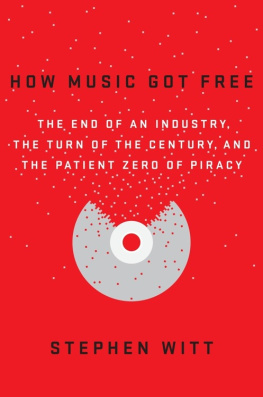

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

For my parents,

Leonard and Diana Witt

I was single, straight, and female. When I turned thirty, in 2011, I still envisioned my sexual experience eventually reaching a terminus, like a monorail gliding to a stop at Epcot Center. I would disembark, find myself face-to-face with another human being, and there we would remain in our permanent station in life: the future.

I had not chosen to be single but love is rare and it is frequently unreciprocated. Without love I saw no reason to form a permanent attachment to any particular place. Love determined how humans arrayed themselves in space. Because it affixed people into their long-term arrangements, those around me viewed it as an eschatological event, messianic in its totality. My friends expressed a religious belief that it would arrive for me one day, as if love were something the universe owed to each of us, which no human could escape.

I had known love, but having known love I knew how powerless I was to instigate it or ensure its duration. Still, I nurtured my idea of the future, which I thought of as the default denouement of my sexuality, and a destiny rather than a choice. The vision remained suspended, jewel-like in my mind, impervious to the storms of my actual experience, a crystalline point of arrival. But I knew that it did not arrive for everyone, and as I got older I began to worry that it would not arrive for me.

A year or two might pass with a boyfriend, and then a year or two without. In between boyfriends I sometimes slept with friends. After a certain number of years many of my friends had slept with one another, too. Attractions would start and end in a flexible manner that occasionally imploded in displays of pain or temporary insanity, but which for the most part functioned peacefully. We were souls flitting through limbo, piling up against one another like dried leaves, awaiting the brass trumpets and wedding bells of the eschaton.

The language we used to describe these relationships did not serve the purpose of definition. Their salient characteristic was that you had them while remaining alone, but nobody was sure what to call that order of connection. Hooking up implied that our encounters had no ceremony or civility. Lovers was old-fashioned, and we were often just friends with the people we had sex with, if not just friends. Usually we called what we did dating, a word we used for everything from one-night stands to relationships of several years. People who dated were single, unless they were dating someone. Single had also lost specificity: it could mean unmarried, as it did on a tax form, but unmarried people were sometimes not single but rather in a relationship, a designation of provisional commitment for which we had no one-word adjectives. Boyfriend , girlfriend , or partner implied commitment and intention and therefore only served in certain instances. One friend referred to a non-ex with whom he had carried on a nonrelationship for a year.

Our relationships had changed but the language had not. In speaking as if nothing had changed, the words we used made us feel out of sync. Many of us longed for an arrangement we could name, as if it offered something better, instead of simply something more familiar. Some of us tried out neologisms. Most of us avoided them. We were here by accident, not intention. Whatever we were doing, nobody I knew referred to it as a lifestyle choice. Nobody described being single in New York and having sporadic sexual engagement with a range of acquaintances as a sexual identity. I thought of my situation as an interim state, one that would end with the arrival of love.

* * *

The year I turned thirty a relationship ended. I was very sad but my sadness bored everyone, including me. Having been through such dejection before, I thought I might get out of it quickly. I went on Internet dates but found it difficult to generate sexual desire for strangers. Instead I would run into friends at a party, or in a subway station, men I had thought about before. That fall and winter I had sex with three people, and kissed one or two more. The numbers seemed measured and reasonable to me. All of them were people I had known for some time.

I felt happier in the presence of unmediated humans, but sometimes a nonboyfriend brought with him a dark echo, which lived in my phone. It was a longing with no hope of satisfaction, without a clear object. I stared at rippling ellipses on screens. I forensically analyzed social media photographs. I expressed levity with exclamation points, spelled-out laughs, and emoticons. I artificially delayed my responses. There was a great posturing of busyness, of not having noticed your text until just now. It annoyed me that my phone could hold me hostage to its clichs. My goals were serenity and good humor. I went to all the Christmas parties.

The fiction that I was pleased with my circumstances lasted from fall into the new year. It was in March, the trees skeletal but thawing, when a man called to suggest that I get tested for a sexually transmitted infection. Wed had sex about a month before, a few days before Valentines Day. I had been at a bar near his house. I had called him and he met me there. We walked back through empty streets to his apartment. I hadnt spent the night or spoken to him since.

He had noticed something a little off and had gotten tested, he was saying. The lab results werent back but the doctor suspected chlamydia. At the time we slept together he had been seeing another woman, who lived on the West Coast. He had gone to visit her for Valentines Day, and now she was furious with him. She accused him of betrayal and he felt like a scumbag chastised for his moral transgression with a disease. Hed been reading Joan Didions essay On Self-Respect. I laughedit was her worst essaybut he was serious. I said the only thing I could say, which was that he was not a bad person, that we were not bad people. That night had been finite and uncomplicated. It did not merit so much attention. After we hung up I lay on the couch and looked at the white walls of my apartment. I had to move soon.

I thought the phone call would be all but then I received a recriminatory e-mail from a friend of the other woman. I am surprised by you, it said. You knew he was going to see someone and didnt let that bother you. This was true. I had not been bothered. I had taken his seeing someone as reassurance of the limited nature of our meeting, not as a moral test. I would advise that you examine what you did in some cold, adult daylight, wrote my correspondent, who further advised me to stop pantomiming thrills and starkly consider the real, human consequences of real-life actions.

The next day, sitting in the packed waiting room of a public health clinic in Brooklyn, I watched a clinician lecture her captive, half-asleep audience on how to put on a condom. We waited for our numbers to be called. In this cold, adult daylight, I examined what I had done. A single persons need for human contact should not be underestimated. Surrounded on all sides by my imperfect fellow New Yorkers, I thought many were also probably here for having broken some rules about prudent behavior. At the very least, I figured, most people in the room knew how to use condoms.

The clinician responded with equanimity to the occasional jeers from the crowd. She respectfully said no when a young woman asked if a female condom could be used in the butt. After her lecture, while we continued to wait, public health videos played on a loop on monitors mounted on the wall. They dated from the 1990s, and dramatized people with lives as disorderly as mine, made worse by the outdated blue jeans they wore. The brows of these imperfect people furrowed as they accepted diagnoses, admitted to affairs, and made confessional phone calls on giant cordless phones. Men picked each other up in stage-set bars with one or two extras in fake conversation over glass tumblers while generic music played in the background to signify a party-like atmosphere, like porn that never gets to the sex. They later reflected on events in reality-television-style confessional interviews. From our chairs, all facing forward in the same direction, awaiting our swabbing and blood drawing, we witnessed the narrative consequences. (One of the men at the gay bar had a girlfriend at home and gonorrhea. We watched him tell his girlfriend that he had sex with men and that he had gonorrhea.) The videos did not propose long-term committed relationships as a necessary condition of adulthood, just honesty. They did not recriminate. The New York City government had a technocratic view of sexuality.

Next page