The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

Contents

More than a wake-up pill Filling the knowledge gap Specialty vs. commercial coffees

Dancing (and nondancing) goats Coffees economic paradox Coffee snobs to the rescue

Coffee stores, real and virtual What all the names mean Roast names and roast taste

What to taste for The cupping ritual demystified Grace notes and ambiguities

Choosing coffee by origin Blending and blends Flavored coffees

Coffee, people, and environment Organic, shade-grown, fair-trade, and sustainable coffees

How coffee is roasted Formula vs. eye, ear, and nose How to roast your own

Keeping it fresh Choosing the right grinder and grind

Choosing a method and a machine Brewing it right

What makes espresso espresso Espresso history Classic, beatnik, and mall espresso

How to brew the coffee, froth the milk, assemble the drinks, and find the right equipment

The social sacrament From coffee ceremony to travel mug

How coffee is grown, processed, and graded Growing your own

Public ceremonies and ritual conviviality Coffee places

Poison vs. panacea Science weighs in Decaffeinated coffees

1 INTRODUCING IT

More than a wake-up pill

Filling the knowledge gap

Specialty vs. commercial coffees

When the first edition of this book appeared in the mid-1970s, finding a good cappuccino or a bag of freshly roasted specialty coffee was an act of esoteric consumerism often requiring miles of freeway travel and penetration into select corners of large American cities. Today there seems to be a specialty coffee store on every gentrified street corner (half of them Starbucks) and an espresso machine in every restaurant.

When I sold my caff in Berkeley, California, in 1975, it was one of about five or six such establishments in the entire town and one of three putting out a decent cappuccino. Toward the end of the 1990s, there were over forty caffs on one side of the University of California campus alone, brewing close to 40,000 cups of Italian coffee a day, or 1.2 cups per student, per day, a figure that includes tea drinkers and various beverage puritans.

It would seem that the implicit theme of this book is on its way to prevailing: Coffee is a sensual experience as well as a wake-up pill, and if it is drunk at all, it should be drunk well and deliberately, rather than swilled half cold out of Styrofoam plastic cups while we work. Enjoying good coffee may not save the world, but it certainly wont hurt.

The Knowledge Gap

Nevertheless, aspiration is not always fulfillment. Every Christmas large numbers of people purchase home espresso machines and, after several rounds of thin, overextracted espresso, sell their machines at a garage sale the following summer and go back to spending too much for too little at the corner caff. And at the corner caff itself, mediocrity may reign, unchallenged by customers who lack sufficient knowledge and confidence to send back thin, bitter espressos, botched caff lattes, and dead brewed coffee.

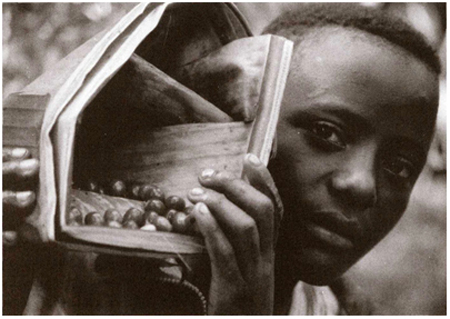

After picking, separating unripe coffee fruit from ripe in the Antigua Valley of Guatemala.

When we turn from espresso to single-origin coffees and fancy blends, the realm of Kenya AAs and Ethiopia Yirgacheffes, the gap between what most coffee-loving palates value and what their owners are able to turn up at their local coffee stores and supermarkets looms even deeper and broader. The media connoisseurship and consumer sophistication that has disciplined and given form to the fine wine industry is largely lacking for fine coffee. Charming small roasting companies spring up with wonderfully enthusiastic owners who proceed to destroy splendid green coffees by burning them. Supermarket chains replace the coffees of reputable, dependable specialty roasters with their own lines of specialty coffees that often prove to be, at best, mediocre.

Coffee lovers lack the language to impose their desires on the world, and even when they do, coffee sellers may not hear them. Recently I overheard a customer declare to a clerk in a coffee store that she did not care for acidy coffees. She then asked the clerk to recommend a less acidy coffee. These words are exactly the right words formed into the right question to get this coffee drinker exactly what she wanted. Nevertheless, the clerk could not come up with an adequate response, even though he had at least one superb low-acid coffeea Brazil Santosavailable in the bins behind him.

This book is addressed to those coffee drinkers who are interested in achieving their coffee aspirations, as well as to casual, unconverted readers who may doubt that coffee offers a world of pleasure and connoisseurship as rich and interesting as wine, although considerably more accessible. It is not another gift cookbook filled with recipes that you try once, during the week between Christmas and the New Year. It is a practical book about a small but real pleasure, with advice about how to buy better coffee, make better coffee, enjoy coffee in more ways, avoid harming yourself with too much caffeine, and, if you care to, talk about coffee with authority. Throughout, I have tried to blend the practical and experimental with the historical and descriptive, and to produce a book simultaneously useful in the kitchen and entertaining in the armchair.

A Bargain Luxury

A note on coffee cost: In the years since this book first appeared, coffee prices have fluctuated, often dramatically. But even at its most expensive, fine coffee has remained a bargain, perhaps too much of a bargain from the point of view of the growing countries. A cup of one of the worlds premier coffees today costs less than the same amount of Pepsi-Cola, and is fifteen or twenty times cheaper than a wine of the same distinction.

I sometimes think that coffee has remained inexpensive because Americans want to keep it that way. They are willing to pay for quality in coffee, but not snobbery in coffee. Whereas wine carries with it an aristocratic culture of nostalgia, Americans have insisted on keeping coffee the peoples drink, with the search for the perfect cup a quest for a holy grail that is accessible to everyone, no knighthood necessary. It often has been noted how consistently coffee has been associated with democracy in Americas cultural history. From the defiant American embrace of coffee after the Boston Tea Party to the good cup of Java refrain on the cult television series Twin Peaks, coffee has represented an arena where plain folks can pursue and recognize quality without needing to put on airs or drop a lot of cash. Coffee offers connoisseurship at a good price, without pretension.

A Perfect Cup

I used to stay at a little run-down hotel in Ensenada, Mexico, overlooking the harbor. The guests gathered every morning in a big room filled with threadbare carpets and travel posters of the Swiss Alps, to sit on broken-down couches, sip the hotel coffee, and look out at the harbor through sagging French doors.