Contents

For Samuel, Eliza, and Hadleigh

Preface

The roots of this book go back to my childhood. Although I was raised in Berkeley, my father grew up in Grass Valley, the heart of the California gold country. The youngest of four sons, he was the first male in the family to get out of the mines. Before he left home, however, my grandfather had insisted that he learn the family trade. So Dad knew a lot about quartz mining, including how to blow up a rock wall so that all the pieces fell neatly into one pile. I always hoped to see a demonstration, but never did. Instead, I had to settle for a diagram of a standard twenty-two-hole blasting pattern. Four or five times a year, we journeyed back to Dads old hometown, to Grandmas house, and there I was literally surrounded by hard-rock miners. From these experiences, I picked up bits and pieces about gold rush California. I also learned that hard-rock mining was a skill that had to be honed to near perfection and not something that could be mastered in a weekend.

These childhood experiences, however, didnt trigger the writing of this book. That decision came much later and more or less through a back door. In the 1980s, while doing research for a book on John Quincy Adamss congressional career, I dipped into pamphlets, letters, and reminiscences written by his slaveholding adversaries. As expected, I learned that most of them regarded the former president as an able but nasty old man. To my surprise, however, I also discovered that shortly after his death in 1848, many of them fantasized about taking their slaves to California and getting rich mining gold. None of them, as far as I could tell, knew the first thing about mining, much less hard-rock mining. They all seemed to think it was easy, something any slave could do. And nearly all of them deemed the slaveholding Souths loss of California a major turning point in North-South relations. Had they gained control of the gold fields, they contended, their lives and the lives of their fellow slaveholders would have been golden.

A few years later, while studying free-state politicians who sided with the South in North-South struggles, I discovered that some of the more noteworthy came from my home state. Somehow I had missed learning that fact. Somehow I had gone through the California schools from kindergarten through graduate school and never realized that many of the states early leaders had been Northern men with Southern principles, that several might as well have been representing Mississippi or Alabama in national affairs, and that the states entire congressional delegation on the eve of the Civil War had supported John C. Breckinridge, the pro-slavery candidate for president. Either such details had been omitted from the curriculum, or I simply had not been paying attention. In any event, one reason for writing this book has been to bring myself up to speedto learn material that I should have learned forty or fifty years ago.

In the process, Ive had plenty of help. The Bancroft and Huntington libraries were central. They are literally gold mines for California scholars, and the staff at both institutions alerted me to documents that I would probably never have found on my own. Also helpful were archivists at the state library, the California Historical Society, the Nevada County Historical Society, the Placer County Historical Society, the Empire Mine, and other depositories I visited over the years. As in the past, the librarians at my home institution, the University of Massachusetts, have been diligent in getting me the microfilm and obscure books that I needed. And, as in the past, I have relied heavily on my colleagues in the history department for advice and direction, especially Bruce Laurie and Barry Levy, who on more occasions than I can count listened patiently to my ramblings. I have also taught four writing seminars on the gold rush and the coming of the Civil War, and some of the students in those classes have been computer whizzes, finding facts and figures on the Internet that I never knew existed. Finally, I owe a big thanks to Jennifer Bonin for creating the maps and to Jane Garrett, Emily Molanphy, Leslie Levine, and the staff at Alfred A. Knopf for shepherding the manuscript through publication.

Prologue

TODAY THE LAKE IS SURROUNDED BY GOLF COURSESONE PUBLIC, three privateall scrambling to get their share of its water. To conservationists the courses are a nuisance, a curse on the environment and a danger to the waterfowl, but the fairways and clubhouses have been San Francisco landmarks since the 1920s and have too many patrons to be uprooted. One of the private clubsthe famous Olympic Clubhas hosted four U.S. Opens. Ben Hogan played and lost there to an unknown golfer named Jack Fleck. Thousands of lesser golfers, meanwhile, have taken their clubs to the nearby public course at Harding Park.

Of the men and women who trudge the fairways of these four courses, eat and drink in the clubhouses, tell stories and lie about their handicaps, many are well aware of the Hogan-Fleck match. A few even saw it happen. Only a handful, however, are aware that just to the east of the southern tip of the lake is the place where a U.S. senator was shot to death, the last U.S. senator to be killed in California before Bobby Kennedy. Scarcely one in a thousand knows that story.

One cant blame them. It happened long ago, sixty years before any of the courses were built, before the Civil War, actually, September 13, 1859, to be precise.

At that time Lake Merced was a very popular dueling ground. Dueling was illegal in San Francisco, but the area just behind the barn at Lake House Ranch was remote enough that a duel could still be carried out in relative privacy and isolation from the law. Also, there were certain to be some technical difficulties determining jurisdiction, had the authorities tried to interfere. For the lake is not in San Francisco proper, but south of the city, on the border between San Francisco and San Mateo counties.

The duel was between David S. Terry, the chief judge of the state supreme court, and Senator David Broderick.1 They were both Democrats, but from hostile ends of their party. Broderick, the senator, opposed the expansion of slavery, and Terry, the judge, was part of what was then called the Chivalry wing of the California Democratic Party. The Chivs were pro-South and pro-slavery. They were also determined to eliminate Broderick and other California free-soilers from positions of power. At the time of the duel the Chivs had the upper hand and seemed to be just on the edge of victory.

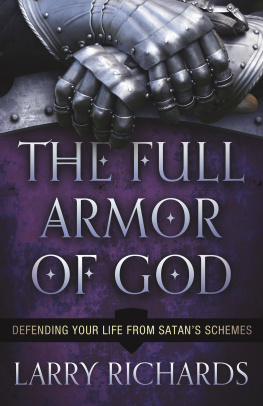

The judge pushed matters to a head. He probably couldnt help it. Even his friends described him as truculent. He was young for a judge, just thirty-six, but had been on the state supreme court for four years, chief judge for two years. He was a big man, six feet three and over 220 pounds, with a noticeably flat face and a large bulbous nose. He was clean shaven except for chin whiskers. He wore his hair long, in the Southern style.

David S. Terry, chief justice of the California Supreme Court. Reprinted from Jeremiah Lynch,

Next page