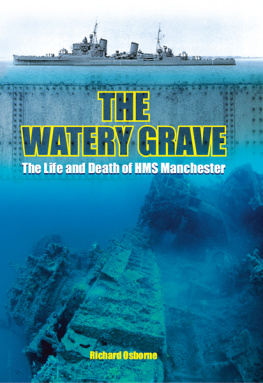

Bruce Alexander - Watery Grave

Here you can read online Bruce Alexander - Watery Grave full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 1996, publisher: Putnam, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Watery Grave

- Author:

- Publisher:Putnam

- Genre:

- Year:1996

- ISBN:9780399141553

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Watery Grave: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Watery Grave" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Watery Grave — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Watery Grave" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Bruce Alexander

Watery Grave

A NOTE TO THE READER

If you would be so good as to put your mind to it, you might try to imagine a storm at sea. Yet perhaps, reader, I ask too much, for unless you are a veteran of many voyages and have endured consequent dangers of fierce weather on shipboard, you could not conceive of such a storm as this one, which many an experienced seaman claimed to be the worst he had known.

The sky in mid-afternoon is darkened by clouds so that it be as deep night. From those clouds pours a rain which, though constant, is unsteady, for it often comes in great rushes near drowning the sea itself, then slacks in intensity for minutes at a time, only to explode once again in vast inundations of wet. The waters of the sea rise and fall in mountain-sized swells so that a ship of good size, a frigate of the Royal Navy, is tossed up and down, to and fro, like some small button box with sails.

Aboard that frigate, those of the crew on deck struggle to do what they can to keep the ship afloat. It slides precipitously down to the bottom of wave after wave to crash at the bottom, often taking on water, laying about port and starboard in the trough and taking on more water still. Those of the crew below-decks pray, curse, and stay close to the ladders that they may not be last to the boats should the ship begin to break apart.

Into this hellish scape two figures appear upon the poop deck, which, as the ships uppermost level, is in such circumstances also its most perilous point. Having emerged from below, they make their way slowly across the windswept space. Only one of them proceeds under his own power; he supports the other, who, though his feet touch the deck, can hardly be said to be walking at all. The two move

most uncertainly. He who bears the load of the other goes stiff-legged with the weight of him.

Thus slowly they make their way across the poop deck to the starboard ladder. But in the midst of their journey the frigate drops low into the trough of a deep swell, and the weaker of the two is torn from the grasp of the stronger. He is thrown against the taffrail just opposite the starboard ladder. Quite miraculously he keeps his feet but not for long. His companion extends his arms and the other man disappears overboard.

That fmal movement is seen by two men on the quarterdeck below. The first, who stands wrestling with the helm, glances across at the crucial moment and perceives it as a futile attempt to hold the doomed man back. The second, holding tight to the stout rope which secures a cannon in place, later describes it as the fmal push which sends the unfortunate to his watery grave.

Rescuer or murderer? That question would occupy us profoundly in time to come. And even to this day, this question of intent remains matter for heated discussion, even bitter argument among those many whose lives it touched.

ONE

On a day in July 1769, I had been sent by Sir John Fielding to accompany Lady Fielding to the Tower Wharf, where we were to meet her homecoming son, Tom, returned from near three years duty on the India station. I had been told by Sir John that the official welcome ceremonies for the H.M.S. Achenttire were not to begin until noon, and our departure from Bow Street left ample time for a prompt arrival. Yet the hour precluded the possibility that Sir John might have attended the occasion, as he would have liked, for he must sit his court in Bow Street that day, as he did every day, barring sickness or some unforeseen occasion. Therefore had he taken me aside, given me a proper allowance of shillings and pence, and charged me to convey Lady Fielding to the Tower Wharf and, with her son, back again to Bow Street. It was a considerable responsibility for a fourteen-year-old boy, as I was then, yet I was grown a pair of inches in the past year and was the size of a smallish man.

As we descended Tower Hill, the driver of our hackney carriage reined in with a call of command to the horses. This is as far as I can take you, called he to us. You take the footbridge yonder. He pointed ahead. Cross it and up the stairs, and you will be at the bottom of Tower Wharf.

And thus we proceeded, the moat on our left, in the direction of the Thames, down to the bottom of Tower Hill. It seemed certain to me that we were in no wise tardy for the proceedings. Yet just then, with a great roll of drums, a tootling of fifes, and a call of the clarion trumpets, an invisible band struck up beyond the stairs and Lady Fielding shot ahead and disappeared up the staircase. By the time I caught her

up, she had joined the crowd on the wharf and was pushing into it like any Covent Garden housewife at the greengrocers stall.

There, above the hubbub and shouting, the band which had assembled only ten paces or so across the cordoned open space before us made an even greater din. There, too, near the front of the crowd, I had my best view of the Thames. As I now recall, I had some dim notion that the H.M.S. Adventure would be firmly docked at Tower Wharf, side by side with it. Yet it was not so. It lay tar out at anchor some distance up the river, sails furled, pennants flying. The reason for this was evident. The ship was surely too big to fit the wharf. As I learned later, it was also the custom for ships of war to maintain a discreet distance from the shore. A frigate the Adventure was, as I had heard. I knew there were bigger vessels in His Majestys Navy, yet I could not, for the life of me, imagine such.

A boat of good size, manned by eight oarsmen, had set forth from the frigate. There were many more within the boat, so many in fact that the men at the oars made slow progress toward the wharf.

Oh, Jeremy, said Lady Fielding by my side, what shall I do if I do not recognize him? He was but a boy when he left. Now, by his letters at least, he seems a man.

Surely a mother will know. It seemed the right thing to say.

She considered that a moment, then gave a firm nod. Yes, said she, surely.

The boat had disappeared beneath the height of the wharf. I expected its passengers to pop up at an moment. Yet first there was a courtesy to be observed. I heard a voice boom forth from the river below.

Permission to come ashore.

A man in uniform stepped forward on the wharf and, in lieu of words, he responded with a long blast in several notes on a whistle.

Then, after a pause, crew members of the H.M.S. Adventure appeared from below. I supposed they had come up a ladder. The crowd applauded at the appearance of each mariner and indeed that seemed appropriate, for there was something theatrical in all this. As the men came, one by one, they formed a ragged line along the wharf. By the time they had all assembled, they were fifteen in number. Once there together, standing in the same stiff attitude, they were forced to wait as a stout man of senior years came forward and stood before them.

He made a speech of some minutes duration. By throwing his voice back and forth, he managed to address both the seamen and the crowd that had come to welcome them. He was richly dressed in uniform, bemedaled, beribboned, and red of face. Without knowing his rank, I judged him to be a rear admiral at least. The speech he gave, though in no wise memorable, praised the men before him for keeping the trade routes open against attacks by pirates and privateers. He cited some twenty-odd separate engagements in which the officers and men of the H.M.S. Adventure had acquitted themselves admirabl prizes taken, trade tonnage saved, and so on. All this was quite beyond me, as I believe it was to most of us there. Yet he continued and here he addressed members of the crew only, commending them for remaining firm in their duty in the face of apparent dissension in the upper ranks and reports of violent attack.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Watery Grave»

Look at similar books to Watery Grave. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Watery Grave and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.