PREFACE

This book came about because Id written another, earlier book about Philip Whalena journal of life with him at Zen Center, modeled roughly on Boswells chronicles of Samuel Johnson. Through recording as accurately as I could Philips conversations and describing the places these occurred, I hoped to... actually I had no real goals beyond the pleasure and practice of writing. I just wanted to be writing something, and here was Philip, an accomplished author, an eccentric, whose presencelarge body, distinctive voice, and peculiar, learned insightshad provoked many in his company to write about him. At least two other young men, both more-or-less practicing Buddhists, had, at different times, kept exactly the same kind of journal I did. The title of this biography comes from a remark Philip made to one of those writersSteve Silbermanin a hardware store. Steve wrote it down in his journal. None of us knew about the others work until years later. Wed all clearly felt, during the time of our writing, that something unusual and valuable was happening in front of our eyes. Philip Whalen was happening.

Shortly before Philips death in 2002twenty years after Id written my journalI typed it up. Who knows how these things work, but Id been roused from distraction and laziness to this concentrated labor by a powerful dream visit from Philip. In the dream, he wondered if we might not lose all those texts we worked on. At the time, he lay in a hospice in San Francisco, nine thousand kilometers from Cologne, where I was working. Typing for those weeks, I may have been unconsciously trying to hold him with old stories.

A respectful time after his death, I sent the journal, titled Side Effect, to a few likely publishers. They all kindly assured me that theyd enjoyed reading it very much, but that in todays market, well, Philip wasnt famous enough, and neither was I, and how could they sell it? Even five years earlier they could have, but these days.... Shortly after this, though, University of California Press, in the person of my wonderful editor, Reed Malcolm, got in touch about doing the biography.

In the twelve years we practiced Buddhism together in Zen Centers three locationsas well as in the eighteen years after that, when we stayed in touch and continued practicing, sometimes in different traditions, sometimes from different countriesPhilip taught constantly. He taught official courses in literature, he taught courses in Buddhist theory and history, he taught a select few what he could about poetry. But this is not what I mean by he taught. The group of young people, mostly men, who gathered around Philip wherever he was definitely felt they were learning something from him, even if they were not actively studying. It was and remains a puzzle to name that topic: it wasnt literature exactly; it wasnt recent or ancient history; it wasnt how to be a Zen student or a friend, or how to relate to celebrities; it wasnt how to look at paintings, how to listen to music, how to cook and enjoy food; it wasnt how to speak, how to read, or how to open the mind. But it wasnt separate from those things, either. They were all very much included.

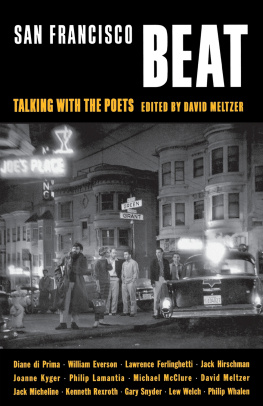

The thought of Philips biography scared me; Id written one and knew how much work they were. That biography was of a remarkable and kind personIssan Dorseybut a person largely unknown to the public, apart from certain local sectors of the gay community. Philip, though not famous, was certainly well known among poets internationally, and among those who cared about the Beat writers. (As one of his circle unkindly put it to him, Youre a name, not a face.) Philip had also left a wide paper trail. Whereas Issan read very little and wrote even less, Philip read and wrote constantly. He kept a journal, and he often wrote several beautiful letters per day. Many of these were squirreled away in the special collections of libraries scattered around North America. They were there because a number of Philips friends were famous writers. The letters these friends had written back were mostly at the University of California Berkeleys Bancroft Library. I was happily anchored in Germany by a two-year-old daughter and a demanding job. Undecided and uneasy, I consulted a Tibetan lama skilled in divination. Word came back that it would be good to undertake the biography. The prophecy also said it could take a long time, and that that would be fine.

The Philip I knew was of course a poet, but that was not his most important aspect. A number of his publications appeared between 1972 and 2002. He would sign these if you asked; you could recognize in the poems people and places belonging to Zen Center. But no matter how strange or beautiful the lines were, they made faint impression compared with the living person handing you back a newly decorated book or broadside.

What relationship does anyones biography have to do with what they wrote? Philip abruptly posed this question to a class he was teaching in late July 1980, at Naropa University. He observed, The person of the poet is often extremely difficult and unpleasant.... I can distinctly remember Kenneth Rexroth saying, Writers are terrible people. You dont want them in your house! He says this to a roomful of writers he was accustomed to seeing on Friday evenings.

Because Philip and the class had been studying Hart Cranes work that afternoon, he allowed that Brom Webers biography of Crane, though a cranky book, related the facts of the life well enough and might be useful in getting at the poems. The earlier Horton biography had necessarily left out a lotCranes mother was still aliveand the John Unterecker biography, at nearly eight hundred pages, could tell you practically what Crane had been doing on any given day, but it does not help much. You dont read Crane any better, I dont think. Philip was even less encouraging about the two-volume biography of William Faulkner, by Professor Whats-His-Name, as it completely left out an important and obvious love affairand he savaged one of the Hemingway biographies (discussing two others in the process) for extrapolating and romanticizing what Hemingway thoughteven, for example, as he put the barrel of a shotgun in his mouth to kill himself. A contemporary two-volume Emily Dickinson biography received Philips praise for its appendices and scholarly apparatuses, but he complained about the number of salacious detailsthe most incredible tittle-tattleof nineteenth-century Amherst. He was relating these with evident pleasure to the class when he suddenly interrupted himself to exclaim: It does not explain how Emily Dickinson was simply a genius who wrote beautiful poetry!