M. K. Gandhi, Attorney at Law

The publisher gratefully acknowledges the generous support of the General Endowment Fund of the University of California Press Foundation.

M. K. Gandhi,

Attorney at Law

THE MAN BEFORE THE MAHATMA

Charles R. DiSalvo

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS

BERKELEYLOS ANGELESLONDON

University of California Press, one of the most distinguished university presses in the United States, enriches lives around the world by advancing scholarship in the humanities, social sciences, and natural sciences. Its activities are supported by the UC Press Foundation and by philanthropic contributions from individuals and institutions. For more information, visit www.ucpress.edu.

University of California Press

Berkeley and Los Angeles, California

University of California Press, Ltd.

London, England

2013 by Charles R. DiSalvo

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

DiSalvo, Charles R., 1948.

M.K. Gandhi, attorney at law : the man before the Mahatma / Charles R. DiSalvo.

p.cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-520-28015-1 (cloth : alk. paper)

eISBN 978-0-520-95662-9

1. Gandhi, Mahatma, 18691948.2. LawyersIndiaBiography.3. Gandhi, Mahatma, 18691948TravelSouth Africa.4. South AfricaPolitics and government18361909.I. Title.

DS481.G3D4732013

340.092dc23

[B]2013021967

Manufactured in the United States of America

22 21 20 19 18 17 16 15 14 13

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

In keeping with a commitment to support environmentally responsible and sustainable printing practices, UC Press has printed this book on Natures Natural, a fiber that contains 30% post-consumer waste and meets the minimum requirements of ANSI/NISO z39.48-1992 ( R 1997) ( Permanence of Paper ).

To Kathleen

CONTENTS

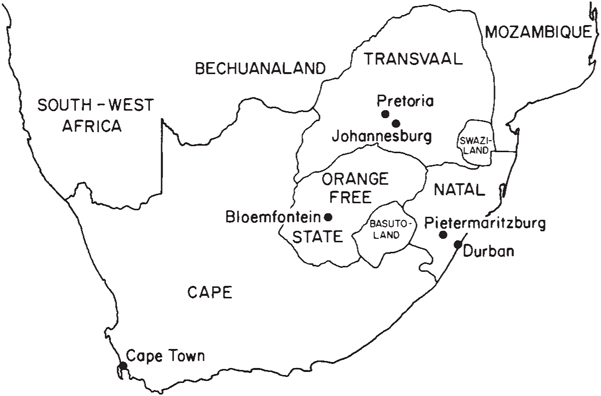

South Africa in Gandhis time. Courtesy of Cornell University Press.

INTRODUCTION

To other countries I may go as a tourist, but to India I come as a pilgrim.

MARTIN LUTHER KING, JR. , on the occasion of his visit to India, 1959

THE IMAGE THE WORLD HAS of Mohandas Gandhi is a stark one. Say the name Gandhi, and the listener invariably conjures up a vision of an elderly, unassuming, bald-headed man. He peers at us through well-worn wire-rimmed glasses, notable because they constitute one of the few items owned by one who has stripped himself of virtually all material possessions. As we see him, he wears not manufactured clothing from Englands factories, but plain, white, homespun cotton from Indias fieldsand a minimum of that, too. He is an ascetic man: he prays, he keeps silence, he fasts, he refrains from wine, meat, and sexual relations. He knows the strength he has in the political arena is derived from decidedly higher sources: his clear and unswerving devotion to the cause of Indian freedom and a view of life that sees the spiritual as the underpinning of the political.

There is, however, another Gandhi. We find a photograph of him in the Sabarmati Ashram in Ahmedabad, India. The place is Johannesburg, the year about 1905. In this picture a tie, a starched shirt, and a three-piece suit replace the homespun. A younger Gandhi, with a head of hair and a striking mustache, sits with authority in an office chair placed outdoors for the occasion of this photograph. Surrounding him are four members of his staff, including, on his immediate left, the smiling Sonja Schlesin, his longtime secretary, and, on his immediate right, H. S. L. Polak, his trusted associate. Dominating the picture, and found slightly above Gandhis head, is a large opaque window in the center of a brick wall with these words carefully arranged on it: M. K. Gandhi. Attorney.

Despite his having studied and practiced law for twenty-three years (18881911), this is the Gandhi about whom the world knows little.

My own image of Gandhi had always been that of the asceticuntil 1978, when I encountered a small volume entitled The Law and Lawyers . Gandhi was named as the author, but I quickly noted it was not a monograph by Gandhi but rather a collection of statements he made over the course of his life about the law and lawyers, ably compiled and edited by S. B. Kher. In it I learned for the first time that Gandhi himself had practiced lawfor a short time in India, but chiefly in South Africa, where he worked and resided for the better part of two decades.

Curious, I headed for the library to locate a biography of his life as a lawyer. There was none. Because the library was a superb one (that of the University of Chicago Law School), I felt relatively secure in concluding that none had been written. I resorted to the standard biographies. Relying almost entirely on what little Gandhi himself had written about his time in the law, they did little more than acknowledge in passing his having studied and practiced law. No one, it seemed, had made an investigation of his long years in the law. No one had asked whether his professional experiences influenced the development of his philosophy and practice of civil disobedience. No one had explored how his legal career shaped the man. It was as if the two decades Gandhi had spent in the law had been declared irrelevant by all his many biographers. This was as stunning as it was inexplicable. Civil disobedience is the conscientious breaking of the law. Gandhi was a civil disobedientand became one while he was a practicing member of the legal profession . Was there no relationship between Gandhis practice of law and his embrace of civil disobedience? Was there no relationship between Gandhis practice of law and the person he became over those years?

I set about writing this biography of Gandhis life as a lawyer to answer those questions and to explain how Gandhis experience as a lawyer set him on a path that would lead to his being one of the preeminent figures of the twentieth centurywith a dramatic impact on the twenty-first.

GANDHIS EXPERIENCES IN THE LAW

Had Gandhi become the physician he wanted to become rather than the lawyer his family insisted he become, it is quite likely that the Indian independence movement would have taken an entirely different trajectory, revolutions around the globe would have more often been violent rather than nonviolent, and Mohandas K. Gandhi would not have developed into Indias leading twentieth-century nationalist. But the man before the Mahatma did become a lawyerand that made all the difference.

That and the South African legal system. Sent abroad as a novice lawyer, it was Gandhis intention simply to earn some money for himself and his family. Before long, however, he found himself at the center of the fight for Indian civil rights in British South Africa. Because he had been trained for the bar in London, Gandhi had come to take British fair play as a settled expectation that he then projected onto the courts of Britains South African colonies. So it was quite natural for the young lawyer to look to the legal system for help in defending against attacks on Indian rights. Gandhis belief in the capacity of the courts to render justice was so strong that in South Africa he repeatedly knocked on the legal systems door for justice for his community. The door rarely opened. He kept knocking. The more he knocked, the less frequently it opened. This repeated, persistent, and finally predictable refusal of the legal system to render justice to South Africas Indians slowly but inexorably frustrated Gandhi. It drove the lawyer out of the legal systemas most of us understand itand into the arms of civil disobedience.

Next page

![Gandhi - Gandhi: [the true man behind modern India]](/uploads/posts/book/175484/thumbs/gandhi-gandhi-the-true-man-behind-modern-india.jpg)