The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

Contents

For Elaine and Matt

List of Illustrations

Acknowledgements

Many of the individuals who helped in the preparation of this book deserve special mention. They are: Paul Alpers, Emily Bartels, Austin Burke, Patrick Cheney, Jay Fliegelman, Jonathan Goldberg, Lisa Hopkins, Roy Kendall, Elizabeth Leedham-Green, Leah Marcus, Jack Macrae, Charles Nicholl, Stephen Orgel, Richard Priess, Sue Riggs, Rob Watson and Alex Woloch. I thank Don Lamm for his expert and unstinting guidance at every stage.

This is also the place to remember the teachers who introduced me to Christopher Marlowe Dan Seltzer and Harry Levin.

D.R.

Prologue: Reinventing Marlowe

Christopher Marlowe was born on the threshold of modern theatre, before the words playwright and dramatist had entered the English language. The earliest playhouses appeared during his boyhood, when custom-built theatres sprouted on the outskirts of London. These new establishments had a limited purpose: skilled actors performed makeshift dramatic entertainments for an audience of unpracticed theatregoers. Marlowe endowed this rickety start-up venture with a precious legacy of intellectual property. He offered spectators a thrilling repertory of poetic tragedies that spoke to their most urgent concerns grinding poverty, class conflict, erotic desire, religious dissent, and the fear of hell. Marlowes eight-year career exploded with masterpieces. Tamburlaine the Great, Dr Faustus, The Jew of Malta, and Edward II transformed the Elizabethan stage into a place of astonishing creativity.

He was the greatest playwright that England had ever seen. William Shakespeare, who gained prominence just a few years later, mourned Marlowes passing in As You Like It: Dead shepherd, now I find thy saw of might / Who ever loved, that loved not at first sight? Ben Jonson hailed the inventor of Marlowes mighty line. The dramatists enemies were just as adamant about his vices. During the months leading up to Marlowes murder in a hired room near London, the pamphleteer Robert Greene publicly predicted that if the famous gracer of tragedians did not repent his blasphemies, God would soon strike him down. A few days before Marlowe was killed, the spy Richard Baines informed the Queens Privy Council that he was a proselytizing atheist, a counterfeiter, and a consumer of boys and tobacco. Protestant ministers saw Marlowes violent death at an early age as an act of divine vengeance.

This is a book about Marlowes life, his works, and his world. He was born in 1564, when the earth was just beginning to revolve around the sun. In dislodging the world from its fixed place at the centre of the universe, Copernicus bridged the divide between heaven and earth. The individuals physical location no longer corresponded to his metaphysical status vis vis the rest of creation. The radical Italian philosopher Giordano Bruno, who was living in Oxford and London while Marlowe attended Cambridge University, deduced that God pervades the whole world and every part thereof. Hence, matter is an absolutely excellent and divine thing. We need not search for divinity removed from us if we have it near; it is within us more than we ourselves are. Tamburlaine, Marlowes first and most popular hero, expressed the dangerous thrust of the new cosmology. I hold the Fates bound fast in iron chains, he proclaims, And with my hand turn fortunes wheel about (1.2.17374).

Marlowe was a poor boy on scholarship throughout his education. This situation made him keenly aware of the wealth and prestige that he would never have. His peers at university were needy scholars who competed for a dwindling supply of low-paid jobs in the Church of England. Marlowe found a symbol of their predicament in Dr Faustus, the learned magician who sells his soul to the devil in return for twenty-four years of wish-fulfilment. Although Satan agrees to give Dr Faustus whatever he wants, the base-born wizard cannot imagine a way out of his bookish existence. At the climax of Marlowes Dr Faustus, he conjures up Helen of Troy:

Enter Helen.

Was this the face that launched a thousand ships,

And burnt the topless towers of Ilium?

Sweet Helen, make me immortal with a kiss (v.i. 8991)

The apparition of Helen fills the scholars humdrum surroundings with imaginative splendour. He finally gets what he wants: the most beautiful woman in the best book ever written, Homers Iliad. Dr Faustus belief that the answer to his question (Was this the face?) is yes reminds the spectator that this is not that face! From the standpoint of an early modern Christian, what Dr Faustus sees is a succubus a devil who assumes the form of a female in order to work a twofold harm against men, that is, body and soul, so that men may be given to all vices.

The contrast between the heros bookish fantasy life and the exterior world that he is up against gives Dr Faustus a subjective depth that was new to European theatre. A decade later, during the golden age of Spanish drama, the novelist Miguel de Cervantes incorporated this contrast between fantasy and reality into prose fiction. In his novels most famous moment, Cervantes hero Don Quixote charges into a bunch of windmills, imagining that they are evil giants. His squire points out that these are windmills, but the would-be knight remains deluded, explaining that an evil magician has turned these giants into windmills in order to deprive me of the glory of defeating them. Dr Faustus inhabits an older, more supernatural plane of reality than his Spanish contemporary does. The enchanted landscape of Dr Faustus is haunted by demons that expect the audience to believe in them. Where Dr Faustus is possessed, Don Quixote is crazy. Where Dr Faustus comes at the end of a waning tradition of Medieval religious drama, Don Quixote marks the birth of the modern novel.

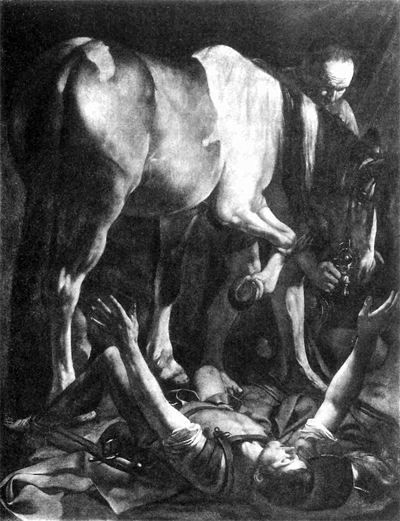

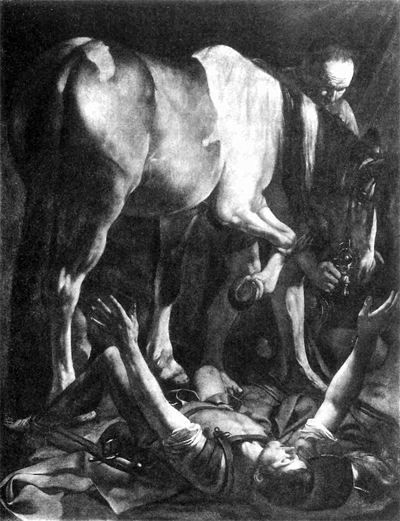

The Church of England trained aspiring scholars to walk not after the flesh, but after the spirit (Romans 1:8). Tamburlaine and Dr Faustus put St Pauls exhortation into reverse gear. Marlowe made the unregenerate flesh come alive on the stage. The same impulse pervades the work of Marlowes younger contemporary Caravaggio. In Caravaggios painting The Conversion of St Paul, Saul of Tarsus, as St Paul was called before his conversion, is journeying to Damascus when suddenly there shined round about him a light from heaven (Acts 9:3). This was the pivotal moment when the Lord transformed the fanatic persecutor of Christians into the zealous advocate of the Christian faith. Caravaggios masterpiece tells a different story. The heavenly light shines from within Sauls massive horse. The horses right leg and shoulder change into a satyr-like body poised above Sauls outstretched arms, extended fingers, and open thighs. These details revivify the flesh that Sauls Biblical prototype relinquishes. Marlowe too conceived of Scriptural events in entirely physical human terms. The core of Marlowes atheism lay in his refusal to read the Bible after the spirit. In taking Scripture literally, he read it after the flesh.