Dick Couch, George Galdorisi, Tom Clancy (Series Creator), Steve Pieczenik (Series Creator)

Out of the Ashes

Decades ago, Winston Churchill famously said, We sleep safely at night because rough men stand ready to visit violence on those who would harm us. More contemporaneously, in the 1992 film, A Few Good Men, in the courtroom dialogue, Colonel Nathan Jessup (Jack Nicholson) responds to an aggressive interrogation by Lieutenant Daniel Kaffee (Tom Cruise) with, We live in a world that has walls, and those walls have to be guarded by men with guns Because deep down in places you dont talk about at parties, you want me on that wall. You need me on that wall.

This book is dedicated to the selfless men and women in and out of the military who toil and sacrifice in obscurity so we may sleep safely at night. They receive no medals or public recognition, and few know of their risks, dedication, and contributions to our security. They endure lengthy and repeated deployments away from their families. Yet they stand guard on the wall for all of us, silently, professionally, and with no acclaim.

In 1996, then-first lady Hillary Clinton wrote the book It Takes a Village. Reviving Tom Clancys Op-Center series was a momentous undertaking and it took a village of family, friends, colleagues, and others we reached out to in order to make Out of the Ashes a book that could live up to our expectations and especially to the expectations of readers of the twelve previous Op-Center books as well as our new Op-Center readers. Many thanks to the following who contributed their time and talent so unselfishly: Bill Bleich, Anne Clifford, Ken Curtis, Melinda Day, Jeff Edwards, Herb Gilliland, Kate Green, Kevin Green, Krystee Kott, Robert Masello, Laurie McCord, Scott McCord, Rick Ozzie Nelson, Bob ODonnell, Jerry ODonnell, Norman Polmar, Curtis Shaub, Scott Truver, Sandy Wetzel-Smith, and Ed Whitman.

Additionally, Out of the Ashes would not have been possible nor would it have been produced so professionally without the expertise and persistence of our agent, John Silbersack, our editor, Charlie Spicer, as well as Mel Berger, Robert Gottlieb, Madeleine Morrel, April Osborn, Matthew Shear, and Anna Wu.

The Muslim East and the Christian West have been at war for over a millennium. They are at war today, and that is not likely to change in the near future. As Samuel Huffington would put it, the cultures will continue to clash. At times in the past, the war has been invasive, as in the eighth century, when the Moors moved north and west into Europe, and during the Crusades, when the Christian West invaded the Levant. Regional empires rose and fell through the Middle Ages, and while the Renaissance brought significant material and cultural advances to the Western world, plagues and corrupt monarchies did more to the detriment of both East and West than they were able to do to each other.

In time, as a century of war engulfed Europe and as those same nations embarked on more aggressive colonialism, the East-West struggle receded into the background. The nineteenth-century rise of nationalism and modern weapons technology in the West resulted in an almost universal hegemony, while the East remained locked in antiquity and internal struggle. The twentieth century and the developing thirst for oil were to change all that.

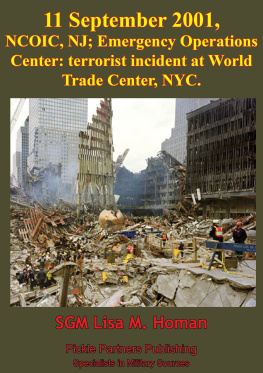

The seeds of todays East-West conflict were sown when Western nations took it upon themselves to draw national boundaries in the Middle East after the First World War. The infamous Sykes-Picot agreement, which clumsily divided the Middle East into British and French spheres of influence, created weak-sister countries such as Syria, Iraq, and Lebanon, all but ensuring permanent turmoil. After the Second World War, Pan-Arab nationalism, the establishment of the state of Israel, the Suez crisis, the Lebanese civil war, and the Iranian revolution all drove tensions between East and West even higher. While the competition for oil and oil reserves remained a major stimulus, long-standing Muslim-Christian, East-West issues created a catalyst that never let tensions get too far below the surface and then came 9/11.

The events of September 11, 2001, and the retaliatory invasions that followed, redefined and codified this long-running conflict. For the first time in centuries, the East had struck at the West, and delivered a telling blow. Thus, from Afghanistan to Iraq to Yemen to North Africa and into Indonesia, Thailand, the Philippines, and beyond, the struggle has now become worldwide, nasty, and unrelenting.

Surveys taken just after 9/11 showed that some 15 percent of the worlds over 1.5 billion Muslims supported the attack. It was about time we struck back against those arrogant infidels, they said. A significant percentage felt no sympathy for the Americans killed in the attack. Nearly all applauded the daring and audacity of the attackers. Many Arab youths wanted to be like those who had so boldly struck at the West.

As the worlds foremost authority on the region, Bernard Lewis, has put it, the outcome of the struggle in the Middle East is still far from clear. For this reason, we chose the Greater Levant as the epicenter of our story of Op-Centers reemergence.

Dick Couch

George Galdorisi

Ketchum, Idaho

Coronado, California

Long before the events of 9/11, even before the first attack on the World Trade Center, America has been under siege by the dark forces of terrorism. Radical Islam, technology, and repressive regimes in oil-rich nations had encouraged the disenfranchised to seek new and more deadly ways to bring harm to our nation. The attacks of 9/11 demonstrated to the world that America was vulnerable. However, in response to those attacks, an aroused America proved it could strike back.

The incursions into Iraq and Afghanistan, while only modestly successful in stabilizing those nations, took a fearful toll on the senior leadership of al Qaeda and their franchises around the world. The worlds most formidable terrorist group was decimated to the extent that Americans began to look at the attacks on New York and the Pentagon as a one-time event. Such an attack on our soil had not taken place before, and it hadnt happened since. Perhaps those trillions of dollars spent in the Global War on Terrorism had not been wasted after all. The U.S. military and intelligence communities could rightfully take credit for pushing the terrorists back into the shadows, but there had been another force at work one that operated in the shadows as well.

Before 9/11 and for several years afterward, our nation was protected by a quiet, covert force known as the National Crisis Management Center. More commonly known as Op-Center, this silent, secret mantle guarded the American people and thwarted numerous threats to our security. The charter of Op-Center was unlike any other in the history of the United States, and its director, Paul Hood, reported directly to the president.

Op-Center dealt with both domestic and international crises. What had started as an information clearinghouse with SWAT capabilities had evolved into an independent organization with the singular capacity to monitor, initiate, and manage operations worldwide. They were good; in fact, too good. Budgets were tight and cuts had to be made. There also was the vaunted U.S. Special Operations Command to deal with terrorists. So Op-Center was disbanded, but the need for Op-Center remained.

For America in the second decade of the twenty-first century, Op-Center was becoming little more than an increasingly distant memory and even those who had taken issue with Op-Centers disestablishment were finally moving on. However, the nation was about to learn just how dangerous it was to do away with this valuable force and the awful price it was about to pay. Just how much Op-Center was needed was about to be demonstrated.