Table of Contents

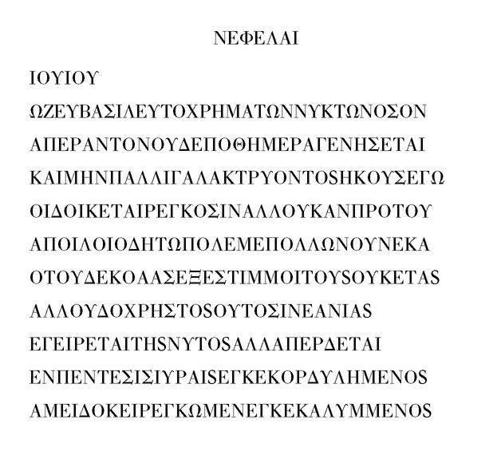

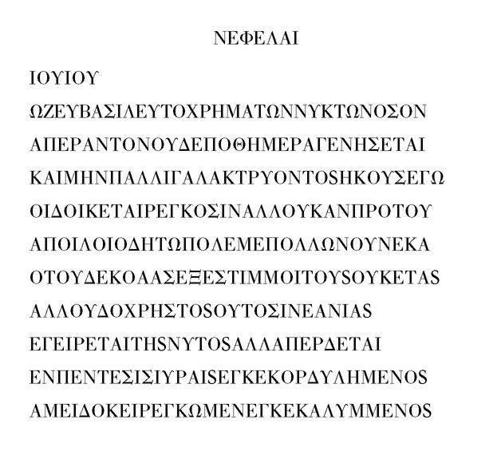

The first ten lines of Clouds as they would have appeared on a fourth century B.C. ms.

New American Library

Published by New American Library, a division of

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street,

New York, New York 10014, USA

Penguin Group (Canada), 10 Alcorn Avenue, Toronto,

Ontario M4V 3B2, Canada (a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.)

Penguin Books Ltd., 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

Penguin Ireland, 25 St. Stephens Green, Dublin 2,

Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd.)

Penguin Group (Australia), 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124,

Australia (a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty. Ltd.)

Penguin Books India Pvt. Ltd., 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park,

New Delhi - 110 017, India

Penguin Group (NZ), cnr Airborne and Rosedale Roads, Albany,

Auckland 1310, New Zealand (a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd.)

Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty.) Ltd., 24 Sturdee Avenue,

Rosebank, Johannesburg 2196, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd., Registered Offices:

80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

First published by New American Library,

a division of Penguin Group (USA) Inc.

First New American Library Printing, February 2005

Copyright Paul Roche, 2005

All rights reserved

( See page 716 for permissions information. )

NEW AMERICAN LIBRARY and logo are trademarks of Penguin Group (USA) Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data:

Aristophanes.

[Works. English. 2005]

The complete plays / Aristophanes ; translated by Paul Roche.

p. cm.

eISBN: 9781101378717

1. AristophanesTranslations into English. 2. Athens (Greece)Drama. I.

Roche, Paul, 1927- II. Title.

PA3877.A1R57 2005

882.01dc22 2004056681

Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book via the Internet or via any other means without the permission of the publisher is illegal and punishable by law. Please purchase only authorized electronic editions, and do not participate in or encourage electronic piracy of copyrighted materials. Your support of the authors rights is appreciated.

http://us.penguingroup.com

TO PATRICK HORSBRUGH

o oo

Acknowledgments

My debt to Jeffrey Henderson, editor of the Loeb Classical Library and Professor of Classical Studies at Boston University, knows no bounds. His translations of Aristophanes in the Loeb series with accompanying Greek text is scrupulously faithful and expressed in language that is wholly contemporary. I was guided and steadied by him throughout and I found his footnotes invaluable.

I should also like to express my gratitude to Mrs. Pat Gilbert-Read, who trawled through all eleven of these plays and rescued me from many an infelicity.

Introduction

ARISTOPHANES

The dates of Aristophanes birth and death are variously given, but 445-375 B.C. is a possibility. We know that he was considered too young to present his first three plays in his own name: the lost Daiteleis ( Banqueters ), which won second prize at the Lenaea in 427 B.C., when he would have been only about eighteen; the lost Babylonians , which won second prize in 426 B.C.; and Acharnians , which brought him first prize in 425 B.C. when he was barely twenty. These plays and the four that followed over the next four years are the work of a very young man endowed with the courage to level unrelenting attacks on no less than the head of statethe demagogic Cleon.

Like the great tragedians Aeschylus, Sophocles and Euripides (and, I expect, the poets of all ages), he decried the destructiveness and sheer stupidity of war, and in his most celebrated plays he warned and pleaded against it. Yet for twenty-seven years of his writing life, with one brief interval, Athens was at war with Sparta in an internecine struggle that finally left her exhausted and shorn of her glory, never fully to recover.

Aristophanes had no respect for shoddy politicians like Cleon, who plunged Athens into campaigns that led to defeat and decline, and he lampooned them without mercy. He himself came from a landowning family and his political outlook was conservative. Not necessarily in favor of oligarachy, he believed that democracy was best served by the brightest minds and not by selfish, clamorous demagogues. He was conservative too in his general thought, defending religion though he laughed at the gods, and he was suspicious of contemporary philosophy. He mocked Socrates as a Sophist, knowing full well he was as anti-Sophist as Aristophanes himself; it was just too easy to use him as a scapegoat because he was well known and easy to parody. Aristophanes conservatism did not extend to his language, which is almost unimaginably rich and varied. The obscenity that crops up here and there is funny because it is unexpected. When one considers the milieu in which the plays were presentedunder the auspices of the State, to the entire population, at a religious festival under the presidency of a priest and on consecrated groundhow could it not be hilariously incongruous? It was as if somebody (preferably the grandest dignitary present) trumpeted a fart in a solemn moment at high mass.

But it is incongruous too because the rest of Greek literature from Homer to Thucydides (if we except Sappho) is so well behaved. Yet we ought not to be surprised by the phallic thrust of Aristophanes jokes, because the origins of comedy are undoubtedly found in fertility rites at the dawn of drama. Sex, after all, is the oldest human hobby.

Having said all this, I feel it is important to add that the plays of Aristophanes are serious. In them he confronts and dares to laugh out of court some current trend or action or human aberration. He recognized that the prime function of the poet is to reduce to orderShelleys unacknowledged legislator of this worldin other words, to preserve a world worth living in, with the greatest political and personal freedom consonant with order, and the leisure to enjoy it all.

This is essential teaching at an organic level, and it is done not by giving informationthe way of prosebut by lifting the spirit to a new plane of truth and beauty. Ut doceat, ut demonstrat, ut delectat. Such is the brief of the poet, and it is this last, to please, which is the touchstone of lasting poetry. This does not mean that poetry deals only with the beautiful but that when it deals with ugliness it remains in itself beautiful.

Not only was Aristophanes one of the greatest poets of antiquity but, in the words of Lemprieres Classical Dictionary , the greatest comic dramatist in world literature: by his side Molire seems dull and Shakespeare clownish.

Be that as it may, the lyrics of Aristophanes present the translator with an irresistible but crippling challenge, and the best he can do to meet itif he is really trying to translate and not just to paraphrase or adaptis ineluctably doomed to be a poor reflection of the original. Nevertheless, even this pittance is well worth trawling for.

Next page