GANDHI

Jad Adams

For Julie

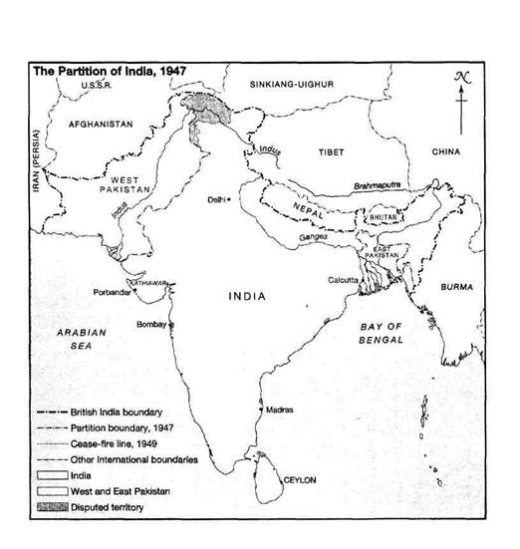

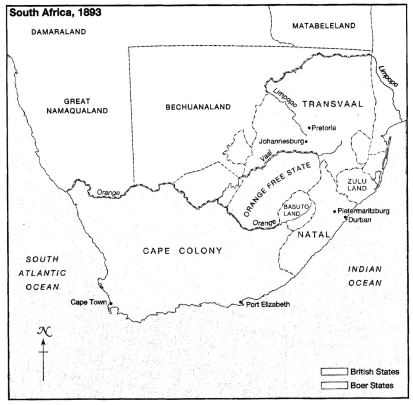

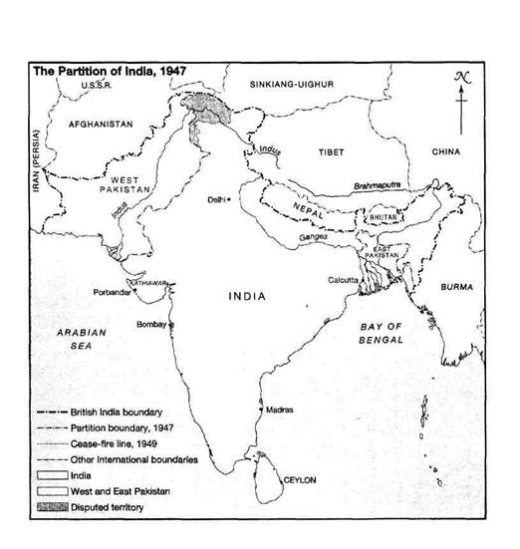

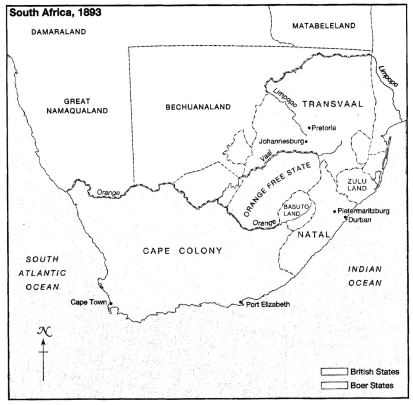

Maps

Introduction

Naked Ambition

My life is its own message.

THE WORLD-CHANGING EVENT of 1930 was recorded in every national newspaper and newsreel: in an act of defiance Gandhi had challenged the British Empire by taking untaxed, contraband salt from his own land. Accounts report how he then cleansed himself in the sea, pictures of the time showing the tiny white-clad individual against the pure-white salt flats, a symbol of purity challenging the greatest empire the world had known. As he held up the white crystals for all to see, the nationalist poet Sarojini Naidu cried out, to the acclamation of the crowds: Hail, deliverer!

The iconic image is, as usual in these cases, a fake, a concoction of journalists, film-makers and adulatory biographers. Gandhi did go to Dandi, but the images and accounts of it are a carefully thought out, stage-managed set-piece. The famous picture shows Gandhi three days after he arrived, picking up salt at nearby Bhimrad, ten kilometres from the coast and twenty-five from Dandi. Sarojini Naidu was present when he reached Dandi but she did not utter the often reported cry (which would have been a disappointingly trite utterance, for her). The great photographic moment was a re-enactment for the cameras of the event that had taken place on a muddy beach where the salt was not visible and the act therefore less apparently symbolic.

Gandhis achievement was not in defying the law to gather salt (peasants did that with impunity all the time): it was in announcing that he was going to break the law, then marching for twenty-four days to do it, giving the media plenty of time to comment and orchestrate their coverage.

His political colleagues had been bemused, never considering salt in the slightest bit important; likewise the British authorities, who made no show of strength because of the pettiness of the act. But Gandhi knew the importance of symbolism. He was the most spiritual of men, praying twice daily and incessantly murmuring the name of God, and his attention to diet extended to counting the number of raisins he ate. But more significant than any of his spiritual knowledge was his awareness of image. His oddly assorted clothing reflected the way he had striven to make himself the message: the top-hat and spats of a London barrister, the plain shirt and dhoti of an indentured labourer, the homespun clothes of those who rejected British cloth imports. Finally, when he had an army of supporters clad in homespun yarn, he appeared wearing almost nothing, nude but for a loincloth. This was the image that went around the worldone near-naked holy man against an empire. He became an icon. At that time only Charlie Chaplin and Adolf Hitler had achieved such worldwide recognition for their image, such that everyone knew exactly what they stood for.

Gandhis life is the ultimate challenge for a biographer: it was so multi-faceted, and there is so much surviving contemporary information about it. Many people demonstrate two aspects of interest in their lives. A national leader may have an incandescent political career and a lurid sex life, but nothing else worthy of comment. It is not unusual to encounter social reformers who have a complex relationship with food, or with religion; many people famous for their achievements have a tumultuous family life. Gandhis political life, spiritual life, family life and sex life were all fascinating; his relationship to food could fill a volume in itself.

In all these areas, Gandhis own testimony survives, his collected works run to one hundred volumes: books, articles, letters and speeches. For some world figures such as Homer there is no reliable biographical information, for some such as Abraham there is little, for Gandhi there is a superabundance. Gandhi knew what use would be made of this material, and he was not encouraging: My writings should be cremated with my body. What I have done will endure, not what I have said or written.

Notwithstanding his warning, this biography is based on primary sources, on his own writing and that of people who were close to him. Chief of these were his secretary between 1917 and 1942, Mahadev Desai, who wrote a nine-volume diary, and Desais assistant and later the principal secretary, Pyarelal, who was with Gandhi from 1920 until his death. With his sister Sushila Nayar, Gandhis doctor, Pyarelal wrote a ten-volume biography. Of all the other material used here the work of eyewitnesses, particularly in diaries or near-contemporary accounts, is taken as paramount, in preference to later interpretations.

Gandhis own two autobiographies, one on his life to the 1920s and the other on his South African experiences, are a guide not so much to the events (though sometimes they are the only record) but to the relative importance he placed on the various aspects of his life. Thus much less emphasis needs to be given to the law and politics when Gandhi was a student in London than to his vegetarian diet, because that was what obsessed him. In South Africa the life of the ideal communities he set up and his own celibacy were to him the most important part of his work. The battle with the government over Indian rights was what he did, the struggle with his sex drive was what he was. Like many very ambitious men, Gandhi was highly sexed: the interest for the biographer is how he tried to contain this sexuality, and how rivetingly candid he could be about it in his own writing.

Any reliance on Gandhis own writing immediately opens up question of trust: did he tell the truth? His autobiography is subtitled The Story of My Experiments with Truth, but what kind of truth was it that he believed in? Any politician could say they experimented with the truth, which would be a euphemism for lying.

There is some evidence that the incompetence Gandhi showed in his early public life has been exaggerated, giving a more dramatic impression of his later resounding successes. Later historians have found his contribution to South African politics greatly overstated. His followers were certainly left disappointed after his supposed agreements with the South African government unravelled. It is not over such matters or their interpretation that the real question of Gandhis veracity emerges, however. In terms of mere fact, Gandhis truth is a selective one not so much for what he wants to conceal as for what he wants to explore in his past: his moral development. The Autobiography started as a series of instructive articles in his newspaper Young India, where each separate chapter had to stand alone with its own moral. The work is therefore fashioned as a series of lessons, as the trials of Gandhi or Gandhis progress after one of his favourite books, Bunyans spiritual biography The Pilgrims Progress. Gandhi is less concerned with the factual accuracy of an incident than with its spiritual meaning.

For Gandhi the striving for truth was not an attempt to reach unquestioned factual accuracy, but a stretching out towards spiritual perfection. For him, truth was eternal and, conversely, if something were transient it could not be true. Often in my progress I have found faint glimpses of the Absolute Truth, God, and the daily conviction is growing on me that He alone is real and all else is unreal, he wrote.

Next page

![Gandhi Gandhi: [the true man behind modern India]](/uploads/posts/book/175484/thumbs/gandhi-gandhi-the-true-man-behind-modern-india.jpg)