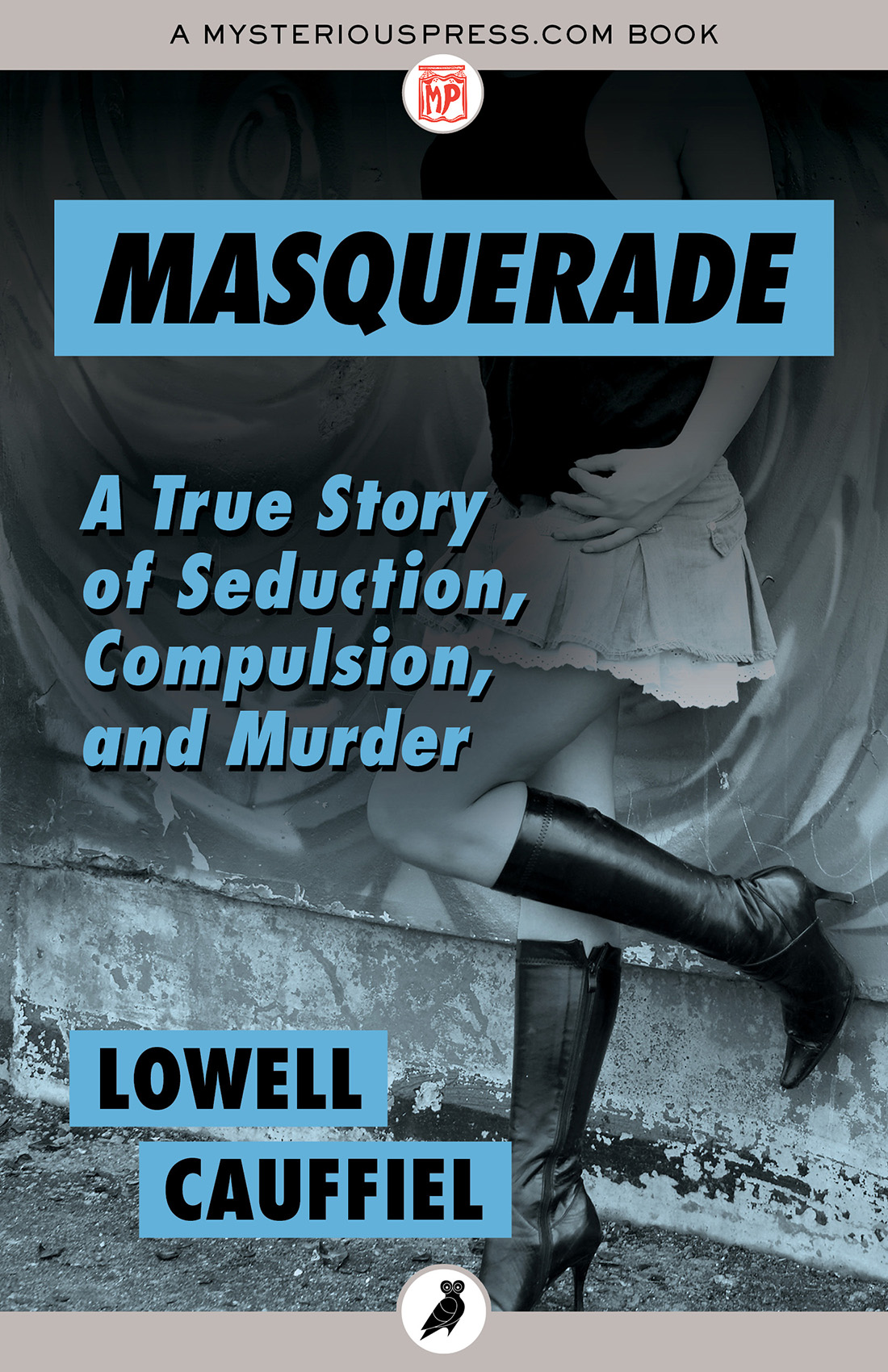

MASQUERADE

A True Story of Seduction, Compulsion, and Murder

Lowell Cauffiel

FOR MY FATHER AND MOTHER

Are we really happy here with this lonely game were playing?

Looking for words to say.

Searching but not finding understanding anywhere,

Were lost in a masquerade.

This Masquerade by L EON R USSELL

Nothing is at last sacred but the integrity of your own mind. Abide in the simple and noble regions of thine own life. Trust thyself. To believe in your own thoughts, to believe that what is true for you in your own private heart is true for all men; that is Genius.

Preface to Principles of Counseling and Psychotherapy

by W. A LAN C ANTY

Its almost irresistible. Shes so deliciously lowso horribly dirty!

Professor Higgins to Pickering in My Fair Lady

Prologue

We were jammed into the jury box, waiting for the first witness, when the main door of the courtroom swung open and the widow made her way toward the bench. More than a dozen reporters and artists filled the enclosure for the preliminary exam, simply because there was no other place to sit.

She wore a smart blue suit and medium heels, with her shiny hair pulled up in a french twist. Her eyes were swollen, her attractive face fatigued, but she marched up the aisle between the rows of spectators as though all of hell wasnt going to stop her.

Her name was Jan Canty, a Ph.D., psychologist, and marriage counselor, and wife of W. Alan Canty, Ph.D., psychologist, and murder victim. As she headed to the front of the courtroom, it occurred to a number of us that this had been a week quite unlike any other, even for a town numbed by six hundred homicides a year.

The headlines had progressed from PSYCHOLOGIST DISAPPEARS AFTER LEAVING OFFICE to POLICE THINK THEYVE GOT CANTYS BODY to BODY PARTS FOUND ON I-75 to TORSO FOUND MAY BE PSYCHOLOGISTS . There were reports as well of more body parts found buried in an animal boneyard 250 miles to the north, near the tourist town of Petoskey, Michigan.

The suspects facing preliminary examination on murder and mutilation charges were a young street whore named Dawn Marie Spens and her pimp, John Carl Fry, an ex-con known on the streets as Lucky.

Spens, once an honor student from the suburb of Harper Woods, sat sleepy-eyed at the defense table. She wore ragged jeans, a tattered baby blue blouse, and a pair of cheap black high heels with mesh toes. Fry relaxed at her side, his body weight shifted to one elbow. His white head was shaved, his mustache chiseled. His thick arms and barrel chest were like those of a professional wrestler.

Police still hadnt found all of Alan Canty, but the reporters in the jury box were just beginning to put the story together. There was talk in Homicide that the psychologist was the prostitutes regular customer, though the proposition seemed unlikely under the courtrooms bright lights.

Jesus, shes nothing, one reporter whispered, eyeing Spens. Maybe shes a terror in bed.

There was speculation that Canty had spent $140,000 on the girl over eighteen months, and there were reports that hed fashioned a second identity for himself as well. In the tough sections of the citys smoggy south side he had taken on another name and was known as a general practitioner.

It seemed an unlikely role for the fifty-one-year-old psychologist. His mother was a former president of the Detroit school board and a longtime leader of the PTA. His late father was a nationally known criminologist and a former executive director of the psychiatric clinic serving the citys largest court.

Some of us in the jury box already had portrayed the victim as an author, a teacher, and an expert on autism. He was a prominent professional with a flourishing practice in the Fisher Building, one of the citys most impressive office addresses.

When the first witness sat down, her back was erect. Jan Canty was only six feet from us on the stand. Yes, she knew the victim. Yes, they were married nearly eleven years. Yes, the last she heard from him, he was on his way home from the office, planning to stop at a grocery store for coffee.

No, she hadnt given anyone permission to dissect her husbands body.

There was nothing more about their life together, only answers that shored up the prosecutors charge of mutilation. We all wondered what she knew, but she left as quickly as she came.

Then a homicide cop began bringing forth witnesses through a door behind the bench. Soon it was clear why Jan Canty had waited outside, instead of with the others in the witness room. The proceeding took on a cinematic quality, the homicide cop a casting director as the standing-room-only audience murmured with each new character.

Visually, they all were striking. An unshaven southsider lumbered forward to testify in yellowed jeans and a faded black T-shirt. Another wore a gold earring, his arm tattooed with dragons and assorted slogans. A neighbor of the suspects raised his hand to be sworn, displaying a scorpion tattooed across his middle finger. One young blonde looked innocent enough with her turned-up nose and tiny frame. Then everyone saw the blue tattoo scrawled across her right triceps. Another waddled to the stand looking as though she was going to deliver any day. She was an odd sightso pregnant, but so close to such murder and mayhem.

They all seemed incapable of sharing anything in the life of the first witness of the day.

When the exam was over, I left the Frank Murphy Hall of Justice and decided to drive from downtown to take a look at the victims home in Grosse Pointe Park. Already I suspected that even a lengthy magazine story wasnt going to cover the distance between the two sets of images I saw in the court.

The drive out Jefferson Avenue along the Detroit River was stratified like a sociological core sample of class variations.

Once lined with ma-and-pa stores and thriving industrial plants, Jefferson was a broken chain of boarded building fronts and party stores fortified by bulletproof glass. A stretch of stylish high rises still stood, but only a few blocks away were some of the most economically depressed neighborhoods in the United States.

They werent much different than the streets that had produced the group of witnesses in court. Nobody in sight resembled the billboard over one burned-out building: a man in a designer tuxedo, savoring a snifter of Martell cognac.

Then, at Alter Road, Jefferson Avenue became the gateway to the PointesGrosse Pointe, Grosse Pointe Park, Grosse Pointe Farms, Grosse Pointe Woods, and Grosse Point Shores. Since the nineteenth century, these suburbs have been the home of the Motor Citys industrial aristocracy.

Old rail and auto money developed the most affluent sectionspeople with such names as Ford, Fisher, and Dodge. Some exceeded extravagance. Anna Dodge, wife of auto pioneer Horace Dodge, imported European craftsmen to build Rose Terrace, her monument to eighteenth-century French architecture. It was razed a few years back, but most of the other stone-walled estates remained along the shores of Lake St. Clair.

For years the Grosse Pointers took the term exclusive literally. Until a 1960 lawsuit, the suburbs were known for their point system, a checklist used by realtors to weed out prospective buyers. They awarded points on the basis of ethnic background, complexion, religious affiliation, and other such values.

That day I drove out Jefferson, the contrast was most dramatic at the foot of Alter Road, the boundary between Detroit and Grosse Pointe Park.