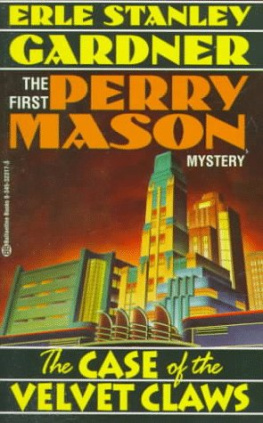

Erle Stanley Gardner

The Blonde in Lower Six

The Blonde in Lower Six, Argosy, September 1961

The Wax Dragon, Black Mask, November 1927

Grinning Gods, Black Mask, December 1927

Yellow Shadows, Black Mask, February 1928

It was a night when swirling fog scurried over the high peaks of San Francisco, to settle down in the comparatively windless tranquillity over Chinatown. Having hurried in from the ocean, the fog now became leisurely, settling down slowly upon the carved dragons, the distinctive roofs with their peculiar upturned corners down to the level of the second- and third-story windows and stopping.

As I emerged from the Stockton Street Tunnel, I couldnt help noticing this vagary of the fog and wondering about the reason for it. So many nights I had seen the fog rush breathlessly in over the peaks, pause to hover over Chinatown, then settle to a point where the red neon signs gave it the appearance of fine blood particles suspended in the air in little ominous eddies and down on the sidewalks there would be no fog at all, only a peculiar hush, a dampness and a menace.

Behind me, lay the city of San Francisco, modem, up-to-date, plagued with those problems which are brought about by the complexities of civilization. Ahead of me was a section which, so far as the eye could tell, might well have been eight thousand miles away a section of old Cathay. San Franciscos Chinatown is like that, and the line of demarcation is as sharp as though it had been etched with the blade of a keen dagger.

When one is being used by the police as a convenient scapegoat upon whom to blame unsolved crimes, it behooves one to be careful. And when one has, moreover, incurred the enmity of the organized underworld, it behooves one to be doubly careful. But tonight I had an even greater incentive to seek the dark byways. I was calling on Soo Hoo Duck, the king of Chinatown.

There was a time when one who had the proper credentials needed only to pass the point where San Franciscos ornamental street lights became crested with dragons, the sign of the beginning of Chinatown, to go about carrying on the business of Soo Hoo Duck with absolute impunity.

Now, with the war, there were spying eyes and listening ears. There were those who would give much to learn, even to within a block, the nerve center from which the activities of organized Chinatown are conducted. One bomb dropped from a submarine-borne airplane, or perhaps skillfully planted in an adjoining building would have done much to wreck the Chinese espionage system.

I entered a narrow alley. Only too well I realized the dangers which might lurk here, but I realized also that no one could follow me into this alley without my knowing it.

I walked half the length of the alley and waited.

The fog-filled silence was broken by the occasional moaning of fog signals from the bay. The muted noises of the city, merged by distance into a continuous murmur of sound, were not loud enough to be audible unless one deliberately listened.

As the sound of my breathing became more quiet, I could hear the steady, monotonous drip... drip... drip of moisture from the eaves of the houses.

There was no sound that would indicate the presence of any other human being.

Years of practice in threading my way through the darkness stood me in good stead. Long before any of us knew what vitamins were, the eating of carrots to enable one to see at night was one of the most carefully guarded secrets of the underworld. I counted doorways, paused before an innocent-appearing door, opened it and entered a smelly little passageway. The door swung shut behind me and I was in darkness so intense that it was difficult to keep even a sense of direction. I waited a full five minutes. Then I walked slowly through the smelly darkness, perhaps a hundred feet. Again I waited cautiously.

When I opened the door that was now barring my way, I was in a crowded anteroom, merely one human atom in a composite whole, a stream of packed humanity that was flowing ever forward toward the lighted stage of a Chinese theater.

Cymbals clashed.

A thin, reedy note of a Chinese flute snarled at the auditory nerve, screaming, at times, into a pitch of sound so high that it was all but inaudible.

The stage at the front of the theater held no curtain, no scenery. It was merely a raised platform containing three or four chairs, a large table, a small table and a couple of stools. The Chinese feel that imagination is a rare attribute, something to be cultivated, and so they refrain from giving an audience all the facilities the occidental theatergoer has learned to require before his imagination can visualize that which is happening on the stage in terms of actuality.

The Chinese flute skirled into a new ecstasy of sound. The cymbals clashed again.

A player walked out on the stage, strutting with that exaggerated swing which characterizes the Chinese actor. He was portraying a military hero.

A hand touched me on the shoulder.

An old Chinese, stooped and palsied, let his yellowed talon slip carelessly down my arm, then turned and wormed his way through the crowded darkness. I followed, taking advantage of that moment when the attention of all spectators was on the stage.

A few seconds later, I was groping through dark underground passageways. Doors opened and closed. Sliding panels moved back so that shrewd eyes could size me up as I passed, until I came at length to that familiar flight of stairs with the door at the top a steel-cored door that seemed to be a particularly flimsy portal of checked wood, the varnish dark with age and grimed with dirt.

The door swung open on massive ball-bearing hinges and Ngat Toy was waiting on the threshold to greet me.

Ed Jenkins! she said. Just two words, but the tone of her voice spoke volumes.

I entered. The door whooshed shut behind me.

She gave me her hand, a hand so long and slim and fragile that instinctively one touched it as one would hold the petal of a flower.

Its been a long time, I said.

Too long, she told me.

For a moment, her face held that inscrutable expression of oriental impassivity which is the property of a race that can mask its feelings; then she was laughing up at me. Full red lips parted to show teeth that were as pearls in a setting of rare old ivory, eyes that might have been covered with black lacquer eyes that glistened with vitality. It was nice of you to come. Must you wait for a summons?

My presence brings danger, Little Sun, I said, using the American translation of her name.

Danger! she said scornfully. Since when, she asked, has Ed Jenkins become afraid of danger?

My fear, I said, is for you.

Of a sudden, the smile faded from her face. My race does not fear danger, because it has never had security. For centuries your people have basked in security and therefore fear danger. But as for us we have never known anything but danger floods, famine, pestilence, marauders, conquerors. Death is always jeering at our elbow. Therefore, we do not fear danger nor do we fear death.

And she was right. One never knows a Chinese to worry. That is because, as a race, they are threatened with so many potential misfortunes it would be impossible to catalogue them all, let alone fear them, and worry is but an attenuated fear, long drawn-out, clutching constantly at the mind.

What, I asked, is new?

Father wants you to do something as a favor to him. It is something very, very important.

So far as I am concerned, it is done, I said.

Wait until you hear what it is.

Do you know?

Her eyes were mischievous. I do but Im not supposed to tell.

Give me a hint, Ngat Toy.