CONTENTS

About the Book

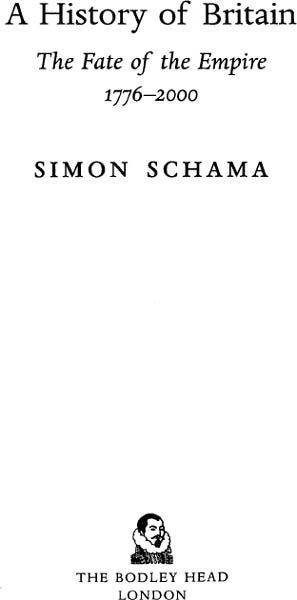

While Britain was losing an empire, it was finding itself The compelling opening words to The Fate of the Empire , set the tone and agenda for the final stage of Simon Schama's epic voyage around Britain, her people and her past. Spanning two centuries, crossing the breadth of the empire and covering a vast expanse of topics from the birth of feminism to the fate of freedom he explores the forces that shaped British culture and character from 1776 to 2000.

The story opens on the eve of a bloody revolution, but not a British one. The French Revolution never quite crossed the Channel, though its spirit of fiery defiance and Romantic idealism did, sparking off a round of radical revolts and reforms that gathered momentum over the coming century from the Irish Rebellion to the Chartist Petition. The great question of the Victorian century was how the worlds first industrial society could come through its growing pains without falling apart in social and political conflict. Would the machine age destroy or strengthen the institutions that held Britain together, from the family to the farm? And if the British Empire helped to make Britain stable and rich, did it live up to its promise to help the ruled as well as the rulers? On the way to answering these questions, The Fate of the Empire makes stops at both celebrations, like the Great Exhibition, and catastrophes, like the Irish potato famine and the Indian Mutiny. Amidst the military and economic shocks and traumas of the 20th century, and through the voices of Churchill, Orwell and H. G. Wells, it asks the question that is still with us is the immense weight of our history a blessing or a curse, a gift or a millstone around the neck of our future?

It is a vast compelling epic, made more so by the lively storytelling and big bold characters at the heart of the action. But alongside flamboyant heroes, like Nelson and Churchill, Schama recalls unsung heroines and virtually unknown enemies. Alongside the grand ideas, he exposes the grand illusions that cost untold lives. Schama looks head on at the facts and asks, What went wrong with the liberal dream? The answers emerge in The Fate of the Empire , which reveals the living ideals of Britains long history, a history that tied together social justice with bloody-minded liberty.

About the Author

Simon Schama is University Professor of Art History and History at Columbia University and the prize-winning author of fourteen books, which have been translated into twenty languages. They include The Embarrassment of Riches: An Interpretation of Dutch Culture in the Golden Age; Citizens: A Chronicle of the French Revolution; Landscape and Memory; Rembrandts Eyes ; the History of Britain trilogy and Rough Crossings , which won the National Book Critics Circle Award. He has written widely on music, art, politics and food for the Guardian, Vogue and the New Yorker . His award-winning television work as writer and presenter for the BBC stretches over two decades and includes the fifteen-part A History of Britain and the eight-part, Emmy-winning Power of Art. The American Future: A History appeared on BBC2 in autumn 2008.

PREFACE

READERS IN SEARCH of an exhaustive account of the careers of Sir Robert Peel or Reginald Maudling should put this book down right now. For, with this last volume of A History of Britain , it will be more than ever obvious that the cautionary indefinite article in the title is truly warranted, both in terms of the frankly interpretative reading of modern British history offered, and in the necessarily subjective judgements I have made about which themes to explore in most detail. As with the BBC2 television programmes, I have opted to concentrate on a smaller number of stories and arguments, but to treat them in detail rather than give equally cursory attention to everything bearing on the transformation of Britain into an industrial empire. As with the two previous volumes, this book gives space to many themes which could not be accommodated within the iron narrative discipline of the television hour. But even this does not mean there is any pretence at all to comprehensiveness. No one will be in any danger of confusing The Fate of Empire with a textbook. The last half of the 20th century is deliberately treated with essay-like breadth and looseness partly, at least, because I have trouble treating any period contemporary with my own life as history at all (an illusion, no doubt, of the passing of years). As the title of this volume suggests, however, I have tried to do something not always ventured in histories of 19th- and 20th-century Britain: to bring together imperial and domestic history, trying at all times to look at the importance that India, in particular, had for Britains expansive prosperity and power, and at the responsibility that the Raj had for Indias and Irelands plight.

New York, 2002

And out you come at last with the sun behind you into the eastern sea. You speed up and tear the oily water louder and faster, sirroo, sirrooswishsirroo, and the hills of Kent over which I once fled from the Christian teachings of Nicodemus Frapp fall away on the right hand and Essex on the left. They fall away and vanish into blue haze; and the tall slow ships behind the tugs, scarce moving ships and wallowing sturdy tugs are all wrought of wet gold as one goes frothing by. They stand out bound on strange missions of life and death, to the killing of men in unfamiliar lands. And now behind us is blue mystery and the phantom flash of unseen lights, and presently even these are gone and I and my destroyer tear out to the unknown across a great grey space. We tear into the great spaces of the future and the turbines fall to talking in unfamiliar tongues. Out to the open we go, to windy freedom and trackless ways. Light after light goes down. England and the Kingdom, Britain and the Empire, the old prides and the old devotions, glide abeam, astern, sink down upon the horizon, pass pass. The river passes London passes, England passes

H.G. WELLS, Tono-Bungay (1909)

the country houses will be turned into holiday camps, the Eton and Harrow match will be forgotten, but England will still be England, an everlasting animal stretching into the future and the past and, like all living things, having the power to change out of recognition and yet remain the same

GEORGE ORWELL, England Your England (1941)

CHAPTER

1

FORCES OF NATURE:

THE ROAD TO

REVOLUTION?

WHILE BRITAIN WAS losing an empire it was finding itself. As redcoats were facing angry crowds and hostile militiamen in Massachusetts, Thomas Pennant, a Flintshire gentleman and naturalist, set off on his travels in rough Albion in search of that almost extinct species: the authentic natural-born Briton. Amidst the upland crags and chilly tarns of Merionedd, he thought he had discovered them: Britains very own home-grown noble savages, the descendants of the earliest tribes, whose simplicity had survived, somehow, the onslaught of modern civilization. At Llyn Irdinn he walked round two circles of standing stones, which he believed were undoubtedly the remains of druidical antiquities. Nearby, he discovered the human equivalent, at the house of Evan Llwd, where Pennant was treated to hospitality in the style of an antient Briton with potent beer to wash down the Coch yr Wdre or hung goat and the cheese compounded of the milk of cow and sheep. He likewise showed us the antient family cup made of a bulls scrotum in which large libation had been made in days of yore Here they have lived for generations without bettering or lessening their income, without noisy fame, but without any of its embittering attendants.

Next page