Discover great authors, exclusive offers, and more at hc.com

Available wherever books are sold.

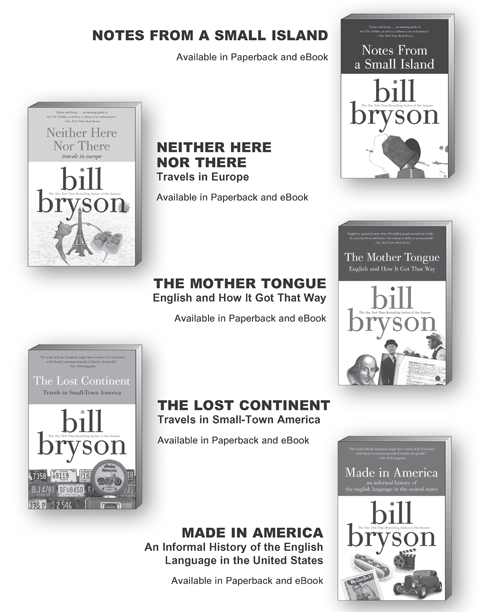

The Lost Continent

Notes from a Small Island

Mother Tongue

Neither Here nor There

Made in America

A Walk in the Woods

Im a Stranger Here Myself

In a Sunburned Country

Brysons Dictionary of Troublesome Words

Bill Brysons African Diary

A Short History of Nearly Everything

A Short History of Nearly Everything: Special Illustrated Edition

The Life and Times of the Thunderbolt Kid

Shakespeare: The World as Stage

Brysons Dictionary for Writers and Editors

At Home: A Short History of Private Life

One Summer: America, 1927

Bill Bryson s bestselling books include One Summer , A Short History of Nearly Everything , At Home , A Walk in the Woods , Neither Here nor There , Made in America , and The Lost Continent . He lives in England with his wife.

Discover great authors, exclusive offers, and more at hc.com .

Australia

HarperCollins Publishers (Australia) Pty. Ltd.

Level 13, 201 Elizabeth Street

Sydney, NSW 2000, Australia

www.harpercollins.com.au

Canada

HarperCollins Canada

2 Bloor Street East - 20th Floor

Toronto, ON M4W 1A8, Canada

www.harpercollins.ca

New Zealand

HarperCollins Publishers New Zealand

Unit D1, 63 Apollo Drive

Rosedale 0632

Auckland, New Zealand

www.harpercollins.co.nz

United Kingdom

HarperCollins Publishers Ltd.

77-85 Fulham Palace Road

London, W6 8JB, UK

www.harpercollins.co.uk

United States

HarperCollins Publishers Inc.

195 Broadway

New York, NY 10007

www.harpercollins.com

I n winter, Hammerfest is a thirty-hour ride by bus from Oslo, though why anyone would want to go there in winter is a question worth considering. It is on the edge of the world, the northernmost town in Europe, as far from London as London is from Tunis, a place of dark and brutal winters, where the sun sinks into the Arctic Ocean in November and does not rise again for ten weeks.

I wanted to see the Northern Lights. Also, I had long harbored a half-formed urge to experience what life was like in such a remote and forbidding place. Sitting at home in England with a glass of whiskey and a book of maps, this had seemed a capital idea. But now as I picked my way through the gray late December slush of Oslo, I was beginning to have my doubts.

Things had not started well. I had overslept at the hotel, missing breakfast, and had to leap into my clothes. I couldnt find a cab and had to drag my ludicrously overweight bag eight blocks through slush to the central bus station. I had had huge difficulty persuading the staff at the Kreditkassen Bank on Karl Johansgate to cash sufficient travelers checks to pay the extortionate 1,200-kroner bus farethey simply could not be made to grasp that the William McGuire Bryson on my passport and the Bill Bryson on my travelers checks were both meand now here I was arriving at the station two minutes before departure, breathless and steaming from the endless uphill exertion that is my life, and the girl at the ticket counter was telling me that she had no record of my reservation.

This isnt happening, I said. Im still at home in England enjoying Christmas. Pass me a drop more port, will you, darling? Actually, I said: There must be some mistake. Please look again.

The girl studied the passenger manifest. No, Mr. Bryson, your name is not here.

But I could see it, even upside down. There it is, second from the bottom.

No, the girl decided, that says Bernt Bjrnson. Thats a Norwegian name.

It doesnt say Bernt Bjrnson. It says Bill Bryson. Look at the loop of the y , the two l s. Miss, please.

But she wouldnt have it.

If I miss this bus when does the next one go?

Next week at the same time.

Oh, splendid.

Miss, believe me, it says Bill Bryson.

No, it doesnt.

Miss, look, Ive come from England. Im carrying some medicine that could save a childs life. She didnt buy this. I want to see the manager.

Hes in Stavanger.

Listen, I made a reservation by telephone. If I dont get on this bus I am going to write a letter to your manager that will cast a shadow over your career prospects for the rest of this century. This clearly did not alarm her. Then it occurred to me. If this Bernt Bjrnson doesnt show up, can I have his seat?

Sure.

Why dont I think of these things in the first place and save myself the anguish? Thank you, I said and lugged my bag outside.

The bus was a large double-decker, like an American Greyhound, but only the front half of the upstairs had seats and windows. The rest was solid aluminum covered with a worryingly psychedelic painting of an intergalactic landscape, like the cover of a pulp science fiction novel, with the words Express 2000 emblazoned across the tail of a comet. For one giddy moment I thought the windowless back end might contain a kind of dormitory and that at bedtime we would be escorted back there by a stewardess who would invite us to choose a couchette. I was prepared to pay any amount of money for this option. But I was mistaken. The back end, and all the space below us, was for freight. Express 2000 was really just a long-distance truck with passengers.

We left at exactly noon. I quickly realized that everything about the bus was designed for discomfort. I was sitting beside the heater, so that while chill drafts teased by upper extremities, my left leg grew so hot that I could hear the hairs on it crackle. The seats were designed by a dwarf seeking revenge on full-sized people; there was no other explanation. The young man in front of me had put his seat so far back that his head was all but in my lap. He had the sort of face that makes you realize God does have a sense of humor and he was reading a comic book called Tommy og Tigern. My own seat was raked at a peculiar angle that induced immediate and lasting neckache. It had a lever on its side, which I supposed might bring it back to a more comfortable position, but I knew from long experience that if I touched it even tentatively the seat would fly back and crush both the kneecaps of the sweet little old lady sitting behind me, so I left it alone. The woman beside me, who was obviously a veteran of these polar campaigns, unloaded quantities of magazines, tissues, throat lozenges, ointments, unguents, and fruit pastilles into the seat pocket in front of her, then settled beneath a blanket and slept more or less continuously through the whole trip.

We bounced through a snowy half-light, out through the sprawling suburbs of Oslo and into the countryside. The scattered villages and farmhouses looked trim and prosperous in the endless dusk. Every house had Christmas lights burning cheerily in the windows. I quickly settled into that not unpleasant state of mindlessness that tends to overcome me on long journeys, my head lolling on my shoulders in the manner of someone who has lost all control of his neck muscles and doesnt really mind.

My trip had begun. I was about to see Europe again.

The first time I came to Europe was in 1972, skinny, shy, alone. In those days the only cheap flights were from New York to Luxembourg, with a refueling stop en route at Keflavk Airport at Reykjavk. The airplanes were engagingly past their primeoxygen masks would sometimes drop unbidden from their overhead storage compartments and dangle there until a stewardess with a hammer and a mouthful of nails came along to put things right, and the door of the lavatory tended to swing open if you didnt hold it shut with a foot, which brought a certain dimension of challenge to anything else you planned to do in thereand they were achingly slow. It took a week and a half to reach Keflavk, a small gray airport in the middle of a flat gray nowhere, and another week and a half to bounce on through the skies to Luxembourg.