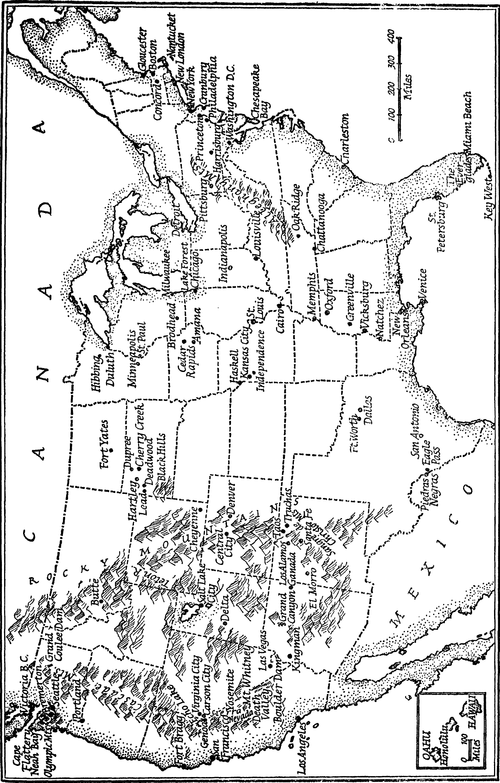

CoasttoCoast, my first book, was first published more than half a century ago. It is not long in geological terms, but it is quite a chunk in the life of a nation, and since 1956 the passage of history has transformed the subject of the work, America.

The United States has experienced such triumphs and such traumas since then, such colossal challenges, such tragic and marvellous adventures, such shifts of confidence and reputation, that it has virtually reinvented itself. It has sent its rockets to Mars and the Moon! It has been humiliated in war! It has been loved and loathed, admired, abhorred, envied and distrusted. And in the years after I wrote the book the USA became so incomparably rich and powerful that it was the only Great Power on earth.

None of this I foresaw when, in 1956, I ended a years travelling fellowship in the United States, and offered CoasttoCoast to my sponsors in lieu of the report I was obliged to present. I had come from a Britain that was still war-scarred, poverty-stricken and disillusioned. I found an America bursting with bright optimism, generous, unpretentious, proud of its recent victories, basking in universal popularity but still respectful of older cultures. I did not know it then, and nor did America, but chance had brought me across the Atlantic at the very apex of American happiness. I doubt if there has ever been a society, in the history of the world, more attractive than this republic in the decade after the Second World War.

Of course it had its downsides. Crime and corruption was rampant. Racism was ugly. The bigot Senator McCarthy was on the prowl. But it was a simple, innocent time for most Americans. Television was in its infancy, personal computers were inconceivable, McDonalds and Starbucks were unknown, drugs were hard to come by, and the same popular music had a guileless appeal for almost everybody the song Chattanooga Choo Choo was the theme tune, so to speak, of my introduction to the Great Republic.

Can you wonder that CoasttoCoast was written in enjoyment? That years wandering in America, in the prime of my youth, through a country so buoyant with success and generosity, was one of the very best presents of my whole life. I have been back there every year since, and if the United States of America is not always so beguiling today, is not always regarded around the world with the same grateful affection, nevertheless I love it still, and look back to my first journeys there as to a dream of young times and aspirations.

No matter that the America of this book exists no longer. In my mind its soul goes marching on!

Trefan, 2009

A t one time or another I have approached some splendid places, most of them distinct with mystery or age: Venice on a misty Spring morning, silent and shrouded, like a surrendered knight-at-arms; Moscow, its fortress barbarically gleaming; Everest, the watch-tower, on the theatrical frontiers of Nepal and Tibet; or Kerak of the Crusaders, high and solitary in the mountains of Moab. All are celebrated in history or romance; but none lingers so tenaciously in my memory as the approach to the City of New York, the noblest of the American symbols.

The approach from the sea is marvellous enough, but has become hackneyed from film and postcard. It is the road from inland that is exciting now, when Manhattan appears suddenly, a last outpost on the edge of the continent, and the charged atmosphere of the place spreads around it like ripples, and you enter it as you would plunge into a mountain stream in August. A splendid highway leads you there. It sweeps across the countryside masterfully, two white ribbons of concrete, aloof from the little villages and farms that lie outside its impetus, and along it the vehicles move in an endless, unbroken, unswerving stream. They carry the savour of distant places: cars from Georgia, with blossoms wilting in the back seat, or diesel trucks bringing steel pipes from Indiana; big black Cadillacs from Washington, and sometimes a gaudy convertible (like a distant hint of jazz) from New Orleans or California.

Through the pleasant country they pass, the traffic thickening as the big city draws nearer, and into the grimy industrial regions on its periphery; past oil refineries spouting smoke and flame, ships in dock and aircraft on the tarmac, railway lines and incinerators and dismal urban marshes; until suddenly in the distance there stand the skyscrapers, shimmering in the sun, like monuments in a more antique land.

A little drunk from the sight, you drive breathlessly into the great tunnel beneath the Hudson River, turning on as you do so the radio on your dashboard; the Lincoln Tunnel has its own radio station for the benefit of cars passing through it, and it seems churlish not to use it. You must not drive faster than 35 miles an hour in the tunnel, nor slower than 30, and there is an ominous-looking policeman half way along in a little glass cabin, so that you progress like something on an assembly line, soullessly; but when you emerge into the daylight, then a miracle occurs, a sort of daily renaissance, a flowering of the spirit. The cars and trucks and buses, no longer confined in channels, suddenly spring away in all directions with a burst of engines and a black cloud of exhausts. At once, instead of discipline, there is a profusion of enterprise. There are policemen shouting and gesticulating irritably; men pushing racks of summer frocks; trains rumbling along railway lines; great liners blowing their sirens; dowdy dark-haired women with shopping-bags, and men hurling imprecations out of taxi windows; shops with improbable Polish names, and huge racks of strange newspapers; bold colours and noises and indefinable smells; skinny cats and very old dustcarts; bus drivers with patient, weary faces. Almost before you know it, the mystique of Manhattan is all around you.

There is a richness to the life of this extraordinary island that springs only partly from its immeasurable wealth. A lavish fusion of races contributes to it, and a spirit of hope and open-heartedness that has survived from the days of free immigration. The Statue of Liberty, graphically described in one reference book as a substantial figure of a lady, is dwarfed by the magnificence of the skyline, and from the deck of a ship it is easy to miss it. But in New York, more than anywhere else in America, there is still dignity to the lines carved upon its plinth, and reproduced sixty years later at the airport of Idlewild:

Give me your tired, your poor,

Yourhuddledmassesyearningtobreathefree

Thewretchedrefuseofyourteemingshore.

Here in the space of a few square miles all the races mingle, and the extremes of human nature clash. This is not the ail-American city, but rather (as Lord Bryce remarked) a European city of no particular country; enlivened, sharpened and intensified by the American ideal.

Everyone has read of the magical glitter of this place; but until you have been there it is difficult to conceive of a city so sparkling that at any time Mr. Fred Astaire might quite reasonably come dancing his urbane way down Fifth Avenue. It is a marvellously exuberant city, even when the bitter winds of the fall howl through its canyons. The taxi-drivers talk long and fluently; not so well or so caustically as Cockney cabmen, but from a wider range of experience, for they may speak of a pogrom in old Russia, or of Ireland in its bad days, or speculate about the Naples their fathers came from. The waiters press you to eat more, you look so thin. The girl in the drug store asks pertly but very politely if she may borrow the comic section of your newspaper. On the skating rink at Rockefeller Center there is always something pleasant to see; pretty girls showing off their pirouettes; children staggering about in helpless paroxysms; an old eccentric sailing by with a look of profoundest contempt on his face; an elderly lady in tweeds excitedly arm-in-arm with an instructor.