Table of Contents

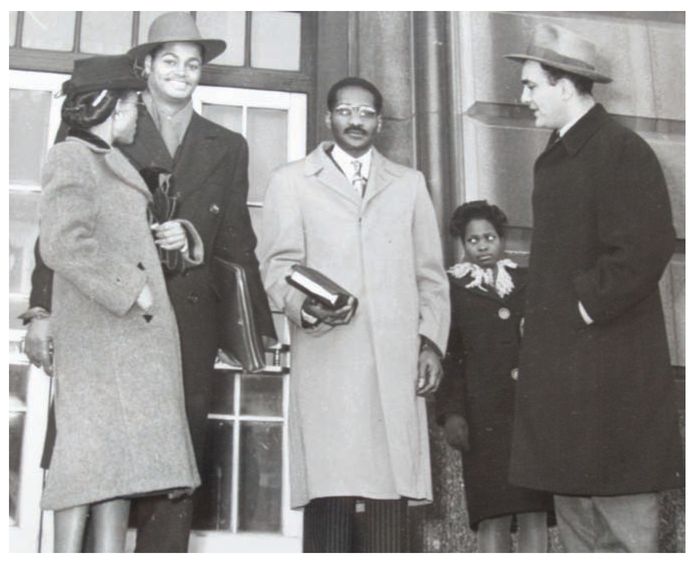

(left to right): Mrs. Annie Hickman, UAW leader Willoughby Abner, James Hickman, and SWP Chicago organizer Mike Bartell.

(left to right): Mike Myer, William Temple, Sidney Lens, Leon Despres, Willoughby Abner, UAW leader Charles Chiakulas, and Mike Bartell. Annie Hickman is standing in front.

For my mom, dad, and uncle Leo,

and grandpa Joe,

a Boston firefighter

The landlord furnished everything. But you pays for it. And he dont work.

Introduction

Nobody knows about it

I want you to write about the Hickman case, Frank Fried told me, gripping his cane with one hand and gesturing with the other. It was the best thing we ever did, and nobody knows about it.

Frank is a retired music impresario. The biggest music event he ever organized was bringing the Beatles to Chicago. Frank has lived in California for many years, and he was in Chicago in spring 2008 to celebrate the birthday of a mutual friend. We were sitting on the porch and talking about his life. He was eighty-one at the time and was facing the possibility of open-heart surgery. I think he was afraid that the Hickman story might completely disappear if the surgery wasnt successful.

What was the Hickman case? I asked.

He paused for a moment and said, Go read the Bartlow Martin article in Harpers in 1948, then go from there. I followed his instructions, and this book is the product of two and a half years of research and writing.

The Hickman case is the story of an excruciating family tragedy and a triumph of justice against long odds. The needless deaths of four of the youngest children of James and Annie Hickman in a tenement fire in January 1947, Jamess shooting and killing of the buildings landlord (whom he blamed for the fire), his trial, and the campaign to win his freedomrecords of these events have endured mostly as fleeting references or footnotes in books on housing in postwar Chicago. Living memories of them are held almost entirely by a tiny number of the fires survivors and those who fought for Jamess freedom. There were only two living as of fall 2010.

Early on I was warned that it might be impossible to write a book about the Hickman case. Writing a book from scratch can be challenging even in the best of circumstances. The Hickman case presented many hurdles: most of the witnesses have passed away, and the Hickman murder trial transcript disappeared long ago. But I settled on an approach that I believe will allow the Hickman story to be told in full for the first time.

I have tried to tell the story first and foremost from the viewpoint of James and Annie Hickman, relying heavily on their testimony at the Cook County coroners inquest and interviews with the journalist John Bartlow Martin. Their story, of course, was part of a much larger historical dramathe Great Migration, when millions of African Americans traveled north to find a measure of the dignity and freedom that were absent from the Jim Crow South. When they got to Chicago, the Hickmans and others encountered differences in culture and climatebut unfortunately racism still presented obstacles, particularly in access to decent housing.

I have tried to weave the lives of the many people who played a part in the Hickman case into the story, from Mike Bartell of the Socialist Workers Party to UAW leader Willoughby Abner to the movie and stage star Tallulah Bankhead, along with many others. At some points I pause to explain the historical background of the individuals and institutions in the Hickman drama. In an era when newspapers, particularly Black community newspapers, play a diminished role in our lives, the Chicago Defenders work to expose the exploitation and racial oppression of Chicagos Black ghetto and advocate for social change must be explained in depth. The same goes for the radical activists of the Socialist Workers Party who came to Hickmans aid. These are not detours from the main story but integral parts of it.

Much of the history in this book is not easily accessible, and it is certainly given no prominence by those who run the city of Chicago. This year, as every year, millions of tourists will come to Chicago to experience a city that is promoted as both quintessentially American and world class. With their water bottles and digital cameras they will descend on Michigan Avenue and the nearby Millennium Park. They will be shuttled around the city in free buses (for tourists only) between the expensive shopping districts, such as the Magnificent Mile, and the safe confines of the Field Museum, the Shedd Aquarium, the Adler Planetarium, and the Museum of Science and Industry. Few, if any, will venture into the real city. Those who come in search of history will have a hard time finding it. They may unknowingly brush up against it or walk over it, but like everything else in the City That Works, it will be sanitized and packaged for tourism. The city even frowns on the gangster tour, even though one of the reasons that tourists visit Chicago is the lure of its Prohibition-era gangster past. Al Capone is still the worlds best-known Chicago resident.

The best example of this historical packaging is the famed architecture tour. It is a pleasurable trip along the Chicago River during which enthusiastic volunteers tell an uplifting story of a city that rose from the flames of the Great Chicago Fire of 1871, as the great architects of the world helped rebuild it. There is no discussion of such messy issues as the lack of safe, decent housing that led to the fire that destroyed most of the city, or the many fires since then, or, most important, the victims of these fires.

This book is the story of one such fire. Like much of Chicagos real and unsanitized history, the site of the Hickman tragedy is not on the tourist maps and has been literally buried. The building at 1733 West Washburne Avenue no longer exists; it has been buried beneath a nondescript residence for seniors. One warm, lazy summer afternoon I walked to the Near West Side to see the site. Standing there in the bright sunlight, I tried to imagine what the neighborhood must have been like when the Hickmans lived there, but it was almost impossible.

The area has been mauled by institutional expansion for decades. The land just east of what was 1733 West Washburne has become Parking Lot M of the University of Illinois at Chicago (UIC). Across the street is the rear entrance to a UIC research facility, a beige building with blue-tinted windows, typical of ugly corporate and public office buildings built in the 1970s and 80s. To the west and south are several blocks of vacant land peppered along the edges with parking meters. Its a strange sight to behold: it looks as though some powerful weapon that destroys buildings while avoiding any damage to parking meters had been detonated. There is nothing left of the old neighborhood except the elevated train that roars by two stories above the ground. I tried to imagine riding the L that cold January night between 11:30 p.m. and midnight. What would I have encountered? An inferno lighting up the night sky? A blare of sirens and glare of lights from fire engines? Neighbors rushing to the building to help? Two figures falling from the top floor? Would I have had a frontrow view of a catastrophe or just a hint that something was wrong?