The First of Men

The First of Men

A LIFE OF GEORGE WASHINGTON

JOHN E. FERLING

Oxford University Press, Inc., publishes works that further Oxford Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education.

Oxford New York

Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi

Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi

New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto

With offices in

Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece

Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore

South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam

Copyright 1988 by The University of Tennessee Press / Knoxville

Published by Oxford University Press, Inc.

198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016

www.oup.com

First published in hardcover in 1988 by The University of Tennessee Press

First issued as an Oxford University Press paperback, 2010

Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced,

stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means,

electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise,

without the prior permission of Oxford University Press.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Ferling, John E.

The first of men: a life of George Washington / John E. Ferling.

p. cm.

Originally published: Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, c1988.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-19-539867-0 (pbk)

1. Washington, George, 17321799.

2. PresidentsUnited StatesBiography.

3. GeneralsUnited StatesBiography.

4. United States. Continental ArmyBiography. I. Title.

E312.F47 2010 973.41092dc22 [B] 009033423

9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Printed in the United States of America

on acid-free paper

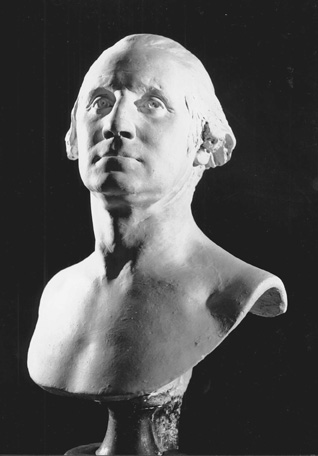

Frontispiece: Clay bust of Washington, by Jean Antoine Houdon (1785).

Courtesy of the Mount Vernon Ladies Association of the Union.

The American Revolution... is fixed forever.

Washington began it with energy,

and finished it with moderation.

LOUISE FONTANES, 1800

Time, like an ever-rolling stream,

Soon bears us all away;

We fly forgotten, as a dream

Dies at the opning day.

ISAAC WATTS

Contents

Illustrations

MAPS

Preface

John Adams doubted that an accurate history of the great events of his lifetime could ever be written. The story of those events would be one continued lie from one end to the other, he once predicted in a not uncustomarily bilious moment. The essence of the whole, he went on, will be that Dr. Franklins electrical rod smote the earth and out sprang General Washington. That Franklin electrified him with his rod, and thenceforth those two conducted all the policy, negotiations, legislatures, and war.

George Washington expressed greater confidence in the capabilities of future historians, and he was even sufficiently realistic to imagine the darts which I think [will] be pointed at me by those who would come to write of him and his age. However, he did expect high standards of his biographers. He hoped they would have a disposition to justice, candour and impartiality, and... [a] diligence in investigating the source materials.

Washington might have been surprised by what was written in the years following his death. For a century or more his biographers were unable to cut through the legends that had come to surround the man. If Adamss ideas about the folklore likely to surround Washington and Franklin were exaggerated, the human Washington did indeed seem to be elusive, and he was handed from generation to generation as a stylized, fanciful figure, as lifeless as the image of the man that peers out from the myriad paintings suspended on quiet museum walls. In a sense, it was as though Washington was too monumental to contemplate, save in the most heroic terms. But in another sense it was as if Washington could not bear scrutiny, for fear that he would prove to be all too human.

My introduction to Washington, fortunately, came after historians had begun to penetrate the mists of heroic legend. A work by Marcus Cunliffe, which I read while still an undergraduate, first made me aware that Washington was, after all, arrestingly human, even though the author confessed his inability fully to distinguish the man from the myth. Later, in graduate school, I read Bernhard Knollenberg on Washingtons early years, as well as some of the voluminous works of Douglas Southall Freeman and James Thomas Flexner, each of whom had played an important role in the mortalization of Washington.

Still, something seemed to be lacking. Too often the engines that drove the private man seemed out of sync with the forces that pushed the public figure. Illogically, there seemed to be two Washingtons, and the inclinations of the one appeared never to intrude upon the actions of the other. This added another intriguing element to the endless fascination of this man, but it was not until my research led me rather circuitously into a study of early American military history that I first began to try to come to grips with Washington. From that beginning I was led to this study, drawn in the hope that I might fathom what I perceived to be an incompleteness to the figure of the historical Washington.

From the outset it was my intent to write a one-volume biography. My goal was to produce something less grand than a man-and-the-times study, yet to probe Washingtons era in sufficient depth that I might draw on the explosion of studies set off by the recent celebration of the American Revolution Bicentennial.

Not every reader will agree with my assessment of Washington, particularly with those sections that are less than flattering in their judgment. In fact, in the course of the years required to complete this study, some of my own assumptions about Washington were changed, and I came to a greater admiration of many facets of the man, particularly of his courage, his realization of his limitations, his ability to make difficult decisions, his diligent striving for self-improvement, his willingness to work, the gentle love and abiding steadfastness which he exhibited toward his family, and, with one or two glaring exceptions over a long lifetime, the sense of loyalty and constancy he manifested toward those who remained faithful to him. Of course, there were dartsthe harsh appraisal that Washington anticipatedbut I am confident that these arrows were unsheathed only after I had adhered to the guidelines for fairness that Washington had asked of biographers.

This study could not have been completed without the assistance of many others. Considerable financial support was provided by the Learning Resources Committee of West Georgia College. Albert S. Hanser and Ted Fitz-Simons generously cooperated by providing teaching schedules that facilitated the completion of the study, while the Arts and Sciences Executive Committee and Dean Richard Dangle of West Georgia College assisted by granting my request for a reduced teaching schedule.

I am indebted to numerous people who provided kind assistance in the course of my research. Long days and nights away from home were made more pleasant by the courteous and friendly aid I received from librarians and historians in many libraries. I am grateful for the guidance and encouragement offered by W.W. Abbot, Dorothy Twohig, Philander Chase, and Beverly Runge of the George Washington Papers at the Alderman Library of the University of Virginia. The cordiality with which I was welcomed at the Mount Vernon Library made the hours I spent in that bucolic setting all the more pleasurable. The same can be said of my work at the National Archives, Library of Congress, Massachusetts Historical Society, Connecticut State Library in Hartford, the New York Historical Society, and the New York Public Library.

Next page