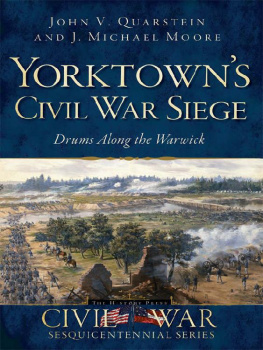

In the chill dawn of May 25, 1781, just outside the town of York, Pennsylvania, a bleary boy staggered from his tent and began to beat on the painted drum dangling from his left hip. From other tents on the sloping hillsides, soldiers stumbled out by the dozens, then hundreds. Some cursed the drummer, swearing it was not dawn yet; others cursed the sentry who awakened the drummer. In the Continental Army of the United States of America, dawn was considered the moment a sentry could see 1,000 yards - a judgment open to endless dispute. The cursing voices were an international mixture of American twang, German guttural, and Irish brogue.

Five minutes of groping for shoes woke the slow risers, and the red sun peered over the low hills. Company cooks went to work; the men crowded around the fires, watching the days bread being baked, complaining about the miserable food they had eaten yesterday. Officers warned everyone not to straggle - the brigade was to parade in an hour. When the drummer beat the signal to fall in, the men seized their muskets, cartridge boxes, and knapsacks and were ready for review by Brigadier General Anthony Wayne .

At thirty-six, Wayne had a reputation as a fighting general few could surpass. Called Mad Anthony by his men and The Modern Hero by fellow officers, he was famous for the fury with which he led his troops to the charge. His best-known exploit was the capture, with bayonet only, of the British fort at Stony Point on the Hudson in a night assault, but he had fought equally well in other battles. Discipline and courage were Waynes watchwords; at Stony Point, officers had orders to execute any soldier who showed cowardice. At the same time, Wayne had a genuine affection for his men and had been known to arrest and reprimand lieutenants who abused or struck a soldier.

Wayne had a special affection for the troops before him now, these men of the Pennsylvania Line, soldiers of his own state, who had followed him into the thunderous fog at Germantown to rout some of the best regiments in the British army, and slugged the same haughty professionals to an exhausted draw at Monmouth. Their uniforms were patched, ripped, threadbare, and many were without shoes, but they handled their guns with the assurance and pride of veterans. Even new recruits had profited from the weeks of drill and discipline Wayne had given them while waiting for the equipment, ammunition, and uniforms the Pennsylvania Assembly had promised but never delivered.

Now they could wait no longer. With or without shoes and new uniforms, they had to march. Grimly, knowing they would dislike the news, Wayne told them they were going south. Much as they hated the climate, they were in Virginia, where a British army was looting and burning its way through the richest American state, practically unopposed. Eventually, they might go even farther south, into the Carolinas and Georgia, where General Nathanael Greene commanded another tiny American army that was struggling to regain the three colonies recently ripped from the American union by George IIIs redcoats .

The war, which had begun as an impulsive, emotional revolt of a goaded people, had lasted a long time. Six years had turned stale the high talk about freedom and rights, and made even honest men wonder about the wisdom of generals who won one battle and lost two. Not victory, but The Victory, was what every man panted after now. The leaders knew it; Wayne, who was always close to his men, probably knew it better than anyone else. But the leaders knew something the average soldier could not know. Victory had never been closer. The enemy was as tired as they were. Struggling to control an immense sweep of continent, the British were even more vulnerable to a single decisive blow. Perhaps it could be struck in Virginia; it was easy for a general with Waynes ability to study a map and see how the British army marauding through the state could be pinned against the coast by a swift concentration of American strength. But any dreams of future glory in Waynes mind vanished with the reaction of his men to the news that they were marching south.

A barrage of shouts came from the packed companies: Dont march. We wont march until we get our money. Wheres the money you promised us? And the shoes? And the shirts? Dont march. We wont march. Not a man will march.

For a moment, Wayne stood frozen with horror. Despite the May sunshine, his thoughts were catapulted back to the nightmare of the previous January when the Pennsylvania Line erupted from their winter camp in Morristown, killed officers who resisted them, and began a march on Philadelphia, where they intended to settle their grievances with the Continental Congress at bayonet point. It was an event Americans had dreaded, and when it came, the Congress - and all of Philadelphia - was swept by wild panic. No one could deny the men had grievances. For three years, they had bled on a dozen battlefields and starved in such winter quarters as Valley Forge while their civilian compatriots dined in front of their warm fires. For this, they received $20 a month in collapsed Continental currency worth $1,200 to one dollar of hard money. Only Waynes cool courage had saved the Revolutionary Army from turning into an armed rabble. At the risk of their lives, he and Colonels Richard Butler and Walter Stewart stayed with the enraged troops for six days, and finally persuaded them to camp outside Princeton. There the president of the Pennsylvania Assembly, Joseph Reed , negotiated with a committee of sergeants, and gave them almost everything they demanded, including back pay, provisions, and the right to discharge, if they had served three years or more. Despite having to watch his beloved Line dissolve before his eyes, Wayne knew it was better than letting the soldiers dictate terms to the Congress itself - an example every other unit in the American army might have been tempted to follow.

A month later, Wayne had been ordered to York to recruit a new Pennsylvania Line. Amazingly, a large propor tion of the discharged men responded to their generals call while new recruits proved scarce. But old wounds were foolishly opened by Pennsylvanias state government, which casually promised the men that they would be paid in hard money - and then handed Wayne the worthless paper from the states own printing presses, which had less backing than Continental dollars. Even the bounties paid by enlistment auditors had depreciated to one-seventh of their nominal value. This was an alarming circumstance, Wayne admitted. The soldiery too keenly felt the imposition.

The citizens of York were no help. They refused to part with even a cup of milk for paper money and told the men they were fools to take it, and greater fools if they marched before receiving their due. Having successfully revolted once, the men saw no reason why they should not try it again. But this time Wayne was ready for them.

The moment the shouting began, he ordered them to their tents. Not a man moved. But now the general and his officers detected the leading mutineers, strategically placed on the right of each of the six regiments. Wayne snarled another order, and the officers rushed the men, knocked a few of them flat with the butts of their guns, and dragged the six ring - leaders in front of the brigade. Wayne ordered a court - martial on the spot.

While the appalled regiments watched, a board of officers was appointed, the charges were heard, and the men were condemned to death. Grimly, Wayne ordered men executed immediately. The particular messmates of the culprits were their executioners, Wayne reported. While the tears rolled down their cheeks in showers, they silently and faithfully obeyed their orders without a moments hesitation. One by one the men had handkerchiefs tied to cover their eyes, knelt on the ground, and the platoons marched up and fired a round into their backs.