THE GREAT DIVORCE

THE GREAT DIVORCE

Ilyon Woo

A Nineteenth-Century

Mothers Extraordinary

Fight against Her Husband,

the Shakers, and Her Times

Copyright 2010 by Ilyon Woo

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review. Scanning, uploading, and electronic distribution of this book or the facilitation of such without the permission of the publisher is prohibited. Please purchase only authorized electronic editions, and do not participate in or encourage electronic piracy of copyrighted materials. Your support of the authors rights is appreciated. Any member of educational institutions wishing to photocopy part or all of the work for classroom use, or anthology, should send inquiries to Grove/Atlantic, Inc., 841 Broadway, New York, NY 10003 or permissions@groveatlantic.com.

Published simultaneously in Canada

ISBN-13: 978-0-8021-9705-4 (e-book)

Atlantic Monthly Press

an imprint of Grove/Atlantic, Inc.

841 Broadway

New York, NY 10003

Distributed by Publishers Group West

www.groveatlantic.com

To my parents

Live with me, my child! The foxes have holes and the birds of

the air have nests, but I have not where to lay my head.

Go child, and I will go with you; if you go through the waters,

the floods shall not overflow you; and if you go through the fire,

it shall not kindle upon you; and if you go to the ends of the earth,

I will never leave you nor forsake you.

Mother Ann Lee

CONTENTS

THE GREAT DIVORCE

Enfield, New Hampshire

May 1818

Five years after the children first disappeared, it had come to this: a hundred strangers circling the Shaker village, torches lit. It was an unseasonably cold night for May, with snow on the ground for reasons no one could explain. The intruders crouched along the trim white fences, hovered by the low stone walls, and rode their horses around the villages periphery, marring the strange spring snow. It was said that five hundred more might come by morning.

Leading the mob was the mother of the missing children, Eunice Chapman, a woman so small that she might have been mistaken for a child herself, her eyes scanning the darkened village. Somewhere herein one of the closed workshops or barns, or perhaps in the looming, four-story dwelling where the Shakers spent their nightswas her former husband, James, and with him, the children he had stolen from her: Julia, Susan, and George.

The Shakers were saints, James had declared, but to her, these so-called Believers were as far from holy as they could be: They were responsible for separating her from her family, and for hiding her children. Now, after a long search and years of legal warfare, she was closer than she had ever been to bringing her children home. She would do whatever was required. As she had warned the Shakers two days before, I will scare you yet and make you tremble.

But James was equally resolute. He had once declared that he would sooner kill himself than give up his children, and days earlier had announced that he would rather send his children floating down the river than see them reunited with their mother. By law, children rightfully belonged to their father, and James Chapman had no intention of surrendering his kin.

There had never been much love between the Chapmans, not even when they were courting more than fifteen years earlier. Yet even when the gulf between them had been widestwhen the two would sleep on separate floors of their home or James would sleep with other women, when Eunice would threaten James and he would spit into her facethey had never imagined that they would come to blows like this, with hundreds gathered on either side of them, and with everything between them distorted by the glare of torchlight.

The story leading to this standoff begins with America in a time of revolution. The United States was at war with the British during the so-called Second American Revolution, or the War of 1812. The government was nearly bankrupt and a spirit of speculation was running high, propelling the country toward its first financial crash, the Panic of 1819. Gleaming new steamboats dotted the nations harbors, and freshly paved roads led the way out West, testament to the transportation revolution then under way. Even legal tradition was coming unmoored as Americans, newly released from the constraints of British rule, sought to define justice in their own terms. And all across the country, religious revivalism raged, stoked by the hopes and anxieties of a people who yearned for something definitive, if not in this life, then in the hereafter.

It was during this period of unrest and discovery that Eunice Hawley Chapmana woman born two years into the War for Independence, on November 22, 1778began a revolution of her own, one that eventually made her known across the country. It started when her husband, a troubled merchant named James Chapman, sought to join the Shakers near Albany, New York, and resolved to take his children with him.

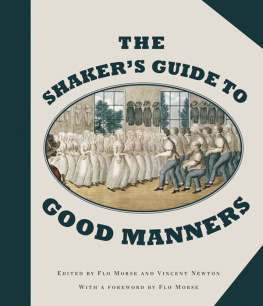

Today, the Shakers are remembered mainly for their handiworkoval boxes, straight-back chairs, and spare, modern-looking furniture that has sold for hundreds of thousands of dollars apiece. Other products of Shaker culture are also familiar, if not always recognized as Shaker, such as the song Simple Gift, popularized in Aaron Coplands Appalachian Spring. In contrast, the people behind these objects have largely been forgotten. As Shaker Sister Mildred Barker once remarked, she almost expect[ed] to be remembered as a chair or a table. In the second decade of the nineteenth century, however, the Shakers were a vibrant order, several thousand strong and growing, with sixteen communities stretching across eight statesfrom Maine to Indiana and down to Kentucky. And they were hardly the exemplars of American culture they are now. Even then, the Shakers were known for their excellent wares, but they also aroused deep controversy on account of their radical religious beliefs.

Brought to America by the charismatic English visionary Ann Lee, the Shakers believed in the continuing revelation of Christthat ones relationship with God was determined not by books or creeds but by the present experience of the divine. They believed in perfectibility, that as Believers they could overcome sin, and that together they could create a heaven on earth. What made the Shakers radicals, however, was not merely their religious enthusiasm, or their belief that salvation could be guaranteed, but the extreme mandates of their faith. All Shakers were required to renounce their sexuality, property, and family as the first step toward being liberated from earthly sin.

When James Chapman decided to bring his children into this unorthodox society, there was little that his wife could do to oppose him. In the 1810s, children were the exclusive property of their fatherheirs, as well as sources of social security. Decades would pass before mothers had any rights to their children, let alone custodial preference in the eyes of the law. Wives, too, belonged to the husband and had few legal rights. Given Jamess decision, Eunice only real options were to join the Shakers to be with her children or to give up her family and prepare to live alone.

But Eunice Chapman was an uncommon woman. Famously seductive, willful, and canny, she learned through difficult experience what was expected of her as a woman and how to exploit those expectations. She turned feminine weakness into a source of political strength, using every strategy available to herincluding some forbidden onesin her quest for her children.

Next page