Lockdown

Originally published in Brazil in 1999 as Estao Carandiru by Companhia das Letras

First published in Great Britain in 2012 by Simon & Schuster UK Ltd

A CBS COMPANY

Copyright 1999 by Drauzio Varella

English language translation Alison Entrekin, 2012

This book is copyright under the Berne Convention.

No reproduction without permission.

All rights reserved.

The right of Drauzio Varella to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988.

Picture permissions: Drauzio Varella (Luiz Carlos Murauskas)

Simon & Schuster UK Ltd

1st Floor

222 Grays Inn Road

London

WC1X 8HB

www.simonandschuster.co.uk

Simon & Schuster Australia

Sydney

Simon & Schuster India

New Delhi

A CIP catalogue copy for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN: 978-1-84983-865-8 (B format paperback)

ISBN: 978-1-47110-106-9 (Export trade paperback)

eBook ISBN: 978-1-84983-866-5

Typeset by Hewer Text UK Ltd, Edinburgh

Printed and bound in Great Britain by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon, CR0 4YY

Introduction

W hen I was young, I would watch black-and-white prison films in which the inmates wore uniforms and planned breathtaking escapes while riveted to my chair.

In 1989, when I had already graduated and had been working as an oncologist for twenty years, I filmed a video about AIDS in the infirmary of the So Paulo State Penitentiary, a building designed by Brazilian architect Ramos de Azevedo in the 1920s, in the Carandiru prison complex in the city of So Paulo. When I walked in and the heavy door slammed behind me, I felt the same tightening in my throat that I had as a boy at matines in Cine Rialto, in the So Paulo neighbourhood of Brs.

In the following weeks, I couldnt get the images of the prison out of my mind. The prisoners at the doors of their cells, the unshaven warder, a distracted military police officer on the rampart, holding a machine gun, echoes in the gloomy corridor, the smell, the swagger of hardened criminals, tuberculosis, cachexia, loneliness and the silent figure of Dr Getlio, my former student, who cared for the prisoners with AIDS.

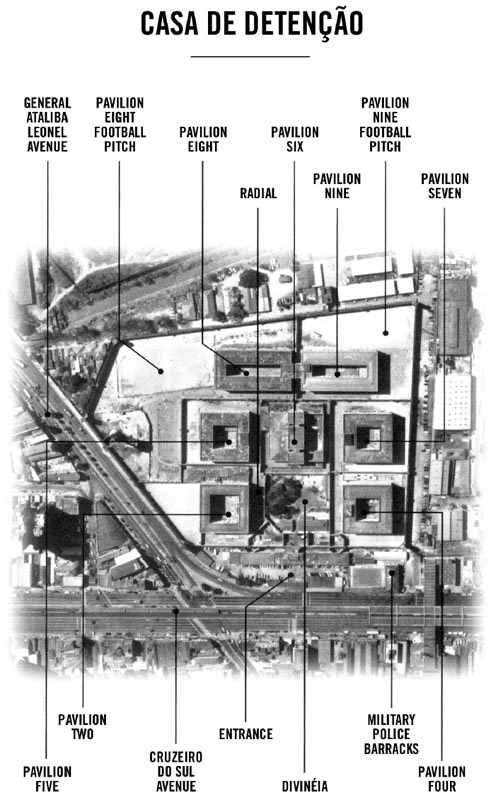

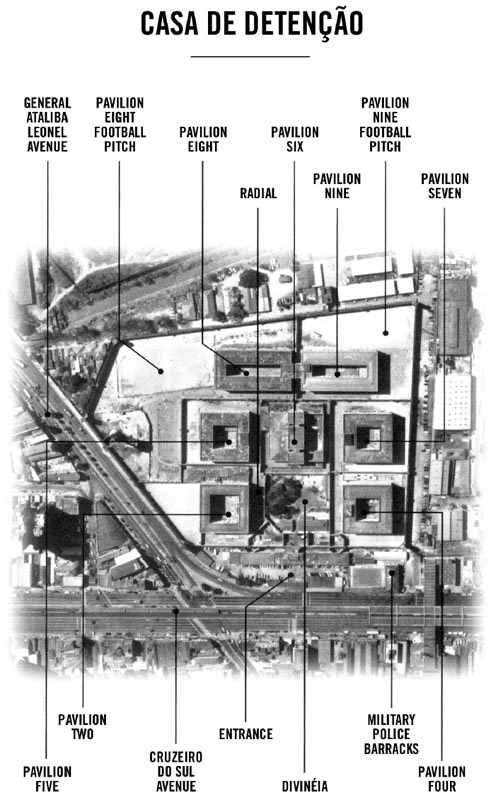

Two weeks later, I went to see Dr Manoel Schechtman, in charge of the prison systems medical department, and offered to implant a voluntary AIDS-prevention programme at the prison. Dr Schechtman told me that the epidemic wasnt as bad at that penitentiary as at the Casa de Deteno, Brazils largest prison, with 7200 inmates, located in the same complex, just ten minutes from the bustling heart of downtown So Paulo.

The programme was implemented in 1989. With the support of the private Paulista University, we conducted epidemiological research into the prevalence of HIV, organised talks, recorded videos, published the comic book O Vira Lata [The Stray], written by Paulo Garfunkel and illustrated by Lbero Malavoglia, and I treated the sick. As the years went past, I gained confidence and was able to pass freely through the prison. I heard stories, struck up true friendships, and furthered my knowledge of medicine and many other things. The experience gave me an insiders understanding of certain mysteries of prison life to which I wouldnt have had access if I hadnt been a doctor.

In this book, I try to show that the loss of freedom and restriction of ones physical space do not lead to barbaric behaviour, contrary to what many people think. In captivity, men, like all other large primates (orang-utans, gorillas, chimpanzees and bonobos), create new rules of conduct in order to preserve the integrity of the group. In the case of the Casa de Deteno, this adaptive process was governed by an unwritten penal code, as in Anglo-Saxon law, which was applied with extreme rigour: Among us, theres no statute of limitations, Doctor.

Paying ones debts, not informing on fellow inmates, respecting other peoples visitors, not coveting the neighbours wife, and exercising solidarity and altruism gave prisoners dignity. Failure to observe the above was punished with social ostracism, physical punishment and even the death penalty. In the world of crime, a mans word is stronger than an army.

The objective of this book is not to speak out against an antiquated penal system, to offer solutions for crime in Brazil or to defend human rights. As in the films of old, I seek to walk among the characters who inhabited the prison: thieves, swindlers, smugglers, rapists, murderers and the handful of unarmed warders who watched over them.

The narrative is interrupted by the characters themselves so that readers may appreciate their stories first-hand. For ethical reasons, the incidents described didnt always happen to the characters to whom they have been attributed. As the criminals themselves used to say: In a prison, no one knows where the truth resides.

Carandiru Station

Prison is a place inhabited by evil.

I took the metro to Carandiru Station, where I got off and turned right, in front of the military police barracks. In the background, as far as the eye could see, stretched a grey wall with guard towers. Next door to the barracks was a majestic entrance with CASA DE DETENO written above it in black letters.

The gate from the street led into a full parking lot. Through it circulated lawyers, women carrying plastic bags and corpulent warders in jeans who talked about work, laughed at one another and changed the subject whenever someone they didnt know approached. They had to be greeted decisively; otherwise, your hand would be crushed by their handshake.

Thirty paces into the complex was a small administration building, behind a green gate in which a smaller gate for pedestrians was set. You didnt need to knock to enter; all you had to do was put your head near the window in the gate and the guards poorly lit face would appear, telepathically, on the other side.

The opening of the gate obeyed the old prison routine, according to which a door could only be opened when the ones before and after it had been closed. It was good manners to wait without useless demonstrations of impatience.

I heard the clink of the gate unlocking and found myself in the Rat-trap, a barred atrium with two booths on the left, where visitors had to identify themselves. Behind the booths was a corridor leading to the director generals office, which was large and full of light. The table was old. On the wall behind it was a photograph of the governor and a copper plate, hung there by one of the directors, an experienced jailer, that said: It is easier for a camel to pass through the eye of a needle than for a rich man to enter the Casa de Deteno.

I returned to the Rat-trap, waited for the inner gate to open and found myself facing the wall that surrounded the prison, guarded by military police officers armed with submachine guns.

I stepped into Divinia, a large funnel-shaped courtyard. At the narrow end was the body search room, a compulsory stopover for those entering the prison, except for doctors, directors and lawyers. Before gaining access to the pavilions, it was necessary to enter this room and lift your arms up in front of the friskers, who would merely pat your waist and the sides of your thighs.

Frisking was another prison ritual.

Those who thought such a mechanical search was just for show, however, were mistaken: people were frequently caught with drugs, arrested and ended up doing time in the Criminal Observation Centre.

Once, five inmates from Pavilion Five armed with knives took some warders hostage in the laundry and demanded to be transferred to another prison. Police officers and reporters with cameras swarmed to the prison door. A warder took advantage of the confusion to enter carrying 1.5 kilos of cocaine. He was caught in the body search room. Jesus, director of security, a former professional wrestler turned Protestant pastor, did everything in his power to identify who the cocaine was for.

Next page