CHAPTER 1

He Could Not Tell What Possessed Him

1817

her skull had been smashed by

repeated and violent blows.

O n 7 July 1817, Elizabeth Sheppard left her mothers house in the Nottinghamshire village of Papplewick, and began the long walk to Mansfield. Seventeen-year-old Elizabeth, whose fully developed figure proclaimed her as no longer a mere girl but a finely-formed young woman, was seeking work. She hoped to find a post as a domestic servant, and Mansfield, a large and prosperous market town some five miles away, offered better prospects for employment than her native village. It was early afternoon when she set off, some time between 12 and 1 pm, and her mother remembered afterwards that Elizabeth was wearing a pair of shoes newly bought the previous Sunday, and that she carried a light-coloured cotton umbrella. No doubt she smiled as she left the family home that bright summer day, on a journey that promised better times for them both.

She was not to return alive.

Papplewick village, home of Elizabeth Sheppard, from which she made her last journey to Mansfield in July 1817. Dennis Middleton

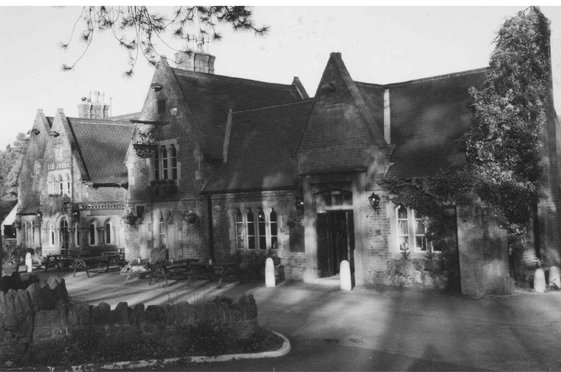

Griffins Head Inn , Papplewick. Dennis Middleton

It seems Elizabeth made the journey to Mansfield without incident, for she was seen leaving the town around 6 pm. Evidently she intended to return home to Papplewick, but this time her journey was never completed. Early on the morning of 8 July her body was found in a roadside ditch, a short distance from the third milestone out of Mansfield. Those who stumbled upon her were shocked to discover that her skull had been smashed by repeated and violent blows. Nor was there any need to search for the murder weapon. A five-foot hedge stake lay close beside the horribly battered corpse, its end thickly stained with clotted blood.

At first the murder seemed not only brutal but motiveless, as Elizabeth had carried no money with her, and there was no indication that any sexual assault had been attempted, but once it was confirmed that the girls shoes and umbrella were missing, the investigators had a lead to follow. Further enquiries revealed that a former serving soldier, Charles Rotherham, had been seen drinking in the Hut, a roadside inn not far from the scene of the murder, soon after Elizabeth had been killed. Later that night, he had turned up at the Three Crowns Inn at Redhill, where he had offered both the shoes and umbrella for sale. No-one took up the offer, and Rotherham retired to bed for the night. When he left the inn, the shoes stayed behind in his bedroom, but he still had the umbrella with him, and eventually found a buyer for it in the village of Bunny.

Market Place, Mansfield, where Elizabeth went to find employment. Bentinck monument in centre of picture, former Town Hall on left. Dennis Middleton

By this time his luck was running out. An officer of the law, Mr B Barnes of Nottingham, set off in pursuit of the suspect, following Rotherhams trail beyond the county boundary and into Leicestershire. Barnes finally tracked his quarry down at Loughborough, where the much-travelled Rotherham was arrested, making no resistance.

Charles Rotherham was thirty-three, a citizen of Sheffield, and had only recently been discharged from army service. Originally apprenticed to a scissor-grinder, he had subsequently enlisted as a driver in the Artillery, serving for twelve years. During this time he had seen action in Egypt, and as a member of Wellingtons Peninsular army in the ferocious battles of Ciudad Rodrigo, Badajoz, Salamanca and Toulouse.

No stranger to military violence, Rotherham appears to have suffered the fate common to many ex-soldiers of this and later periods. Cast off without money or employment when the Napoleonic Wars came to an end, he seems to have drifted aimlessly from one village to another, looking for easy money to fund his drinking habit and keep him from starvation. In the end, his wandering, purposeless existence had led to the fatal encounter with Elizabeth Sheppard on the evening of 7 July.

The Wednesday after his arrest, Charles Rotherham was taken to the coroners inquest at Sutton-in-Ashfield, where the cause of Elizabeths death was confirmed as being due to skull fractures from several blows with the hedge stake. Journeying back to Nottingham with his captor, Rotherham finally confessed to the murder. As they reached the place where Elizabeth had died, he pointed out the spot to Barnes, and showed him the hedge on the far side of the road, from which he had pulled the stake that ended his victims life.

Questioned as to why he had done such a terrible thing, Rotherham offered neither reason nor excuse, claiming that he could not tell what possessed him at that moment. Coming up behind Elizabeth without a word, he had wielded the stake like a massive spear, using the pointed end to batter the head of his victim with a succession of frenzied blows until he was sure of her death. Perhaps it was true, as he claimed, that this was an unmotivated impulse killing, but judging from his subsequent actions the thought of robbery must have crossed his mind soon afterwards. Rotherham had turned out the dead womans pocket and, finding it empty, cut open her stays (corsets) in the hope of finding money concealed inside. Once again he was out of luck, and had to settle for the shoes and umbrella of his victim. These items in turn had brought him nothing but trouble, providing his pursuers with clues to his whereabouts, and eventually leading them to him.

Hutt Hotel , Ravenshead, at which Rotherham drank after murdering his young victim. Dennis Middleton

His confession made, there could now be no hope for Charles Rotherham. Brought before the Honourable Sir John Bayley at Nottingham County Hall on 25 July, he pleaded guilty to the charge of murder, but was apparently prevailed upon by his judge to go through with the trial procedure. Presumably Sir John was anxious that justice was seen to be done; either that, or, having come prepared for the full-length legal process, he felt cheated by Rotherhams immediate confession of guilt. In the end it made no difference, for there could only be one outcome. Rotherham was found guilty of wilfully murdering Elizabeth Sheppard on 7 July, and sentenced to death.

Three days after the court appearance, on 28 July 1817, he was hanged at Nottinghams Gallows Hill before a large, and no doubt appreciative, crowd, for whom public executions were one of the main entertainments of the early nineteenth century. How attentive they were to the speech-cum-sermon of the Reverend J Bryan, who addressed the assembled multitude at great length, is not recorded, but one suspects that they took a keener interest in the hanging itself. The clergyman prayed with the condemned man, who was then immediately launched into eternity. Following the execution, Rotherhams body was cut down and borne back to the County Hall where, after being worked on by the surgeons, it was left exposed to public view in the Nisi Prius Court as a grim deterrent to other would-be criminals. Mercifully, once a suitable interval had passed, the corpse was taken away and buried at the back of St Marys Church. It was a sad and ignominious end to the life of a man who had served his country for so long under one of its greatest generals.