The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

In memory of my father, Acton Reavill,

who set me on my path in life as a young child, taking me to Al Capones hideout in northern Wisconsin, and to Little Bohemia lodge, where he showed me the bullet holes from John Dillingers shoot-out with the Feds

CONTENTS

What a field day for the heat

S TEPHEN S TILLS

F OR W HAT I T S W ORTH

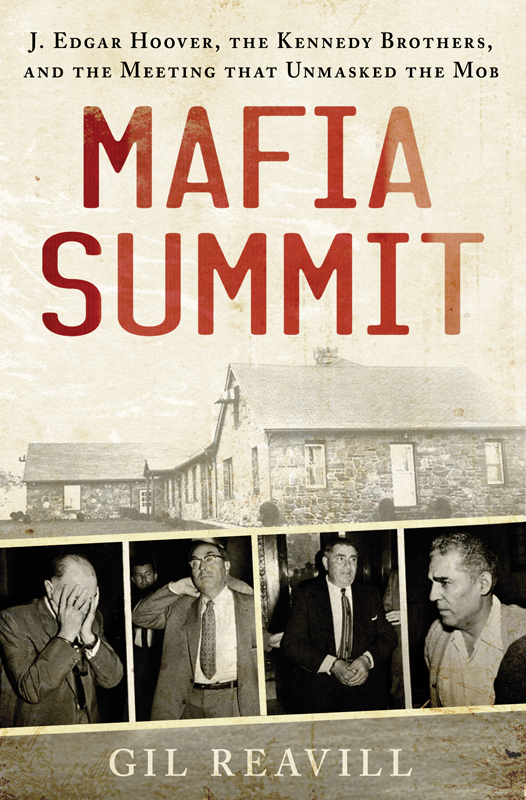

PROLOGUE

McFall Road, Apalachin, New York

O UT OF ALL THE CARS parked alongside McFall Road in the tiny New York hamlet of Apalachin, the Chrysler Crown Imperial limousine stood out. Not just an automobile, but a statement of wealth and prestige, expressed in an ornate chrome grill and a set of sweeping tail fins. A fat, shiny, outlandish vehicle, a perfect signifier for 1950s America.

Midday on a foggy, rainy Thursday, November 14, 1957. Through his field glasses from fifty yards away, Sergeant Edgar Croswell of the New York State Police surveilled not only the big Imperial, but also a dozen similar late-model land boats around it, as well as the hilltop estate where they were parked.

Sergeant Croswell always had a sharp eye for cars. When his youngest son Bob was a child, Croswell taught him to recognize automobiles as a kind of parlor tricka six-year-old able to nail the difference between a Ford Custom, say, and a Galaxie, rattling off the make, model, and year like a savant.

Back in the 1920s, Walter Chrysler founded the Imperial line to compete with GMs Cadillac and Fords Lincoln. Though it never quite measured up, selling only a single car for every ten Cadillacs, the model had its adherents. In later days, the Imperial found itself banned from demolition derbies, its X-frame construction so solid that it was virtually unbeatable.

The forty-four-year-old Croswell drove a Buick himself, but the Imperial sparked his interest. The current-years model, brand spanking new. The big sedan took its place among a whole fleet of Caddies and Continentals and Lincoln Premieres, parked in the spacious driveway lot in front of a four-bay garage, left alongside the road or pulled into a field next to a rustic fieldstone ranch house.

With Croswell that day were his state police partner, Trooper Vincent R. Vasisko, and a pair of revenue agents from Treasurys Alcohol and Tobacco Tax Unit, Art Ruston and Ken Brown.

Croswell turned to his cohorts and ticked off the state plates visible from his post.

New Jersey, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, New York, New York, Ohio, Illinois, he said. Some of the license plates, he noticed, had special low numbers, usually indicating owners of influence.

Those arent salesmen cars, Vasisko said.

No, Croswell said. Lets get the numbers down as fast as we can.

The lawmen moved forward, taking plate numbers. Lots of cars, but no people. The driveway, yards, and fields around the compound appeared curiously devoid of life. Where was everybody?

The fieldstone house on McFall Roadreally a collection of buildings, a compound of sorts, with a main residence, a summer pavilion, a garage, and outbuildingsbelonged to Joseph Barbara Sr., who presented himself to the world as an upstanding citizen, the area distributor for the lucrative Canada Dry line of beverage products.

But Joseph Barbara defined the old police term hinky. Croswell knew Barbara had been buying up sugarmassive amounts, really, 30,000 pounds a month for the past year. That much sugar meant illegal stills.

Counterintuitive as it was, moonshining had not ended with Prohibition. By avoiding excise taxes, illicit alcohol production could prove enormously lucrative, not as golden as it had been during the Volstead Act, but even so a steady earner.

Unsure exactly what was going on at the McFall Road estate, but thinking it might have something to do with moonshining, Croswell called in the revenuers.

Sergeant Croswell served as a senior investigator with the BCI, the Bureau of Criminal Investigation, which was the State Police equivalent of a detective bureau. Over a decade previous, during World War II, upon his first encounter with Joe Barbara, Croswell opened a mental file on the man, the informal kind of data-set all lawmen keep continually up-to-date, on the hinkiness of whatever kind that crops up within their territory.

Every once in a while, at least a couple times a month, Croswell would drive up to Barbaras impressive Apalachin compound, ten miles west of Binghamton. His personally motivated ten-year surveillance campaign, wholly unmandated by his superiors in the State Police, had come to this: a single cruiser parked at the property line of the Barbara estate, near a driveway parked thick with expensive limousines that, by all rights of logic and cop intuition, should not have been anywhere near backwoods Southern Tier New York.

The squadron of big cars, bespeaking power and privilege, ranged against the single unmarked police car with its force of four. Croswell started to feel a little lonely up there on top of the hill. He made an executive decision, got on his radio, and put the word out to his fellow state police.

Black-and-whites began pulling out of barracks in Binghamton and the neighboring towns of Waverly and Horseheads, cutting off the approaches to Apalachin. In all, seventeen additional troopers answered the call, men Croswell had worked with often before, their names readily familiar to him: Lieutenant Kenneth Weidenborner, Sergeant Joseph Benenati, Trooper Joseph D. Smith, Trooper Richard C. Geer, Trooper Howard Teneyck.

The state police threw a net around the Barbara estate, cutting off not only McFall Road but also East River Road to the north, McFadden Road to the west, Pennsylvania Avenue to the east, and Rhodes Road to the south. Whoever or whatever was there at Barbarasmoonshiners, or something more sinisterwas boxed in, with cops blocking any and all possible exit ways from the area.

Croswell hoped he was right in alerting the troops. All he had to go on was a homeowners extensive arrest record, a strangely out-of-place collection of big cars, and a few other indications that some sort of illicit gathering was going down on McFall Road.

A fish truck emerged from the Barbara place and rattled up the road. The quartet of lawmen let it pass. The driver, local merchant Bartolo Guccia, had just taken an order for three pounds of porgies and a pound of mackerel at the kitchen of the big stone house. Guccia, a sallow little man with an old-world Italian accent, proceeded past the cops, but then pulled up and came back. He waved jauntily at Croswell and Vasisko and returned to the Barbara compound.

Almost at the same moment, a crew of a dozen men in sharp suits (fourteen-karat hoodlums, Croswell mentally tagged them, like a collection of George Rafts) rounded the corner of the screened-in summer pavilion on the Barbara estate. As though they were cartoon characters, the men stopped comically short upon seeing the staties taking down plate numbers along the road.

Cops and quarry eyed each other, the same thought occurring to both groups: who were these guys?

Through the binoculars, Croswell noted the heavy gold watches on almost every mans wrist. He could pick out their diamond jewelry, rings, stickpins, and studs, sparkling in the washed-out light of the autumn noon.