boats.

Bulkeleys oration inspired Jack Kennedy and every one of his classmates to volunteer for the PTs. A glance at Kennedys medical record would have disqualified him for command of a craft that threatened normal backs with dislocation. But Joe Kennedy had taken Commander Bulkeley to lunch a few weeks earlier and explained that he wanted Jack to get into the PTs to help him launch a political career after the war. Joe added that he hoped Bulkeley could assign him to duty that wasnt too deadly.

Next page