This book is dedicated to John

First published in Great Britain in 2006 by

Pen & Sword Military

an imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire

S70 2AS

Copyright M J Trow 2006

ISBN 1-84415-378-9

978-1-84415-378-7

ISBN 978-1-84468-365-9 (ebook)

The right of M J Trow to be identified as Author of the Work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Typeset in 11/13pt Plantin by Mac Style, Nafferton, E. Yorkshire Printed and bound in England by CPI UK

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the Imprints of Pen & Sword Aviation, Pen & Sword Maritime, Pen & Sword Military, Wharncliffe Local History, Pen & Sword Select, Pen and Sword Military Classics and Leo Cooper.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles, please contact

Pen & Sword Books Limited

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail: enquiries@pen-and-sword.co.uk

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

Contents

(between pages 88 and 89)

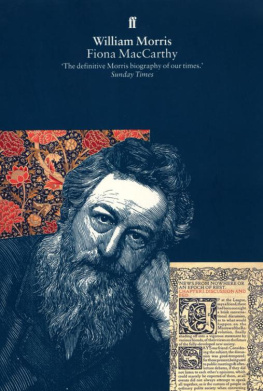

The only known photograph of Morris, probably taken at home, either in 1848 or in 1855.

Anonymous painting of Morris, probably painted before he left the 16th Lancers in 1847.

The church of St Michaels, Sandhurst, where Morris married Amelia Taylor in April 1852.

The various awards, medals and decorations which Morris acquired during his service in India and the Crimea.

Lord Raglans headquarters at Khutor-Karagatch, drawn by William Simpson.

Lord Cardigan.

Captain Louis Nolan.

Lord Lucan.

Lord Raglan.

A panoramic view of the Charge, as recorded by William Simpson.

The climax of the Charge, as portrayed by Christopher Clark.

The aftermath of the Charge, by Caton Woodville.

The sword presented to William Morris at Great Torrington, Devon, in 1856, with detail of the inscription.

The Casual and Squad Roll Book of Captain Morris, 17th Lancers.

Pages from the Squad Book, showing details of some of the men who rode behind Morris in the Charge of the Light Brigade.

The monument erected in 1860 in memory of William Morris on Hatherleigh Moor, North Devon.

The bas-relief of Morris being carried semi-conscious from the Valley of Death by Surgeon James Mouat and men of the 17th Lancers.

The Charge of the Light Brigade

There had been rumours about a film, following the events of the Crimean War far more closely than Errol Flynns epic of 1936, throughout the 1960s. At one point, it was to star Laurence Harvey and be called, after Tennyson and Mrs Woodham-Smith, The Reason Why. The first script was by John Osborne working in collaboration with director Tony Richardson and the redoubtable Mollo family as military/historical advisers. The Mollos set up the Historical Research Unit in 1964 and produced a fascinating collection of archive work on the uniforms of the period. The result was my favourite historical film, a Woodfall/United Artists Release, in 1968. Trevor Howard played Lord Cardigan, John Geilgud Raglan, David Hemmings Captain Nolan and Vanessa Redgrave Clarissa [sic] Morris.

The film is a wonderful evocation of the 1850s, contrasting the class-obsessed dilettante life of officers and their ladies with the grim squalor of other ranks and their women. The hero of Richardsons Charge is Louis Nolan, for reasons of simplicity and storyline gazetted to the 11th Hussars (he actually served in the 15th) at the start of the film. Before joining, he meets again his old Indian Army chum, William Morris (played by Mark Burns) and his soon-to-be-bride, Clarissa.

There has never been a film which so accurately captures the life of a regiment. The late Norman Rossington is quite superb as RSM Corbett, filling the heads of raw recruits with stirring tales of his regiments history, teaching them left from right and being broken to the ranks for refusing to obey Cardigans orders to spy on fellow officers. The quiet dignity he displays as the farriers cats bite into his torn flesh during a flogging in the riding school speaks for the thousands of men who really suffered that way.

And the screenplay by Charles Wood (who took over from Osborne) sums up the mental mind-set of the officer class. Nolan is appalled that floggings are standard practice and Riding Master Mogg (Alan Dobie) rounds on him with Would you have them fight like fiends of Hell for money? Or ideas? That would be unchristian.

Nolan soon falls foul of the petulant, impossible Cardigan, who despises the man as an Indian officer, one of that band who was professional and had seen action. The only action Cardigan witnessed before the Crimea was on manoeuvres at Chobham Ridges.

The Charge itself is a very small part of the film, perhaps fifteen minutes in its entirety; and the end by contrast to the patriotic, flag-waving beginning is brutish and almost silent; the drone of flies buzzing around the smashed corpses of horses and men.

Despite the meticulous planning of John Mollo, Richardson insisted on equipping the entire Light Brigade (and not merely the 11th Hussars) in crimson overalls. Conversely, the scarlet-jacketed Heavy Brigade wore a uniform of light cavalry blue. Theirs, as Richardson and Tennyson might have chorused, not to reason why.

Historical accuracy was sacrificed elsewhere. Thus Captain Henry Duberly, who was in fact Paymaster of the 8th Hussars, becomes a friend of Nolans in the 11th, and his wife, Fanny, whose journal is often quoted in this book, has a quirky, not to say kinky seduction scene with Cardigan on board his yacht! Crucially to the Morris mnage, Amelia had to become Clarissa, as screenwriter Charles Wood admitted to me, so that she could have an affair with Nolan and thus create some love interest. An old uncle of Monty Morris of Johannesburg (whose document collection forms the core of this book), on seeing the film in South Africa was so outraged at this that he leapt to his feet shouting Bloody rubbish! and had to be reminded it was only a story!

Such liberties did not detract, however, from a fine film. Who can forget the bristling lion that is Britain in the Punch-style cartoons of animator David Williams, furious at the cruelty of the Russian bear to defenceless Turkey, feathers flying in all directions? Or the grey faces of the cholera-struck army marching out from Varna and writhing in the agony of their vomiting under a merciless sun? Or the look of horror and disbelief on the faces of Raglan and his staff as the Light Brigade moves off down the valley of death?

The film was not a box-office success and Charles Woods deliberately stilted dialogue jarred a little, but today it has taken its place among the truly great achievements of the cinema, echoing perhaps our emotive response to the events it was portraying.

Richardsons targets were the nest of noodles, the officer class whose amateurish attempts to cope with warfare would lead to disaster. But he himself was a Communist and bisexual neither facet tending to acceptance anywhere at the time outside the traditionally bizarre world of films.