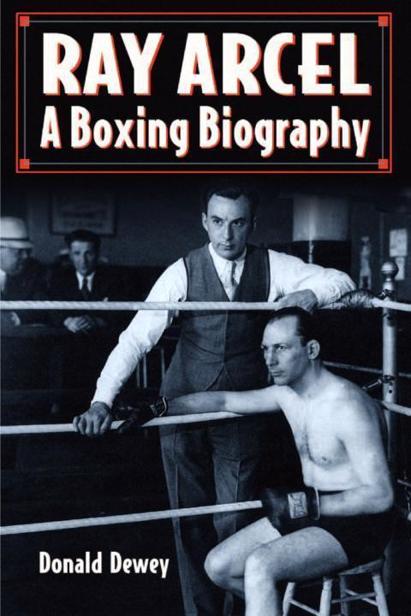

A Boxing Biography

Donald Dewey

ix

Chapter 197

In addition to Stephanie Arcel, the author is indebted to numerous people for the time they gave him to answer often irritating questions and to point him in the right direction to annoy other people. I would particularly mention in this regard Ray Arcel's granddaughters, niece, and several in-laws; Jerry Izenberg; the late Bill Gallo and Gil Clancy; Fran Kessler; David Smith of the New York Public Library; Steve Siegel; and Roy Singh.

If Ray Arcel had been in politics, he would have been a key advisor to every president from Woodrow Wilson to Bill Clinton. If he had been in the motion picture industry, he would have been responsible for putting both Rudolph Valentino and Denzel Washington on their feet in front of the camera. As an exercise guru, he was active before Jack LaLanne was born. He was associated with more championships than the New York Yankees, more crash diets than Jenny Craig, and more conmen than P.T. Barnum. One of his most conspicuous rewards for his Zelig-like ubiquity was a Mob-ordered murder attempt that left him barely clinging to life.

Arcel's realm was the theater of physical prowess and organizational savagery known as professional boxing. Without his prominence for much of the 20th century, backers of the sport would have had considerably less to back, opponents of the sport would have had markedly less to rail against, and the very notion of professional boxing as a sport would have lost much of the credibility it has sweated to retain. His prominence was all the more startling insofar as he himself was not a fighter, a promoter, or a manager, but a trainer-a role the popular imagination has usually configured as a sweater, a peak-cap, and a towel that jump up into the ring with a stool whenever the bell announces the end of a boxing round. Arcel didn't disdain such stereotypes; he just made sure they remained irrelevant.

Arcel's journey through prizefighting crossed all the ethnic timelines and tested all the structural power lines. When he started out, professional boxing was an Irish and Jewish escape hatch from slums; before he was finished, he had guided Italians, African Americans, and Latinos toward ghetto exits. The promoters who benefited from his skills ran the gamut from neighborhood gym satraps to shadowy underworld bosses to the glitzy overworld dream guys of casino hotel arenas. Long before HBO and ESPN were putting their call letters into the ring, he was going through boxing's ABCs as the front man for a national television network. He shook hands with mayors and governors, defied congressmen, and received the rarest of honors from presidents. Ray Arcel was always a main event.

He was also an anomaly in a game that was never play. His austere persona and laconic pronouncements constantly drew comparisons with Talmudic scholars and others who were attributed with more intellectual than physical priorities. He was fluent at turning questions back on the questioner, whether those doing the asking were government bodies or newspapermen. The former fumed and threatened retaliation, the latter welcomed him to their club of visceral skepticism. It was the least of the paradoxes of Arcel's career that someone so unassuming when he wasn't directly involved in training should have been able to reduce the most critical sportswriters of his age (Damon Runyon, Red Smith, Bill Heinz, etc.) to a fan club. "Don't be a district attorney" was a phrase attached to him for decades - both as a warning that he had said as much as he intended saying on a given topic and as a lament that there were too many accusations to go around to be smug about landing on some specific one. Inevitably, this produced some boilerplate tales about him that contained everything except fact and some defenses of his own that contained everything except candor.

Statistically, Arcel's record of training champions, from Benny Leonard to Roberto Duran and Larry Holmes, set precedents; in absolutely every one of the classic boxing weight categories at least one charge ended up wearing a jeweled belt. But from the very start, Arcel's career raised questions, not least why a teenager said to be intellectually gifted enough to be accepted by New York's prestigious Stuyvesant High School and encouraged at home to become a doctor would end up as a boxing trainer. The choice was not some lazy development of circumstance, either; before he was out of his teens, when others his age were contemplating romantic lives, including that of being a boxer, he let it be known that training was for him. Within the boxing world there was similar wonder about why, despite regular opportunities, he generally eschewed the more lucrative role of being a manager. To these and similar questions his admirers in and out of the media were usually content replying with some variation on "he worries about fighters, not the fights." Arcel's own response? "Don't be a district attorney."

For someone so heavily identified with New York, Boston, London, and other metropolitan boxing centers throughout his long life (he died at the age of 94 in 1994), Arcel, in fact, saw the light of day in Terre Haute, Indiana. It wasn't a turn-of-the-century Terre Haute of straw hats and ice cream parlors, but of the Socialist firebrand and union organizer Eugene V. Debs, an early political acquaintance of Arcel's father. When the family was forced to move to New York City because Arcel's fatally ill mother wanted to be near her parents for the end, the daily reality became that of the scuffling Jewish neighborhoods portrayed by Sergio Leone's Once Upon a Time in America where the brutality of violence was inseparable from the brutality of poverty. It was in this ambience that Arcel discovered what would be the economic, political, and social center of his life - the gymnasium. Over the years that followed, the gyms would have many names and locations (some would have the same name in different locations), but always they would serve as Arcel's canvas, both literally and figuratively.

One of baseball's oldest cliches is that the sign of a good umpire is his consistency. By that criterion Ray Arcel would have made a phenomenal umpire over decades of replies to questions about his ring experiences, his impressions of given fighters and promoters, and his views on the techniques and cultural impact of professional boxing. So consistent was he in his responses that sifting through volumes of newspaper columns and magazine articles about him leaves the suspicion that, much more than in the cases of other sports figures, writers took to lifting quotes from each other, commas and colons included. Recordings of interviews with sports and non-sports questioners alike also replay the exact same anecdotes and reminiscences, the principal additions being the subject's adenoidal New York tones and intermittent dry laugh. What undercuts the suspicion of mass plagiarism, however, is that even an extensive memoir he compiled with his second wife Stephanie at her request resounds with tales, turns of phrase, and a narrative arc identical to those scattered throughout hundreds of periodicals from Boston and New York to Los Angeles and Seattle. What Ray Arcel said once, he said a thousand times, and mostly without contradicting himself.