The Trial of

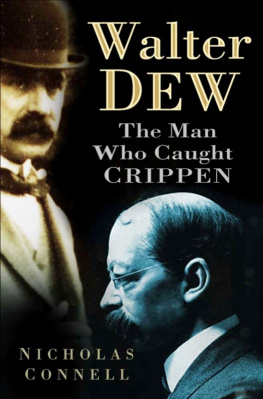

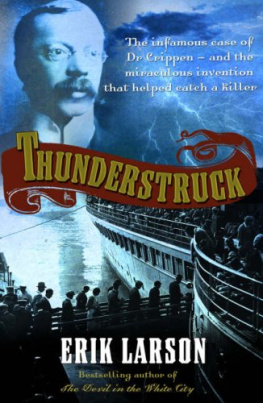

Hawley Harvey Crippen

EDITED

WITH NOTES AND AN INTRODUCTION

BY

FILSON YOUNG

TO

SIR BASIL HOME THOMSON, C.B.

IN RESPECT FOR HIS WORK

AND IN

FRIENDSHIP FOR HIMSELF

Contents

I.

Most of the interest and part of the terror of great crime are due not to what is abnormal, but to what is normal in it; what we have in common with the criminal, rather than that subtle insanity which differentiates him from us, is what makes us view with so lively an interest a fellow-being who has wandered into these tragic and fatal fields. A mean crime, like that of the brute who knocks an old woman on the head for the sake of the few shillings in her store, has a mean motive; a great crime, like that of the man who murders his wife and little children and commits suicide because he can see only starvation and misery before them, gathers desperately into itself in one wild protest against destiny what is left of nobility and greatness in the mans nature. It is not that his crime has any more legal justification than that of the murdering robber; it has not. On the contrary, it is more of an outrage upon life, and far more damaging in its results upon the community. Yet we do not hate or execrate the author; we profoundly pity him; it is even possible sometimes to recognise a certain terrible beauty in the motive that made him thus make a complete sweep of his little world when it could no longer cope with the great world. There are, at the least, reasons for a great crime; for a mean one there are, at the most, excuses. The region of human morality is not a flat plain; there are hills and valleys in it, deep levels and high levels; there are also certain wild, isolated crags, terrible in their desolation, wrapped in storms and glooms, upon which, nevertheless, a slant of sunshine will sometimes fall, and reveal the wild flowers and jewelled mosses that hide in their awful clefts.

Somewhere between these extremes, far below the highest, but far above the lowest, lies the case of Dr. Crippen, who killed his wife in order to give his life to the woman he loved. His was that rare thing in English annals, a crime passionel. True, the author of it was an American, and the victim a German-Russian-Polish-American, but the theatre and setting were those of the most commonplace and humdrum region of London life, and all the circumstances that contributed to its interest were such as are witnessed by thousands of people every day. The trial that followed it is in no sense remarkable from a legal point of view, except possibly with regard to the medical evidence; its chief interest lies in the story itself, in the characters of the people concerned, and in the dramatic flight and arrest at sea of Crippen and his mistress.

II.

In the year 1900 there came to London an entirely unremarkable little man, describing himself as an American doctor, to find some place in that large industry that lies on the borderland between genuine healing and the commercial exploitation of the modern human passion for swallowing medicine. This was Dr. Hawley Harvey Crippen, a native of Coldwater, Michigan, where he had been born in the year 1862, his father being a dry goods merchant of that place. It was not his first visit to England; he had previously been here in the year 1883, when at the age of twenty-one he had come to pick up some medical training. His education had followed the ordinary course of studies for the medical profession in America. After receiving a general education at the California University, Michigan, he proceeded to the Hospital College of Cleveland, Ohio. After a little desultory attendance at various London hospitals in 1883, Dr. Crippen had returned to New York, where in 1885 he took a diploma as an ear and eye specialist at the Ophthalmic Hospital there. He afterwards practised at Detroit for two years, at Santiago for two years, at Salt Lake City, at New York, St. Louis, Philadelphia, and Toronto. These movements covered twelve years, from 1885 to 1896.

In 1887 he had married at Santiago his first wife, Charlotte Bell; the following year was born a son, Otto Hawley Crippen, who at the time of the trial was living at Los Angeles. In the year 1890 or 1891 his wife died at Salt Lake City; and from there he returned to New York, where two years later he made the acquaintance of a girl of seventeen, whom he knew as Cora Turner. He fell in love with her, and although at the time he met her she was living as the mistress of another man, he married her and took her with him to St. Louis, where he had an appointment as consulting physician to an optician. He had found out that his wifes real name had not been Cora Turner at all, but Kunigunde Mackamotzki, and that her father was a Russian Pole and her mother a German.

Mrs. Crippen was the possessor of a singing voice, small but of a clear quality, her friends appreciation of which led her to entertain ambitions with regard to it which afterwards did not turn out to have been justified. Crippen, however, who was nothing if not an indulgent husband, allowed her to have it trained. This was in the year 1899, when they were living in Philadelphia; but Crippen allowed his wife to stay in New York for the purpose of having lessons, for which, of course, he paid, her ambition being that she should be trained for grand opera. She was still there when in 1900 Dr. Crippen came to London as manager for Munyons advertising business in patent medicines, the offices of which were at that time in Shaftesbury Avenue. About four months later he was joined by his wife, who had given up her lessons in New York and abandoned the idea of going into grand opera. Her ambitions now lay in the direction of the music hall stage, and she probably regarded England as a promising field for the development of her talents in that direction.

This part of the story may be very briefly dismissed. Although she came over with a sketch of her own design, and many obliging music hall agents undertook to float her in this country, nothing ever came of it save profit to the agents. Her musical sketch turned out to be a thing of which the music and the words both remained yet to be written, and competent artists were hired by the obliging agents to fill these omissions. Mrs. Crippen, who was assiduous in fulfilling all the external conditions of her proposed career, took a stage name of Belle Elmore, and provided herself with a quantity of dazzling dressesall, of course, at her good-natured husbands expense. But in fact the only attributes of the music hall artiste to which she ever attained were the stage name and the dresses. From star appearances in a first-rate London music hall her ambitions dwindled down to appearances of any kind at any music hall; and even these, when it came to the point, proved beyond the powers of the agents to secure. One or two feeble appearances were made at very minor music halls; but Mrs. Crippens talents were so inadequate, and the failure was so obvious, that even these attempts (for which, of course, Dr. Crippen had to pay) were abandoned. The truth was that Mrs. Crippen never had any talent whatever for the stagenot even the very moderate kind that will suffice to make the performance of an attractive young woman with a voice, wearing pretty clothes, and with some financial backing, acceptable to a music hall audience. Poor Mrs. Crippen had to content herself with frequenting music hall circles, reading the Era, retaining her stage name of Belle Elmore, and adding to her already large stock of theatrical garments. Here was, indeed, a small tragedy. If the poor woman had had any kind of talent, and had really been the music hall favourite that she loved to imagine herself, both she and her husband would probably be living now, each happy in a different sphere; but apparently she had nothing but vanity, no scrap of the ability or industry necessary even for her small purposes. The humblest English music hall has its standards; and Belle Elmore, in spite of her personal attractions and her pretty clothes, could not attain to them.

Next page