TO MY PARENTS, LIZ AND JIM

TO MY PARENTS, LIZ AND JIM

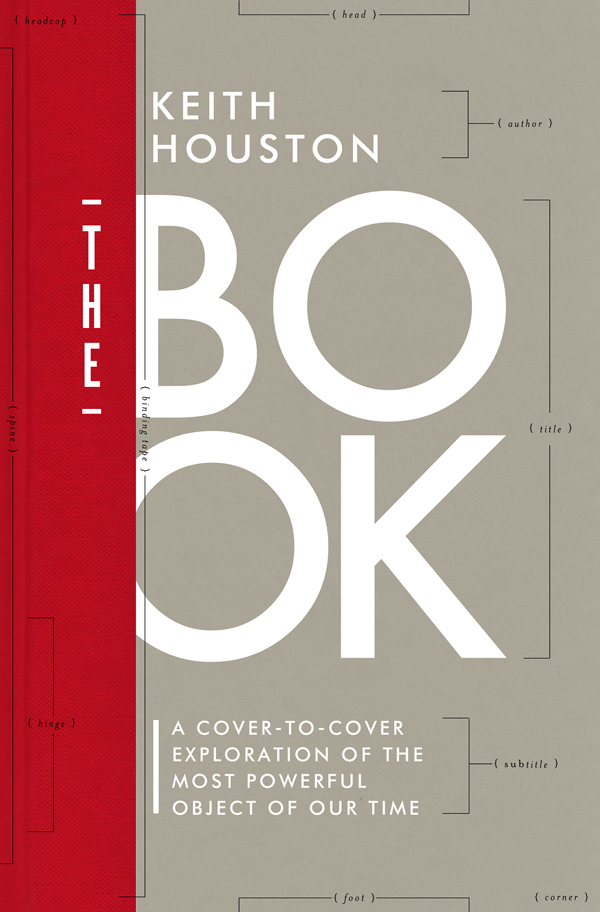

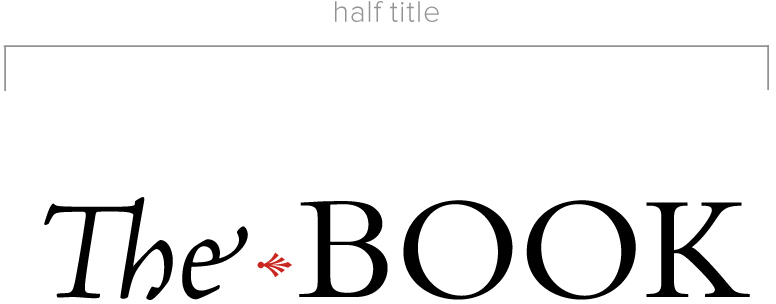

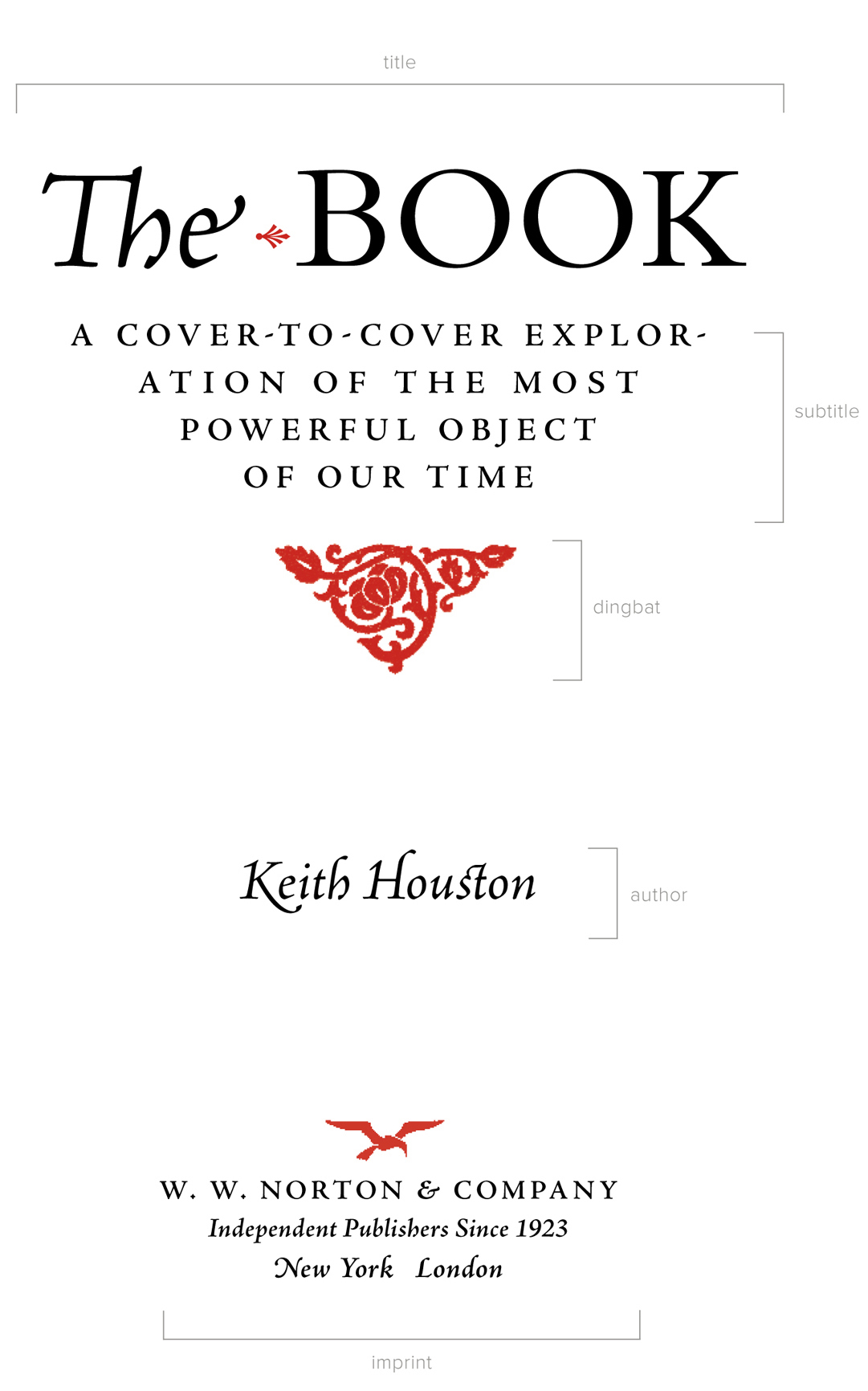

T his is a BOOK about books. Until recently, this would have been an unambiguous statement. Whether it was a flimsy paperback or a ponderous coffee-table tome, a book was a book and the word came without caveats. We bought books at bookshops and garage sales; we borrowed them temporarily from libraries and permanently from our friends (and sometimes the other way around); we held them reverently, gingerly, or forced them open until their spines cracked; we filed them neatly on bookshelves or piled them haphazardly at our bedsides. To borrow the words of Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart, we know a book when we see it.

T his is a BOOK about books. Until recently, this would have been an unambiguous statement. Whether it was a flimsy paperback or a ponderous coffee-table tome, a book was a book and the word came without caveats. We bought books at bookshops and garage sales; we borrowed them temporarily from libraries and permanently from our friends (and sometimes the other way around); we held them reverently, gingerly, or forced them open until their spines cracked; we filed them neatly on bookshelves or piled them haphazardly at our bedsides. To borrow the words of Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart, we know a book when we see it.

After more than a thousand years as the worlds most important form of written record, the book as we know it faces an unknown future. Just as paper superseded parchment, movable type put scribes out of a job, and the codex, or paged book, overtook the papyrus scroll, so computers and electronic books threaten the very existence of the physical book. E-books are cheap and convenient, weightless things downloaded at the tap of a touchscreen or the click of a mouse and effortlessly toted around in their hundreds on a phone or tablet. Barring an actual apocalypse, your e-books will be stored safely online forever, duplicated serenely across a host of servers in data centers around the world. It takes a strong will to resist the lure of the e-book.

Yet tiny apocalypses, just not of the physical variety, are happening all the time. In 2009, in an apparent attempt to carry out the worlds most ironic act of censorship, Amazon silently deleted certain editions of George Orwells 1984 from their owners Kindles as part of a copyright dispute, and news outlets continue to report on the plight of readers whose e-books have vanished without warning. When you click Buy Now to get that new title delivered to your account, you are not buying anything: the e-book economy is like a housing market where no one is allowed to buy a house and we, the tenants, remain trapped on the wrong side of the divide.

All that set aside, pluck a physical book off your bookshelf now. Find the biggest, grandest hardback you can. Hold it in your hands. Open it and hear the rustle of paper and the crackle of glue. Smell it! Flip through the pages and feel the breeze on your face. An e-book imprisoned behind the glass of a tablet or computer screen is an inert thing by comparison.

This book is not about e-books. This book is about the corporeal ones that came before them, the unrepentantly analog contraptions of paper, ink, cardboard, and glue that we have lived with and depended on for so long. It is about books that have mass and odor, that fall into your hands when you ease them out of a bookcase and that make a thump when you put them down. It is about the quiet apex predator that won out over clay tablets, papyrus scrolls, and wax writing boards to carry our history down to us.

It is, admittedly, all too easy to take the existence of physical books for granted. The sheer weight of them that surrounds us at all times, in bookcases, libraries, and bookshops, leads to a kind of bibliographic snow blindness. In writing this book I leafed through hundreds more, and even then I gave many of them barely a second glance beyond the text and illustrations on their pages. But every so often I remembered to look again, and I was amazed at what I found. One book fell open to reveal a sheet of handmade papyrus glued onto a blank page. It was the first time I had ever seen or touched a piece of this ancient ancestor of paper. The plastic-seeming material covering the spine of another book turned out to be calfskin vellum, the writing material that saw off papyrus and that was in turn usurped by paper. Some books held elaborate illustrations that had been printed using wooden blocks or copper plates, or even painted by hand; in others, pasted-in color photographs printed on glossy paper were a reminder that the printing of scenes from life has not always been as convenient as it is now. A books text can tell you something about it too, and it was a treat to come across those old books whose letters were just barely indented on the paper, the ink impressed on the page by the force of a printing press rather than wicked off an eerily flush lithographic plate. Even a humble paperback speaks volumes about bookmaking by the smell of the glue in its spine and the off-white cast of its paper.

This book is about the history and the making and the bookness of all those books, the weighty, complicated, inviting artifacts that humanity has been writing, printing, and binding for more than fifteen hundred years. It is about the book that you know when you see it.

It is worth introducing codex as a technical term: it means specifically a paged book, as opposed to a papyrus scroll, clay tablet, or any of the myriad other forms the book has taken over the millennia. It is pronounced code-ex, and its plural is codices. I have used it where a distinction must be made between a paged book and any other form.

E ver since Napoleon swept into Egypt at the tail end of the eighteenth century, ushering in the modern era of Egyptology, the outside world has thrilled to successive revelations of golden death masks and boy kings; of beautiful queens and matchless libraries; and of million-ton pyramids aligned to the points of the compass with uncanny precision.

E ver since Napoleon swept into Egypt at the tail end of the eighteenth century, ushering in the modern era of Egyptology, the outside world has thrilled to successive revelations of golden death masks and boy kings; of beautiful queens and matchless libraries; and of million-ton pyramids aligned to the points of the compass with uncanny precision.

In spite of all this, ancient Egypts most vital commodity is treated nowadays as little more than a souvenir. Papyrus, the paperlike material upon which the ancient world wrote its books and conducted its business, is every bit as Egyptian as the pyramids or mummies that have since eclipsed itand it was, in its day, considerably more impor-tant than either. The intertwined stories of paper, the page, and the book begin not with the glittering wealth of god-kings or their soaring mausoleums but with the weeds that grew abundantly along the Niles marshy shores.

Cyperus papyrus has always been an interloper in Egypt, if a welcome one. To the south, beyond the countrys borders, the banks of the White Nile and the shores of Lake Victoria, its source, are crowded by stands of papyrus sedge. Here, triangular, grasslike stems crowned by sprays of fine leaves grow from submerged roots to reach around ten feet in height.

Next page

TO MY PARENTS, LIZ AND JIM

TO MY PARENTS, LIZ AND JIM

T his is a BOOK about books. Until recently, this would have been an unambiguous statement. Whether it was a flimsy paperback or a ponderous coffee-table tome, a book was a book and the word came without caveats. We bought books at bookshops and garage sales; we borrowed them temporarily from libraries and permanently from our friends (and sometimes the other way around); we held them reverently, gingerly, or forced them open until their spines cracked; we filed them neatly on bookshelves or piled them haphazardly at our bedsides. To borrow the words of Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart, we know a book when we see it.

T his is a BOOK about books. Until recently, this would have been an unambiguous statement. Whether it was a flimsy paperback or a ponderous coffee-table tome, a book was a book and the word came without caveats. We bought books at bookshops and garage sales; we borrowed them temporarily from libraries and permanently from our friends (and sometimes the other way around); we held them reverently, gingerly, or forced them open until their spines cracked; we filed them neatly on bookshelves or piled them haphazardly at our bedsides. To borrow the words of Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart, we know a book when we see it.