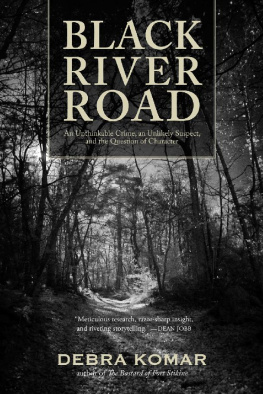

The Ballad of Jacob Peck

Copyright 2013 by Debra Komar.

All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or any retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the publisher or a licence from the Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency (Access Copyright). To contact Access Copyright, visit www.accesscopyright.ca or call 1-800-893-5777.

Edited by Barry Norris.

Cover image: Thomas Tolkien (http://thomastolkien.wordpress.com)

Cover design and page design by Chris Tompkins and Julie Scriver.

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Komar, Debra, 1965

The ballad of Jacob Peck [electronic resource] / Debra Komar.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

Electronic monograph issued in PDF format.

Also issued in print format.

ISBN 978-0-86492-766-8

1. Peck, Jacob. 2. Babcock, Amos. 3. Hall, Mercy.

4. Murder-New Brunswick-History-19th century.

5. Circuit riders-New Brunswick-Biography. I. Title.

HV6535.C32N42 2013 364.152'3097151 C2012-907146-3

Goose Lane Editions acknowledges the generous support of the Canada Council for the Arts, the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund (CBF), and the Government of New Brunswick through the Department of Tourism, Heritage, and Culture.

Goose Lane Editions

500 Beaverbrook Court, Suite 330

Fredericton, New Brunswick

CANADA E3B 5X4

www.gooselane.com

To Sarah Lathrop and Steph Davy-Jow,

true and wondrous friends,

for never once suggesting

that I keep my day job.

The Ballad of Jacob Peck

Amasa Babcock lived in a shack outside of Shediac, New Brunswick

He had a wife and nine children and a sister of melancholy disposition

She was not able to come to the table

Jacob Peck arrived in the cold winter of 1805

He was an expert crowd rouser, in an era of hellfire preachers

Hed whip you into a frenzy at his mad house revival parties

Jacob Peck, he put a rope around Babcocks neck

Put him in a trance, some kind of zombie romance

The hypnotic rant of a hellfire preacher

Hellfire, Hellfire

Babcock held up a handful of grain from his hand mill

Removed his boots and socks revealing

this is the bread of heaven, the stars are falling

The whole family went nuts as they backed up against the bench

Babcock drew a knife and sharpened it, set his strength to kill his sister with it

And in the bloody mayhem, everybody snapped to their senses

Babcock ended up in a Dorchester jail

He had nobody to defend him

And the jury found him guilty and the judge sentenced him to hang

There was no compensation for an innocent man

Jacob Peck, he put a rope around Babcocks neck

Put him in a trance, some kind of zombie romance

The hypnotic rant of a hellfire preacher

Hellfire, Hellfire

One more for the hangman

Gloves for the hangman

John Bottomley, 1992

Reprinted with permission

Contents

Preface

In limine

Errors and misconceptions abound in the historical record. Personal opinion, speculation, and literary devices are introduced as fact and, if left unchallenged, become an accepted part of a legend. Far more elusive in the annals of history are those occasions when such errors can be traced back to an identifiable source. Yet, in the case of a gruesome murder that rocked an isolated settlement on New Brunswicks eastern shore in 1805, it is possible to pinpoint exactly how later accounts became littered with a startling array of fallacious details. Like the now-discredited theory of a mitochondrial Eve, myths disguised as truths regarding the murder were all born of a single source: an 1898 magazine article that inadvertently spawned generations of mutant versions of the tale.

The article, entitled The Babcock Tragedy, was not the first public discourse of the case. Despite the sensational nature of the crime, its rural location and small English-speaking population allowed the story to escape the notice of all but one of the newspapers of the day. On June 26, 1805, the Royal Gazette published a brief summary of the murder trial, penned with bias by the prosecutor in the case in the years before salaried news reporters, such was the fashion.

For almost eighty years, the case received little attention outside the confines of the tiny hamlet and erstwhile crime scene. Then, in 1884, his talk revived interest in the case. In 1898, William Reynolds writing under the pseudonym Roslynde published his account of the tragedy in the inaugural issue of New Brunswick Magazine. The article was never externally vetted as Reynolds was also the magazines editor and publisher. Reynoldss retelling of the story was rife with errors from the name of the killer and other key players to the sequence of events surrounding the crime yet, for want of scrutiny, it somehow became gospel.

In the years that followed, every published account of the crime has relied on the New Brunswick magazine article as its primary (and, in most cases, sole) source of information. Protracted discussions of the murder have been featured in a number of historical works, including Lawrences posthumously published opus, The Judges of New Brunswick and Their Times (1915); A History of Shediac, New Brunswick by John Clarence Webster (1928); Fannie Chandler Bells A History of Old Shediac, New Brunswick (1937); G.A. Rawlyks Ravished by the Spirit (1984); and Running Far In: The Story of Shediac by John Belliveau (2003). The story has also received chapter-length treatments in popular crime anthologies, including B.J. Grants Six for the Hangman (1983) and Allison Finnamores East Coast Murders: Mysteries, Crimes and Scandals (2005), an account so bastardized it is best considered a work of fiction. In 1992 Canadian folksinger John Bottomley even set Grants version to music; the lyrics of his haunting ballad introduce this book.

Without exception, the errors contained in Reynoldss 1898 article were propagated in each new rendition. Worse still, many authors took it upon themselves to embellish the story, offering their own unique twists and revisions to the tale. Like a childs game of Telephone played across the decades, the original message has morphed with each retelling, leaving the end result unrecognizable from the archetype. A lone academic consideration of the story by Professor David Graham Bell appeared as an appendix in his 1984 edited volume, The Newlight Baptist Journals of James Manning and James Innis.oft-reported myth that one of the storys central characters the itinerant preacher, Jacob Peck was a Baptist, rather than a follower of the New Light movement. Though Bells treatment far exceeds all prior accounts in terms of accuracy, often citing original historical documents, it is not without errors, as he too falls prey to embracing Reynoldss 1898 account as a reliable source.

If Bells academic effort falls at one end of the credibility spectrum, with Reynolds and his followers occupying the middle ground, the lunatic fringe has laid claim to the far end, creating a Web-based fantasy realm populated by conspiracy theorists and ufologists. A particularly bizarre case in point: Paul Kimball, a filmmaker who argues that a series of loud noises heard during one of Pecks more boisterous revivals was, in fact, proof of extraterrestrial visitation. To his credit, Kimball at least cites an original source in his quest to transform Amos Babcock the ill-fated protagonist of the tragedy, convicted of butchering his sister from murderer to alien abductee, lending a thin veneer of integrity to an otherwise ludicrous enterprise.

Next page