APRIL

Hav Rig

AUGUST

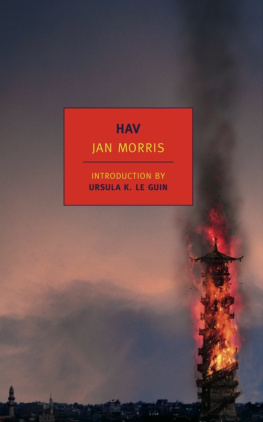

JAN MORRIS was born in 1926, is Anglo-Welsh, and lives in Wales. She has written some forty books, including the Pax Britannica trilogy about the British Empire; studies of Wales, Spain, Venice, Oxford, Manhattan, Sydney, Hong Kong, and Trieste; six volumes of collected travel essays; two memoirs; two capricious biographies; and a couple of novelsbut she defines her entire oeuvre as disguised autobiography. She is an honorary D.Litt. of the University of Wales and a Commander of the British Empire.

URSULA K. LE GUIN has published twenty-one novels as well as volumes of short stories, poems, essays, and works for children. Among her novels are The Left Hand of Darkness and The Dispossessed, both winners of the Nebula and Hugo awards.

Contents

THIS IS A NEW YORK REVIEW BOOK

PUBLISHED BY THE NEW YORK REVIEW OF BOOKS

435 Hudson Street, New York, NY 10014

www.nyrb.com

Copyright 2006 by Jan Morris

Introduction 2006 by Ursula K. Le Guin

All rights reserved.

Last Letters from Hav first published in 1985

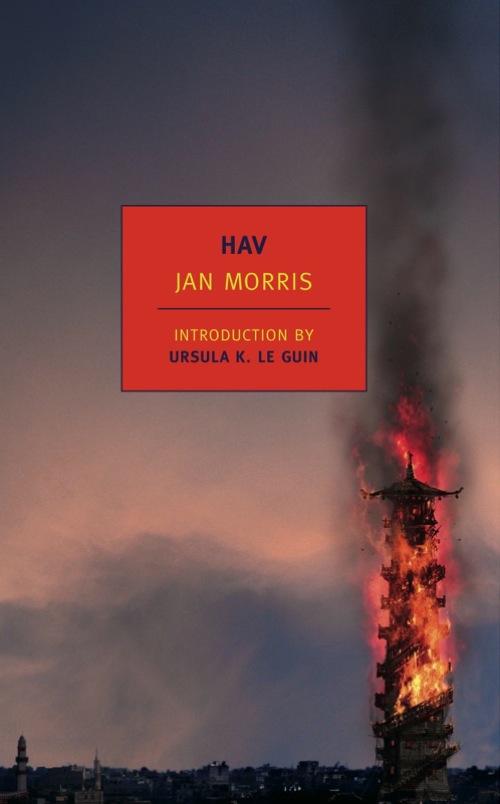

Cover image: Lee Gibbons

Cover design: Katy Homans

The Library of Congress has cataloged the earlier printing as follows:

Morris, Jan, 1926

Hav / by Jan Morris ; introduction by Ursula K. Le Guin.

p. cm. (New York Review Books classics)

ISBN 978-1-59017-449-4 (alk. paper)

1. TravelFiction. 2. Fantasy fiction. gsafd I. Title.

PR6063.O7489H39 2011

823'.914dc23 2011028970

eISBN 978-1-59017-470-8

v1.0

For a complete list of books in the NYRB Classics series, visit www.nyrb.com or write to:

Catalog Requests, NYRB, 435 Hudson Street, New York, NY 10014

But what if light and shade should be reversed?

If you press the switch then, will you turn the darkness on?

Avzar Melchik, Balilik (Dependence)

Epilogue

When the first part of this book, Last Letters, originally appeared in 1985, few readers apparently recognized it as fictional. They thought it described a real place, incomprehensibly little-known. They asked me how to get there. They wanted to know if one needed a visa. Even somebody at the Map Room of the Royal Geographical Society asked me to put him straight about Havs location. Only one single correspondent, an octogenarian lady in Iowa, saw my little book as allegory.

But hazy allegory it was meant to be, dressed up as entertainment. After forty odd years of wandering the world and writing about it, I had come to realize that I really seldom knew what I was writing about. I did not truly understand the multitudinous forces political, economic, historical, social, moral, mythical that worked away beneath the forces of all societies. I blundered around the planet, groping for meanings but not often absolutely understanding them, and working only with an artists often misguided intuition.

At the same time to be fair to myself societies themselves were becoming ever more complex and obfuscatory. Perhaps nobody could understand them properly, entangled as they were in the welter of new ideas, technologies, doubts and loyalties that seemed to be falling upon all with ever-increasing stress and energy. There was something ominously opaque in the air of the world, I thought.

So, having failed to master so many real places, I invented one to emblemize this new confusion of the peoples, this developing uncertainty about everything. I claim no prescience, but the brooding sense of foreboding I had sensed erupted into catastrophe on September 11, 2001, and so a still more bewildering zeitgeist was born.

This is the time-spirit of my books second part. It is allegorical again, but in a different kind. The confusions of the old Hav were rooted in history. Overlappings of ancient cultures had given the place its complexity, together with the influences and incursions of many centuries, and the responses of travellers down many generations. It was a jumble, but a jumble in which I was able to discern familiar signposts, events, notions and even personalities: and I might indeed have been able to make some sense of it all, were it not for the abrupt denouement of the Intervention.

The enigmas of Hav have remained into the years of the Myrmidons, into the second part of my book, but they are transmuted. History indeed still plays a part, but now the conflicts between contemporary truths muddy the waters more, and the striving for authenticities, and global corruptions, and resentments stemming not from the distant past, but from contemporary events. Fundamentalist religions confuse issues in Hav as everywhere else. Hints of terrorist subversion, and the threat of alien intervention, give added pungency to Havs peculiar kind of independence.

A whole world, indeed, has come into being since I wrote Last Letters from Hav. New states have emerged, and new kinds of cities suddenly erupted. At the back of my mind when I first contemplated the city-state of Hav were places like Trieste, Danzig or Beirut whose characters had been formed by the long processes of history. Twenty years later sudden new civic prodigies offered analogies startling conurbations, in desert or tropic, hitherto inconceivable and themselves all but fictional still.

So is there one essential allegory of Hav, in both its incarnations? I really dont know myself, and the second half of my book ends even more inconclusively than the first. Just as I wrote into the narrative my own meanings, bred by experience out of instinct, so I can only leave it to my readers, apologetically, to decide for themselves what its all about.

Novels arise out of the shortcomings of history.

Novalis (17721801)

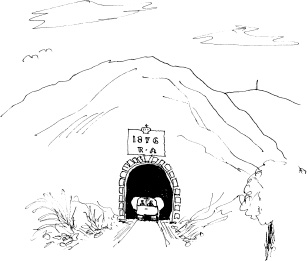

FRIDAY

Into the tunnel

Introduction

When Last Letters from Hav was published (and short-listed for the Booker Prize) in 1985, Jan Morriss well-deserved fame as a travel writer, and the unfamiliarity of many modern readers with the nature of fiction, caused unexpected dismay among travel agents. Their clients demanded to know why they couldnt book a cheap flight to Hav. The problem, of course, was not the destination but the place of origin. You couldnt get there, in fact, from London or Moscow; but from Ruritania, or Orsinia, or the Invisible Cities, it was simply a matter of finding the right train.

Now, after twenty years, Morris has returned to Hav, and enhanced, deepened, and marvelously perplexed her guidebook by the addition of a final section called Hav of the Myrmidons. To say that the result isnt what the common reader expects of a novel is not to question its fictionality, which is absolute, or the authors imagination, which is vivid and exact.

The story is episodic, entirely lacking in action or plot of the usual sort; but these supposed narrative necessities are fully replaced by the powerful and gathering direction or intention of the book as a whole. It lacks another supposed necessity of the novel: characters who, while they may represent an abstraction, also take on a memorable existence of their own. Like any good travel writer, Morris talks to interesting people and reports the conversations. And people we met in the first part of the book turn up in the second part to take us about and exhibit in person what has happened to their country; but I confess I barely remembered their names when I met them again. Morriss gift is not portraiture, and her people are memorable not as individuals but as exemplary Havians.