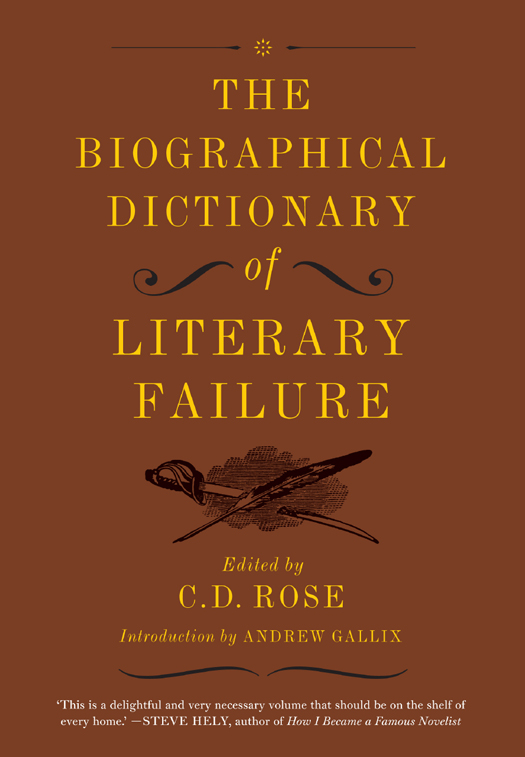

The Biographical Dictionary of Literary Failure

COPYRIGHT 2014 BY CHRISTOPHER ROSE

INTRODUCTION COPYRIGHT 2014 BY ANDREW GALLIX

First Melville House printing

NOVEMBER 2014

MELVILLE HOUSE PUBLISHING

145 PLYMOUTH STREET

BROOKLYN, NY 11201

and

8 BLACKSTOCK MEWS

ISLINGTON

LONDON N 4 2 BT

mhpbooks.com

facebook.com/mhpbooks

@melvillehouse

ISBN : 978-1-61219-378-6

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS

CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA :

Rose, C. D., author.

The biographical dictionary of literary failure / C. D. Rose ; introduction by Andrew Gallix.

pages cm

ISBN 978-1-61219-378-6 (hardback)

ISBN 978-1-61219-379-3 (ebook)

1. AuthorsBiographyDictionariesFiction. 2. Failure (Psychology)Fiction. I. Title.

PS3618.O78284B56 2014

813.6dc23

2014002517

DESIGNED BY SAM POTTS

v3.1

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

ONCE upon a time this book was a website celebrating the lives of writers who have achieved some measure of literary failure. Every week a new biography was posted, anonymously, and after a year all the entries were duly deleted, thus enacting their own subject matter. It struck me as a beautiful echo of Maurice Blanchots oft-quoted prophecy that literature is heading toward itself, toward its essence, which is its disappearance. I also realised that this online compendium, culled from the slush pile of history by C. D. Rose and his team of researchers, was simply too valuable to be allowed to disappear without trace, however romantic the gesture.

The impulse to tell the tales of those whose tales will remain untold is akin to that which inspired the creation of the various libraries of unpublished and unwritten books (often modelled on the library in Richard Brautigans The Abortion). Hannah Arendt once wondered if the very notion of unappreciated geniusthe pote maudit whose prodigious talent goes unrecognised in his or her lifetimewas not simply the daydream of those who are not geniuses. I suspect that there is indeed a touch of Schadenfreude about the pleasure derived from reading these anecdotes of writerly woe. The cumulative effect produces a kind of comique de rptition that takes its cue from Beckett: Ever tried. Ever failed. No matter. Try again. Fail again. Fail better. There is a slight sadistic thrill each time you move on to the next sob story, and try to guess how this hapless scribe will manage to fail even better than the previous one. I also suspect that the editorwho had achieved some measure of literary success, but not, alas, the breakthrough he deservedmay have been exorcising some demons of his own.

Literary biography is a by-product of literature: the writers life is read, rebours, in the light of her works. Had she not written them, we would probably show no interest in the minutiae of her existence. Literature redeems daily life, endowing it with meaning; recasting it, teleologically, as a prolegomenon to the work. By its very nature, The Biographical Dictionary of Literary Failure raises some crucial questions. Literature is all about readers losing themselves in books and writers losing themselves in a language that speaks itself. If, as Roland Barthes argued, the death of the author marks the birth of literature, does the death of literatureits loss, or failure to come into beingmark the rebirth of the author? Is it possible, as Jean-Yves Jouannais believes, to be a writer without writings? The writer doesnt really want to write, he wants to be; and in order to truly be, he must face up to the difficult challenge of not writing at all, states one of Luis Chitarronis characters in The No Variations. Not writing, for a writer, may be writing by another means, or rather the logical conclusion of the literary enterprise, for, as Enrique Vila-Matas highlights, in the end, every book pursues non-literature as the essence of what it wants and passionately desires to discover.

The fifty-two writers manqus whose names are saved from oblivion in this dictionary certainly did not fail through lack of ambition. Quite the contrary. Most of them devoted their lives to the pursuit of some Gesamtkunstwerk that was supposed to encompass the whole of being, but resulted in nothingness. This quixotic quest for a volume in which everything would be said extends from epic poetry to Joyces Ulysses through the Bible, the Summa Theologica, Coleridges omnium-gatherum, the great encyclopedias, Prousts masterpiece, Mallarms (non-)conception of Le Livre, and Borgess total bookthe catalog of catalogsrumoured to be lurking on some dusty shelf in the Library of Babel. Take the example of Edward Nash, who was convinced that absolutely everything that needed to be written could be expressed, if only he managed to find the perfect way of describing an individual cloud or wave. He spent most of his days staring at the sea and sky, and most of his nights filling notebooks with odd words and phrases. Never once was he able to complete a single sentence, unlike Chad Sheehan, who, in a flash of inspiration, jotted down the perfect opening to a story. Whenever he attempted to compose the following sentence, however, he ended up with the opening line to another story. This oscillation between totality and fragmentationalready experienced by the Jena romantics, often regarded as the originators of modern literatureis best illustrated by Nate Warronker, who painstakingly planned to write the longest novel in history without ever considering its actual content. Felix Dodge embodies another crucial aspect of literary modernity: the failure to even begin the work, let alone complete it. He spent twenty years limbering up for a magnum opus that would have included everything that was or could be known to humanityhad he not died just as he was about to put pen to paper.

In 1975, Ulises Carrin declared: The most beautiful and perfect book in the world is a book with only blank pages. Such books of absolute whiteness had featured in Eastern legends for centuriesechoed by the blank map in The Hunting of the Snark or the blank scroll in Kung Fu Pandabut they only really appeared on bookshelves in the twentieth century. They come in the wake of Bartleby (Melvilles scrivener who stops scrivening), Rimbauds renunciation of poetry and Hofmannsthals aphasia-afflicted Lord Chandos. They are contemporaneous with the Dada suicides, Wittgensteins coda to the Tractatus, the white paintings of Malevich or Rauschenberg, Yves Kleins vacant exhibitions, as well (of course) as John Cages mute music piece. Blankness is the sine qua non for inclusion in the BDLF, but it is seldom sought after directly. Manuscripts and books remain blank to us through being censored, lost, drowned, shredded, pulped, burned, used as cigarette paper or wrapped around kebabs, fed to pigs or even ingested by their own authors Marta Kupka produces a blank memoir, not of her own volition, but due to a potent combination of failing eyesight and dried-up typewriter ribbon. The closest we get to a genuine hankering after blankness comes from the two erasers included in the book: Virgil Haack, who whittles down his work to a single word ( la Franois Le Lionnais), and Wendy Wenning, who edits her thousand-page epic until she is left with a perfectly blank sheet of paper. It is suggested that it may be the fear of someone actually reading their work that causes authors like Stanhope Barnes, or T. E. Lawrence before him, to lose their manuscripts at Reading station. I think this comment applies to all the entries. These brief biographies are sketches that merely gesture towards the possibility of narrative development; stories that are cut short or fall silent. Stories that