Rex Stout

Death Times Three

Death Times Three is a collection of Nero Wolfe novellas by Rex Stout, published posthumously by Bantam Books in 1985. It is the only collection of Stout's Nero Wolfe stories not to have appeared first in hardcover. The book contains three stories, one never before published:

Bitter End, first printed in the November 1940 issue of The American Magazine, and collected in the limited-edition volume Corsage: A Bouquet of Rex Stout (1977). The story is a re-working of Stout's Tecumseh Fox story Bad for Business.

Frame-Up for Murder, an expanded rewrite of the 1958 novella Murder Is No Joke that was serialized in three issues of The Saturday Evening Post (June 21, June 28 and July 5, 1958) but never published in book form.

Assault on a Brownstone, an early draft of the 1961 novella Counterfeit for Murder; in this draft, Hattie Annis, who would become one of the most carefully drawn and favorite non-recurring Nero Wolfe characters in the revised, renamed published version, is the murder victim, while Tammy survives and has an implied romantic relationship with Archie.

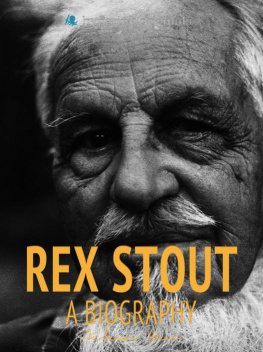

During the last years of Rex Stouts life, as his authorized biographer, I received numerous letters from well-wishers and, on occasion, not-such-well-wishers, offering me advice. Is it true, one of the latter asked, that Stout has a secretary who writes all his stuff for him? I showed the letter to Rex, then in his eighty-ninth year. He scanned it and said, Tell him the name is Jane Austen, but I havent the address. The joke was on the letter writer. Rex was classing himself with the best. Not long before that he had told me, I used to think that men did everything better than women, but that was before I read Jane Austen. I dont think any man ever wrote better than Jane Austen.

It was no coincidence that, when I asked after Wolfe a few days before Rex died, Rex confided, Hes rereading Emma. Rex ranked Emma as Jane Austens masterpiece. In the last weeks of his life he also reread it. That a book could be reread was to him solid proof of its worth. Thus it pleased him when P. G. Wodehouse, whom Rex admired, declared, at ninety-four, in a letter that he wrote to me, He [Rex Stout] passes the supreme test of being rereadable. I dont know how many times I have reread the Nero Wolfe stories, but plenty. I know exactly what is coming and how it is all going to end, but it doesnt matter. Thats writing.

Since Rexs death, on October 27, 1975, the radiant host that constitutes his loyal following has reread many times the thirty-three novels and thirty-eight novellas believed to make up the entire corpus of the Wolfe saga. How jubilant must be this worldwide audience to learn now that many new pages of reading pleasure await it a thirty-ninth novella, Bitter End, known only to a smattering of readers; Frame-Up for Murder, a substantially expanded rewrite of Murder Is No Joke, the existence of which has gone unsuspected by most Stout readers since it has never before appeared in book form; and a fortieth novella, the original version of Counterfeit for Murder, which, after the first seven pages, pursues a plot line that differs markedly from what followed in the version eventually published in Homicide Trinity (1962). The existence of this unpublished manuscript was unknown, even to members of Rex Stouts own family, until 1972, when Rex furnished me a handwritten copy of his personal Writing Record, in which the facts relating to its composition were recorded. A diligent search among his voluminous papers, at Boston Colleges Bapst Library, when they were delivered to the college following his death, disclosed that, contrary to his remembrance, he had not destroyed this manuscript and that there was, therefore, a seventy-third Nero Wolfe story that had never seen print. This discovery surpasses in significance the publication in 1951, for the first time in the United States of the fifty-first Father Brown story, The Vampire of the Village, and the publication in 1972, for the first time anywhere of Talboys, a hitherto unknown Lord Peter Wimsey story; it is on a par only with the discovery of an eightieth Sherlock Holmes story an event which has not yet occurred.

For admirers of Nero Wolfe and Archie Goodwin, in the years between 1934 and 1975, the advent of a new Nero Wolfe story was ever an occasion for rejoicing. However, because the stories appeared with unfailing regularity (save for the years of World War II, when Rex Stout was heading up Americas propaganda effort as chairman of the Writers War Board), the thrill probably came to be regarded by many as theirs by right of entitlement. For a bona fide new story to come to light, after every legitimate hope for such an event had been relinquished, constitutes an occasion that must set the firmament ablaze with pyrotechnical wonders. What a windfall! What a gift from the stars! Yet, here we have, in this single volume, not only such a treasure, but two other Nero Wolfe tales largely new to us. None of the three, moreover, can be dismissed as a mere practice exercise, sketched out and flung aside by Rex Stout as beneath his standards. Each piece is carefully wrought; each is from a period when he was in top writing form; each contains incomparable moments, insights, and sallies of wit that will take their place in the memories of votaries of the corpus as new pinnacles in a landscape already wondrously sown with pinnacles. Let us consider each in its turn.

Bitter End, published in The American Magazine in November 1940, was the first of what we now know to be forty Nero Wolfe novellas. But it began life not as a Nero Wolfe novella but as a Tecumseh Fox novel. In 1939, to accommodate his publishers, who had asked him to create another detective to spell Wolfe, Rex introduced Tecumseh Fox in Double for Death. Fox was not the superman Wolfe was, nor did he have Archies panache, but he did have brains and muscle and, without the advantage of a dogsbody to assist him, he worked out the solution to an intricate case. Rexs friends thought Fox was rather like Rex himself. Certainly, like Rex, he was on the move a lot. That was inevitable. Rex said he had made Wolfe housebound because other peoples detectives ran around too damn much. Yet he realized that two sedentary detectives would be too limiting.

In the summer of 1940 Rex was ready with a second Fox novel Bad for Business. Farrar & Rinehart scheduled it for publication in November of that year in its Second Mystery Book, where it was to be the culminating tale in a volume that would include stories by Anthony Abbot, Philip Wylie, Leslie Ford, Mary Roberts Rinehart, and David Frome (a Leslie Ford alias) Bad for Business though, weighing in at two hundred and five pages, was far and away the longest. As was customary, the story was offered to The American Magazine for abridged publication before the book itself appeared. To Stouts surprise, Sumner Blossom, publisher of The American Magazine, refused to pursue the Fox piece but offered Stout double payment if he would convert the story into a Wolfe novella. To Blossoms surprise, and maybe his own, Rex effected the transformation in eleven days. As he explained to me later, by then he had already become deeply committed to the war against Hitler and needed the money.

Thus Bitter End, Rexs first Wolfe novella, appeared in The American Magazine in November 1940 and on November 28, Bad for Business appeared in the Second Mystery Book. Those who read both stories at that time must have been perplexed. The plot was basically unchanged. The names of the principal characters likewise were the same. This was true as well of many lines of dialogue and of many crucial expository passages. Yet, Tecumseh Foxs labors had been portioned out between Wolfe and Archie; Foxs nemesis from Homicide, Inspector Damon, had been supplanted, inevitably, by Inspector Cramer; and Dol Bonner, whose path occasionally crossed Foxs in