2016

TO PHILIP EISNER

A great friend and writer,

fellow traveler through the darkness

and the light

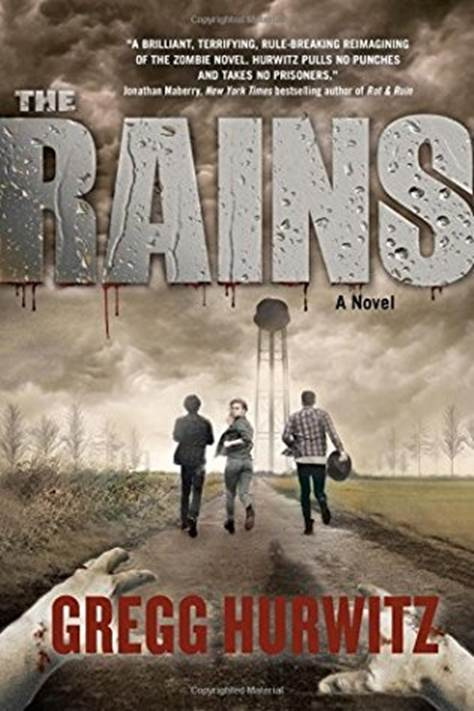

The document you are reading does not-cannot-exist. If youre reading this, your life is at risk. Or I should say, your life is at even greater risk than it was already. Im sorry to burden you with this. I dont wish you the kind of harm that came to me and the others from Creeks Cause. This is what Ive managed to piece together since it all began. I wrote it down knowing that words are more powerful than bullets-and certainly more dangerous. All is probably lost already.

But maybe, just maybe, these pages will give you a chance.

I hope youre up to it.

The day after the day after tomorrow, in a state nestled among others

It was past midnight. I was still working in the barn when I heard the rolling door lurch open. I started and lost my grip on a block of hay. It tumbled off the baling hooks.

It was creepy out here with the wind whipping across the roof, fluttering loose shingles. Bits of hay strobed through the shafts of light from the dangling overheads, and the old beams groaned beneath the load of the loft. I was plenty tough, sure, but I was also a high-school sophomore and still got spooked more often than Id want to admit.

I turned to the door, my fists clenched around the wooden handles of the baling hooks. Each hook is a wicked metal curve that protrudes about a foot from between the knuckles of my hand. The barn door, now open, looked out onto darkness. The wind lashed in, cutting through my jeans and flannel shirt, carrying a reek that overpowered the scent of hay. It smelled as if someone were cooking rotten flesh.

I clutched those baling hooks like a second-rate Wolverine, cleared my throat, and stepped toward the door, doing my best to deepen my voice. Whos there?

Patrick swung into sight, his pump-action shotgun pointed at the floor. Chance, he said, thank God youre okay.

My older brothers broad chest rose and fell, his black cowboy hat seated back on his head. Hed been running, or he was scared.

But Patrick didnt get scared.

Of course Im okay, I said. What are you talking about? I let the baling hooks drop so they dangled around my wrists from the nylon loops on the handles. Covering my nose with a sleeve, I stepped outside. Whats that smell?

The wind was blowing west from McCaffertys place or maybe even the Franklins beyond.

I dont know, Patrick said. But thats the least of it. Come with me. Now.

I turned to set down my gear on the pallet jack, but Patrick grabbed my shoulder.

You might want to bring the hooks, he said.

I should probably introduce myself at this point. My name is Chance Rain, and Im fifteen. Fifteen in Creeks Cause isnt like fifteen in a lot of other places. We work hard here and start young. I can till a field and deliver a calf and drive a truck. I can work a bulldozer, break a mustang, and if you put me behind a hunting rifle, odds are Ill bring home dinner.

Im also really good at training dogs.

Thats what my aunt and uncle put me in charge of when they saw I was neither as strong nor as tough as my older brother.

No one was.

In the place where youre from, Patrick would be the star quarterback or the homecoming king. Here we dont have homecoming, but we do have the Harvest King, which Patrick won by a landslide. And of course his girlfriend, Alexandra, won Harvest Queen.

Alex with her hair the color of wheat and her wide smile and eyes like sea glass.

Patrick is seventeen, so Alex is between us in age, though Im on the wrong end of that seesaw. Besides, to look at Patrick you wouldnt think he was just two years older than me. Dont get me wrong-years of field work have built me up pretty good, but at six-two, Patrick stands half a head taller than me and has grown-man strength. He wanted to stop wrestling me years ago, because there was never any question about the outcome, but I still wanted to try now and then.

Sometimes tryings all you got.

Its hard to remember now before the Dusting, but things were normal here once. Our town of three thousand had dances and graduations and weddings and funerals. Every summer a fair swept through, the carnies taking over the baseball diamond with their twirly-whirly rides and rigged games. When someones house got blown away in a tornado, people pitched in to help rebuild it. There were disputes and affairs, and every few years someone got shot hunting and had to get rushed to Stark Peak, the closest thing to a city around here, an hour and a half by car when the weather cooperated. We had a hospital in town, better than youd think-we had to, what with the arms caught in threshers and ranch hands thrown from horses-but Stark Peaks where youd head if you needed brain surgery or your face put back together. Two years ago the three Braaten brothers took their mean streaks and a juiced-up Camaro on a joyride, and only one crawled out of the wreckage alive. You can bet Ben Braaten and his broken skull got hauled to Stark Peak in a hurry.

Our tiny town was behind on a lot. The whole valley didnt get any cell-phone coverage. There was a rumor that AT&T was gonna come put in a tower, but what with our measly population they didnt seem in a big hurry. Our parents said that made it peaceful here. I thought that made it boring, especially when compared to all the stuff we saw on TV. The hardest part was knowing there was a whole, vast world out there, far from us. Some kids left and went off to New York or L.A. to pursue big dreams, and I was always a bit envious, but I shook their hands and wished them well and meant it.

Patrick and I didnt have the same choices as a lot of other kids.

When I was six and Patrick eight, our parents went to Stark Peak for their anniversary. From what we learned later, there was steak and red wine and maybe a few martinis, too. On their way to the theater, Dad ran an intersection and his trusty Chrysler got T-boned by a muni bus.

At the funeral the caskets had to stay closed, and I could only imagine what Mom and Dad looked like beneath those shiny maple lids. When Stark Peak PD released their personals, I waited until late at night, snuck downstairs, and snooped through them. The face of Dads beloved Timex was cracked. I ran my thumb across the picture on his drivers license. Moms fancy black clutch purse reeked of lilac from her cracked-open perfume bottle. It was the smell of her, but too strong, sickly sweet, and it hit on memories buried in my chest, making them ring like the struck bars of a xylophone. When I opened the purse, a stream of pebbled windshield glass spilled out. Some of it was red.

Breathing the lilac air, I remember staring at those bloody bits scattered on the floorboards around my bare feet, all those pieces that could never be put back together. I blanked out after that, but I must have been crying, because the next thing I remember was Patrick appearing from nowhere, my face pressed to his arm when he hugged me, and his voice quiet in my ear: I got it from here, little brother.

I always felt safe when Patrick was there. I never once saw him cry after my parents died. It was like he ran the math in his head, calm and steady as always, and decided that one of us had to hold it together for both of us, and since he was the big brother, that responsibility fell to him.

Sue-Anne and Jim, my aunt and uncle, took us in. They lived just four miles away, but it was the beginning of a new life. Even though I wanted time to stay frozen like it was on Dads shattered Timex, it couldnt, and so Patrick and I and Jim and Sue-Anne started over.

Next page