For Anne

Any attempt at a bibliography for this book would result in a very unwieldy list of publications, but I would like to extend thanks to the team of experts and friends who have made suggestions for subjects and cases to research and include, helped check facts and endured my obsession with the strange and the obscure: Stewart P. Evans and his good lady, Rosie, Andrew Selwyn-Crome, James Nice, Martin Sercombe, Britta Pollmuller, Martin and Pip Faulks, Rebecca Matthews, Fergus and Anne Roy, Ian Pycroft, Dr Geoffrey Clayton, Dr Vic Morgan, Michael Bean, Lynsey Frary, Helen Radlett, Michelle Bullivant, Steve and Eve Bacon, Christine and David Parmenter, Neil Bell, Lindsay Siviter, The Galleries of Justice in Nottingham, Thames Valley Police Museum, Lincoln Castle, Norfolk Police Archive, The Library of the University of East Anglia, my darling Molly and son Lawrence.

CONTENTS

The cases of murder spattered across the pages of history provide a dark mirror for so many aspects of the less seemly world of the past. Tales of the ultimate crime often live on in the stories told about a locality or even murders that became notorious to the whole nation, even infamous across the world; they can even be popular in the memory of generations to come after the event. Unfortunately, the re-telling and the frailties of the human memory have often meant the facts of cases the names of those involved, number of victims, or events surrounding the crime have been distorted, confused or simply forgotten.

This book does not attempt to list every infamous murder, nor does it pretend to be a concise almanac of such crimes; instead, it is aimed at all those armchair crime buffs who, like me, occasionally scratch their heads and try to recall the basic facts of some notorious or curious case of murder from the past. It is also based on the many questions and enquiries I have received after lectures and in letters I have received from the readers of my books over my twenty years as a crime historian and includes many of the cases that have intrigued me over those years, particularly those that contain some curious twist, a significant point of law or milestone of detection or forensics within it, or remain an unsolved mystery.

In this volume you will discover such gobbets of murderous information as: there was a murder between rival elephant keepers at London Zoo in 1928; not just one but two murders have been committed on Potters Bar Golf Course in Hertfordshire; what was The Otterburn Mystery and how many Brides did George Joseph Smith drown in the bath? Learn what was found down the drains of a house in the leafy suburb of Cranley Gardens in Muswell Hill in 1983, discover who was the first internet serial killer, find out where there is a book charting an account of an infamous murder bound in the murderers own skin, and learn of some of the strangest weapons that have been used by murderers, items as diverse as a tubular chair, a gas ring dismantled from a cooker and even a 10lb jar of pickles.

You can use this book to create a crime quiz, you can read it from cover to cover or dip into it as you please, there are no rules and you will soon see the ease with which one can enliven conversation, intrigue friends and even impress a few ardent crime fans with the knowledge you have obtained from this book.

Neil R. Storey, 2013

NORTH & MIDLANDS

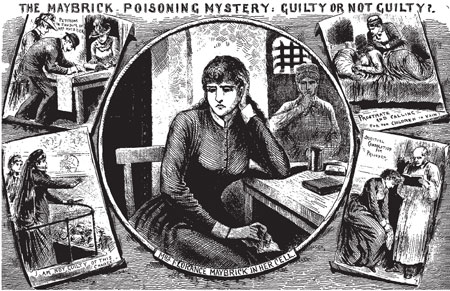

Mrs Maybrick

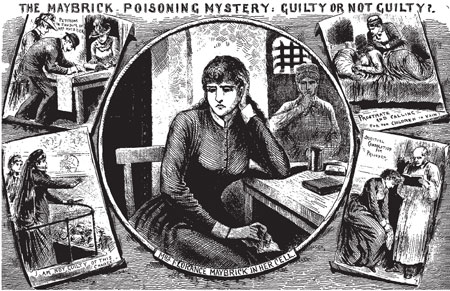

One of the most sensational trials of a woman in the late nineteenth century was that of Florence Florie Maybrick, a pretty American girl from a good family. She married James Maybrick, an English cotton broker, some twenty-three years her senior, in 1881. They made their home at Battlecrease House in the Liverpool suburb of Aigburth. Maybrick was not easy to live with; he was known to take concoctions of drugs and maintained a number of mistresses, one of whom bore him five children. The disenchanted Florie had a few clandestine liaisons of her own, including a dalliance with her husbands brother, Edwin. James heard of her affair with local businessman Alfred Brierley and after a violent row, during which he assaulted Florie, Maybrick demanded a divorce.

In April 1889, Florie bought flypapers that she knew contained arsenic and soaked them in a bowl of water to extract the poison for cosmetic use. On 27 April 1889 James was taken ill, the doctor was called for and he was treated for acute dyspepsia, but his condition declined and he died on 11 May 1889. Suspicious of the cause of death, Maybricks brothers requested that James body be examined. Traces of arsenic were detected, not enough to prove fatal, but they were present and Florie was arrested and tried for murder at the Liverpool Assizes in July 1889. The evidence against her was flimsy there was no way of proving Florie had administered the arsenic to James but it seems her private affairs drew enough condemnation and she was found guilty, more for lack of morals than for direct evidence of murder. Florie was sentenced to death, which was eventually respited in favour of penal servitude. Her case became a cause clbre , but she was only released after serving fourteen years in January 1904. Florie returned to the United States and died in poverty in 1941. Among her few remaining possessions was discovered a tatty family bible, and pressed between its yellowed pages was a scrap of paper which had written upon it, in faded ink, the directions for soaking flypapers for use as a beauty treatment.

The Strange Death of Sidney Marston

Marjorie Yellow and Emily Thay were sisters, one in her late teens the other in her early twenties. Both had already been married and, scandalously for the time, both had separated from their husbands. Emily was spending the weekend with her sister, who was now living with another man named Herbert Gwinnell at Willow Crescent on Cannon Hill in Birmingham. Shortly after 7.30 p.m. on 24 October 1932, Emily rushed out onto the street screaming Murder! Marjorie followed, asking for help to put a man out of their house. As a passer-by ran up, a man stumbled out of the house; he had been stabbed in the chest and with his dying breath gasped, I have done nothing, before he collapsed onto the porch and died.

The sisters were charged with murder but the evidence produced against them was both confusing and conflicting. The dead man was identified as Sidney Marston, who was described as a thickset young man who could look after himself. There was not a trace of a defensive wound on his person or sign of a struggle and in his pocket was the blade of a knife; the handle lay nearby. Yellow said Marston had stabbed himself; there was talk of a missing 10 s note, which was found in Marstons pocket. Yellow denied knowing Marston, but later said she had met him at a dance; other casual remarks she was recorded as making were, Hes only shamming. Hes done that before, and, most curiously, They dont hang women do they? Even the great Sir Bernard Spilsbury, Home Office pathologist, could not attribute an opinion of blame or guilt to any of the parties, and a verdict of not guilty was passed on the sisters.

Nurse Waddingham

Known in the annals of crime as Nurse Waddingham, Dorothea Waddingham had no formal training as a nurse, and what medical knowledge she did have was probably obtained when she worked as a ward maid at an infirmary in Burton-on-Trent. Waddingham had a murky past and had served prison terms for fraud and theft. She gained her appointment as matron only because she and her husband turned their home on Devon Drive, Nottingham, into a private nursing home for elderly and infirm patients. Two patients, a Mrs Baguley and her daughter, both of who had named Waddingham as a beneficiary in their wills, died a short time apart. Suspicions arose and a post-mortem examination was ordered on the body of the daughter over three grains of morphine were found in her internal organs. Mrs Baguleys body was then exhumed and it was found that she too had died from morphine poisoning. Tried and found guilty, Waddingham was executed on 16 April 1936 by Thomas Pierrepoint at Winson Green Prison, Birmingham.

Next page