CONTENTS

2. TO THE CLEARING

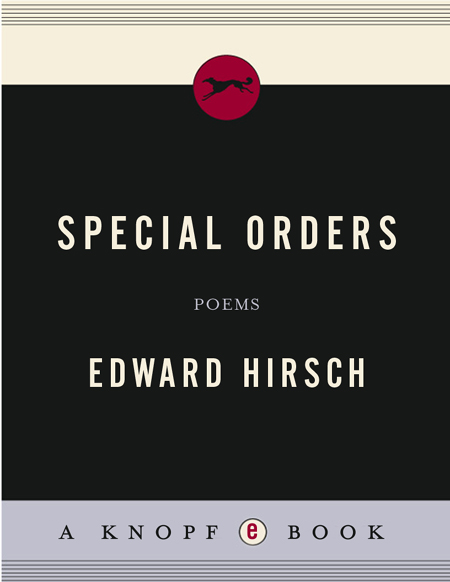

Special Orders

Give me back my father walking the halls

of Wertheimer Box and Paper Company

with sawdust clinging to his shoes.

Give me back his tape measure and his keys,

his drafting pencil and his order forms;

give me his daydreams on lined paper.

I don't understand this uncontainable grief.

Whatever you had that never fit,

whatever else you needed, believe me,

my father, who wanted your business,

would squat down at your side

and sketch you a container for it.

Cotton Candy

We walked on the bridge over the Chicago River

for what turned out to be the last time,

and I ate cotton candy, that sugary air,

that sweet blue light spun out of nothingness.

It was just a moment, really, nothing more,

but I remember marveling at the sturdy cables

of the bridge that held us up

and threading my fingers through the long

and slender fingers of my grandfather,

an old man from the Old World

who long ago disappeared into the nether regions.

And I remember that eight-year-old boy

who had tasted the sweetness of air,

which still clings to my mouth

and disappears when I breathe.

Branch Library

I wish I could find that skinny, long-beaked boy

who perched in the branches of the old branch library.

He spent the Sabbath flying between the wobbly stacks

and the flimsy wooden tables on the second floor,

pecking at nuts, nesting in broken spines, scratching

notes under his own corner patch of sky.

I'd give anything to find that birdy boy again

bursting out into the dusky blue afternoon

with his satchel of scrawls and scribbles,

radiating heat, singing with joy.

Playing the Odds

The Vegas lights are glaring at one a.m.

and I can still see my bulky first father

standing at the craps table

whispering softly to the dice,

Come on, baby, come home to Daddy.

He is surrounded by strangers who are

shouting out numbers, laying down bets,

and he is massively alone, like God

playing dice with the universe

on a felt table in a fake city.

My sister and I watch him from the crowd.

Our father wants a seven coming out.

He wants to roll dice until he can't win

anymore, and then he needs to lose.

But everyone likes him for that seven.

I was two years old when I last saw him

blowing on the dice in our kitchen.

These are the true numbers, he said,

cupping them in his palms,

and then he tossed them on the table.

I remember the sweaty warmth

of those dice before he threw them.

I wonder if God Himself

breathed into the nostrils of His son

with as much tenderness and desperation.

for Harold Rubenstein, 19282004

My Fathers Track and-Field Medal, 1932

Cup the tarnished metal in your palm.

Look closely and you'll see a squirrel

scampering up a beech-wood in the forest.

You'll see a cardinal flaming in the branches.

You'll see a fleet-footed antelope racing

through the woods ahead of the hunters.

Cold Calls

If you had watched my father,

who had been peddling boxes for fifty years,

working the phones again at a common desk,

if you had listened to him sweet-talking

the newly minted assistant buyer at Seagram's

and swearing a little under his breath,

if you had sweated with him on the docks

of a medical supply company

and heard him boasting, as I did,

that he had to kiss some strange asses,

if you had seen him dying out there,

then you would understand why I stood

at his grave on those wintry afternoons

and stared at the bare muddy trees

and raved in silence to no one,

to his name carved into a granite slab.

Cold calls, dead accounts.

Second-Story Warehouse

SUMMER 1966

Come with me to the second-story warehouse

where I filled orders for the factory downstairs,

and commanded the freight elevator, and read

high in the air on a floating carpet of boxes.

I could touch the damp pipes in the ceiling

and smell the rust. I could look over

the Puerto Rican workers in the parking lot,

smoking and laughing and kidding around

in Spanish during their break, especially Julia,

who bit my lower lip until it bruised and bled,

and taught me to roll cigarettes in another language,

and called me her virgin boy from the suburbs.

All summer I read Neruda's Canto General

and took lessons from Juan, who trained me

to accept orders with dignity dignidad

and never take any shit from the foreman.

He showed off the iron plate in his skull

from a bar fight with a drunken supervisor,

while the phone blinked endlessly from Shipping

& Handling, and light glinted off the forklift.

I felt like a piece of wavy, fluted paper

trapped between two sheets of linerboard

in the single wall, double-faced boxes

we lifted and cursed, sweated and stacked

on top of heavy wooden skids. I dreaded

the large, unwieldy industrial A-flutes

and the 565 stock cartons that we carried

in bundles through the dusty aisles

while downstairs a line of blue collars fed

slotting, gluing, and stitching machines.

Juan taught me about mailers and multidepths

and praised the torrential rains of childhood,

the oysters that hid in the bloody coral,

their pearls shimmering in the twisted rock,

green stones polished by furious storms

and coconut palms waving in the twilight.

He praised the sun that floats over the island

like a bell ringed with fire, or a sea rose,

and the secret torch that forever burns

inside us, a beacon no one can touch.

Come with me to the second-story warehouse

where I learned the difference between

RSC, FOL, die-cuts, and five-panel folders,

and saw the iron shine inside a skull.

Every day at precisely three in the afternoon

we delivered our orders to the loading dock.

We may go down dusty and tired, Juan said,

but we come back smelling like the sea.

The Swimmers

for Gerald Stern

We warbled on the muddy banks

and waded up to our throats in the Delaware River,

talking about Ovid washing himself in the Black Sea

and Paul Celan floating face-down in the Seine.