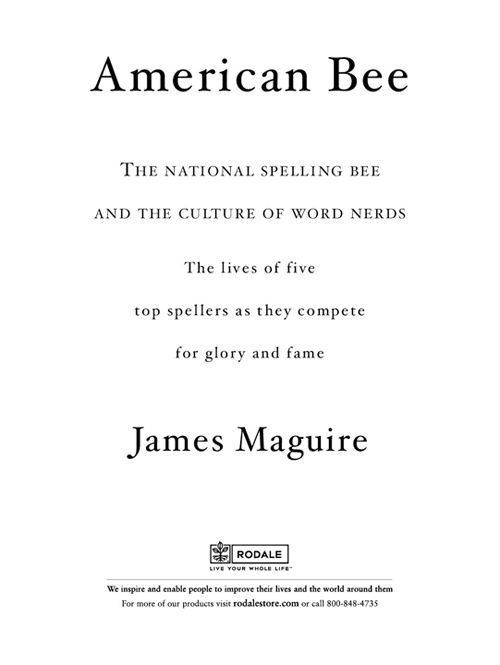

Prologue

As I traveled around the country, talking with the many people I spoke with to report the story of the National Bee, I was often asked: What made you want to write a book about the spelling bee? The question was usually asked with great politeness, but with no small wonder, as if to inquire: Thats an odd topic you have there, fellow. What gives?

Its a reasonable question, and it certainly deserves an answer. I have to confess, though, that I usually gave an abbreviated version of what drew me to the story. To give a full account would have required me to hold forth for several minutes. And at the end of such a lengthy monologue, I feared, some of the questioners might have suggested I sit quietly while they fetch a cool drink of water.

Still, the query calls for a full response, and now is the time. So if youll grant me just a few minutesand yes, I have a glass of cool water at handIll tell you why I feel its important that there be a book about the Bee.

The story of the National Spelling Bee is many stories in one.

Its a sports story of sorts, with all the drama of a high-stakes athletic contest. (In fact, the cable TV channel ESPN broadcasts the Bee alongside sporting events like boxing and basketball.) The contestants win or loseno second chancein real time, onstage in front of a live audience. Each year, from a starting pool of ten million kids, spellers compete their way upward in city and regional bees, hoping to become one of the 275 or so who makes it to Washington. The story of how these 275 finalists find one champion has as much narrative drive, as much sweat and tears and joy, as any football or baseball game. (More so, actuallybut thats just my personal opinion.)

Its a story of pure Americana, part Norman Rockwell, part Horatio Alger. The Bee is an egalitarian gathering in which kids from every social class compete in a true meritocracy. A window washers daughter competes with a bankers son; a first-generation Korean goes toe-to-toe with a Mayflower descendant. Give me your tired, your poor, your huddled masses yearning to breathe free: Every year, the audience is sprinkled with immigrant parents, mothers and fathers who speak in a thick accent, watching their children compete in a second languagethe event, like the arms of Lady Liberty, is open to all. In the most idealistic American tradition, the Bee offers a level playing field, in which color of skin and your last name mean nothing, but hard work and belief in self mean everything.

Its a language story, in which that cultural sponge known as the English language plays a starring role. The top spellers are obsessive etymologists. They are language detectives, exploring lingual patterns, digging into Latin and Greek and French, looking for clues to help them decipher obscure polysyllabics. Spelling, at this level, is about far more than recitation. Its about understanding how the language is built, and how the history of English created this eccentric patchwork called modern spelling. Its about all the skills that further literacy: voracious reading, a sprawling vocabulary, even knowledge of grammar. The Bee is like a yearly Woodstock for the language arts crowd.

First and foremostand here we get to the heart of the Beeits a story about kids, about how the Bees challenges transform them. Or, more accurately, how the kids transform themselves. For these top spellers, the Bee is an odyssey that includes the smaller bees they must win, countless hours of study and drill, and a semi-Olympian process of psych-up. The nerves can be fearsome. Finally, they step to the microphone in front of a mass audience (including parents and television cameras) to face an unknown challenge. Theyre out there all alone, forced to rely upon only their own resources. These moments are like a little pressure cooker. This is necessarily a growth experience, whether or not they spell correctly. And that, really, is what the Bee is all about: young people growing, within the context of a high-profile educational environment. Thats a beautiful thing.

As icing on the cake, its the story of a big party, a yearly gathering of like-minded soulsyoung soulswho, in between competing with each other, share a subculture with its own idiosyncrasies and status symbols. They are word nerds. They study Latin and play video games. They have fantasies of spelling the perfect eight-syllable word. Many of them stop reading only long enough to drill lunarlike morphemes, carrying their laptops outside to play, lugging their dictionaries on family vacations. They are a strange bunch, which makes them an interesting bunch.

In short, the Bee is an invaluable nugget of American life. Despite the odd niche it occupies, it says a lot about who we are, our oddness, our strengths. And, after enduring for hundreds of years, its a folk tradition that can safely claim to be a permanent part of the American scene. The Bee is a story that deserves to be told.

One more thing, on a personal note. As I got to know the spellers and their families I profiled in this book, I had a wonderful time. Having dinner with the families, talking with the spellers, learning about their hopes and their worries, being at the Bee in Washingtonit was a rich experience. I consider myself lucky for having been able to report this story.

If you enjoy reading this book even a fraction as much as I enjoyed writing it, Ill feel as if Ive just spelled rijsttafel in the final rounds of the National Bee. In other words, pretty darn good.

And now, let the spelling begin...

James Maguire

Part

Life at the Bee: The 2004 National Spelling Bee, Washington, DC

There are killer words flying around you all the time, the person on your left or your right takes a bullet, and you get an easy one...

Henry Feldman, 1960 Bee champion

1 The Pressure

David Tidmarsh is breathing like a runaway pony. And no wonder: The slender fourteen-year-old stands onstage facing six judges and a crowded ballroom, with all eyes on him. In the front row sits an Associated Press reporter, dispatching updates to newspapers across the country. Near the stage huddles an ESPN television crew, beaming Davids visage to thousands of viewers. The roving cameraman moves to catch his every grimace; another camera, a crane-operated affair swooping toward the stage, resembles a high-tech dinosaur that might devour Davids 110-pound frame as an afternoon snack. A few feet away, also on the red-carpeted stage, sits his mother; the tape later reveals she has a tear suspended at the edge of her right eye, waiting for her sons next word.

David faces gaminerie, a French word meaning an impudent or roguish spirit. His face, as wide open as the farmland around his hometown of South Bend, Indiana, jogs quickly through a crowd of emotions: fear, hope, pure anxiety, even a short smile. Hes a self-effacing kid, the kind of boy who, when you express amazement at how hard hes studied, replies, Yeah, I guess so. He steps closer to the microphone and we hear his hyperventilating breath. A few audience members even chuckle lightlyhis deep breathing right into the microphone sounds something like Darth Vaders demonic respirationbut the mood in the room is far too close for real laughter.