DAVID WRIGHT - The Canterbury Tales

Here you can read online DAVID WRIGHT - The Canterbury Tales full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2011, publisher: Oxford University Press, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

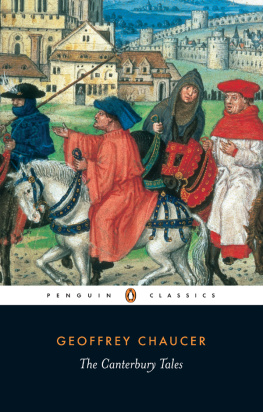

- Book:The Canterbury Tales

- Author:

- Publisher:Oxford University Press

- Genre:

- Year:2011

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Canterbury Tales: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The Canterbury Tales" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

The Canterbury Tales — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "The Canterbury Tales" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Although Chaucer has a knack for providing just the descriptive detail that will individualize each pilgrim, they are almost never identified by anything other than their profession, and they seem, in most ways, to derive their entire world view from the position in society given them by the work they do. They also often (although not always) manifest their personalities in the tales they tell, and the simple plan of the Canterbury Tales, proposed by the proprietor of the Tabard (the Host), is that each pilgrim will entertain his companions by telling two tales on the journey to Canterbury and two on the way back, and whoever is judged to have told the best tale (which the Host defines as the most pleasing and informative) will be treated to a meal by all the other pilgrims. This form, sometimes called a frame-tale because it uses one story (the pilgrimage) to frame others (the tales each pilgrim tells), was not invented by Chaucer, but he makes his frame unusually organic and vivid. The Canterbury Tales collects an enormous variety of narratives (romance, bawdy comedy, beast fable, learned debate, saints life, parable, Eastern adventure), and, given Chaucers great ambition, and the length of time over which the individual tales were written, it is not surprising that they are of uneven quality. And yet part of their richness is to provide something for almost every kind of reader (it is markedly the case that the poems that were most popular in the centuries after Chaucer are the least popular with students and scholars now). The great majority of the Tales are extraordinary however, by turns elaborately ornamented and elegant in their language, movingly passionate in their sentiment, or precise in the minutiae of their observation and comic timing.

At their very best, however, what is most characteristic of Chaucers style and language is the tendency for every aspect of its artfulness to melt away, with the result that all that has been elaborately constructedalmost in direct proportion to the care of that constructionappears so natural as to be real and so familiar as to be always and simply true.

But the converse is not true, since his poetry was often addressed to public men of great power. And, while Chaucer performed the variety of tasks normal for a courtier (serving in attendance at large functions; ferrying letters and money; taking part in military campaigns), it is clear that he was also particularly successful in the creation of the short and long poems whose recitation was a central court entertainment. Chaucer clearly wanted to be around powerful aristocrats, but much of his success in their company was surely due to the fact that he wrote such pleasing poetry that they liked to have him around too. Despite the quality of his connections, Chaucer was, essentially, a civil servant. As he suggests in The House of Fame (c. 1380), much of the reading that informed his poetryand presumably the writing of that poetry as welloccurred late in the evening, after a long days work.

Although Chaucer had an excellent early literary education, in a day when the majority of people were illiterate, that education also qualified him to read and write in much more utilitarian ways. In trips to Genoa and Florence in 1372 and Lombardy in 1378, Chaucers knowledge of Latin (then the international language in the West) was doubtless the qualifying skill for the diplomacy that was his mission. As Controller of Customs from 1374 he was responsible for keeping accurate records of the various payments of the export duty on wool, one of Englands most important tax revenues. As Clerk of the Kings Works from 1389 he would have sent letters in a variety of directions to maintain the kings properties for which he was responsible. His steady progress through these positions suggests that Chaucer was as able a bureaucrat as he was a poet, but it may be, again, that the two skills were not unrelated. Chaucers earliest major poem, The Book of the Duchess (1369), is a daring attempt to console John of Gaunt, one of the most powerful men in England, on the anniversary of his muchbeloved wifes death.

It must have been perfectly judged since Chaucer benefited from Gaunts patronage long afterwards. But to collect hefty taxes from men more powerful than yourself, or to bring disappointing or expensive news about building works to your king, required no less expressive precision than writing such a poem, and Chaucer was clearly as good with the tactful approach in the delicate situation as he was with the well-turned phrase. Chaucer also survived some of the greatest civil and social tumult that medieval England ever saw. The rising of a group of commoners against what they perceived to be an unjust tax in 1381, and their rampage through London, was only the most concentrated moment of violence in a very unstable set of decades which saw a boy ascend the throne in 1377 (Richard II, aged 10), groups of powerful lords attempt to usurp his power by putting his favourites to death (in the Merciless Parliament of 1388), and, finally, the deposition of Richard in 1399. Through it all, disagreement and serious in-fighting in London among various factions resulted in the death of at least one writer, Thomas Usk (beheaded in 1388). Chaucers skill as a bureaucrat need not have seen him through all of these changes, and it is clear that at certain moments of his careerparticularly in the period 13869, when he seems to have left Londonhe was simply prudent enough to move, smartly, out of harms way.

Chaucer can also be seen using his literary skills to navigate his way through very troubled waters. The poem usually called Chaucers Complaint to His Purse is a short allegory, written in the dangerous moment just after Richard IIs deposition, in which Chaucer is bold enough to address complaints about his finances to the new king Henry IV. He must have got the timing and the tone just right again, for the annuity Richard had been paying him is paid as usual the following June. The work Chaucer did to earn his living and the politics he lived through affected what he wrote deeply, but it is the books that Chaucer encountered along the way that shaped his poetry most of all. The six short texts that comprise the basic curriculum for beginning students (the collections of proverbs, beast fables, mini-epics, and elegies that made up what is sometimes called the

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «The Canterbury Tales»

Look at similar books to The Canterbury Tales. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book The Canterbury Tales and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.