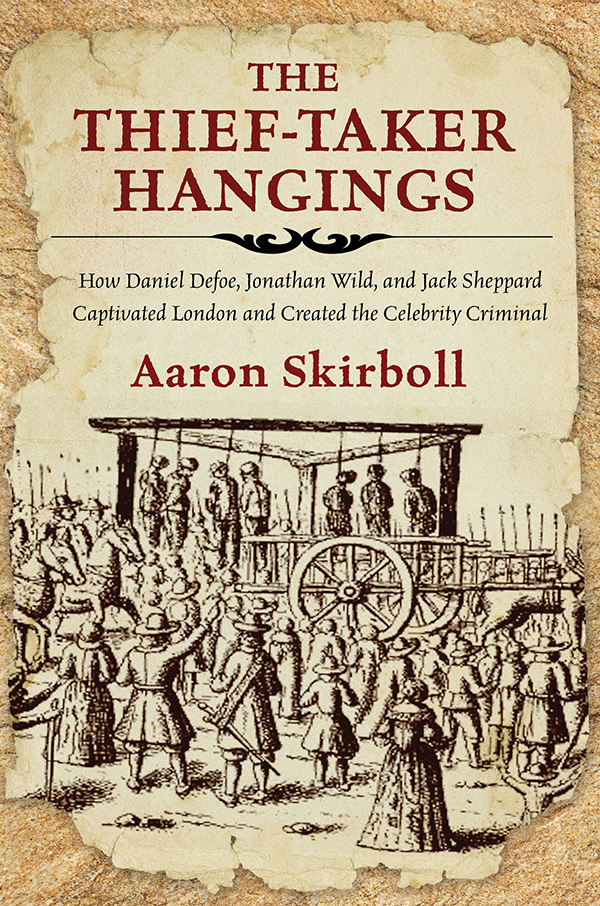

The

Thief - Taker

Hangings

The

Thief-Taker

Hangings

How Daniel Defoe, Jonathan Wild, and Jack Sheppard Captivated London and Created the Celebrity Criminal

Aaron Skirboll

For Hank

Copyright 2014 by Aaron Skirboll

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, except as may be expressly permitted in writing from the publisher. Requests for permission should be addressed to Globe Pequot Press, Attn: Rights and Permissions Department, PO Box 480, Guilford, CT 06437.

Lyons Press is an imprint of Globe Pequot Press.

Project Editor: Lauren Brancato

Layout: Melissa Evarts

Text design: Sheryl P. Kober

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Skirboll, Aaron, author.

The thief-taker hangings : how Daniel Defoe, Jonathan Wild, and Jack Sheppard captivated London and created scandal journalism / Aaron Skirboll.

pages cm

Summary: Chronicles the invention of scandal journalism by Daniel Defoe, author of Robinson Crusoe Provided by publisher.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-7627-9148-4 (hardback)

1. Crime and the pressGreat Britain18th century. 2. Sensationalism in journalismGreat BritainHistory18th century. 3. CriminalsEnglandLondonHistory18th century. 4. Tabloid newspapersGreat BritainHistory18th century. 5. London (England)Social conditions18th century. 6. Defoe, Daniel, 1661?-1731. 7. Wild, Jonathan, 1682?-1725. 8. Sheppard, Jack, 1702-1724. I. Title.

PN5124.C74S55 2014

070.4'493649421dc23

2014018791

eISBN 978-1-4930-1423-1 (eBook)

The Annals of Criminal Jurisprudence... present tragedies of real life often heightened in their effect by the grossness of the injustice and the malignity of the prejudices which accompanied them. At the same time real culprits as original characters stand forward on the canvas of humanity as prominent objects for our special study.

Edmund Burke, Celebrated Trials and Remarkable Cases of Criminal Jurisprudence

The introduction of detailed realism into English literature in the eighteenth century was like the introduction of electricity into machine technology.

Tom Wolfe, The New Journalism

English Currency in the Eighteenth Century

4 farthings = 1 penny

12 pence (d.) = 1 shilling (s.)

5 shillings = 1 crown

6 shillings, 8 pence = 1 noble

13 shillings, 4 pence = 1 mark

20 shillings = 1 pound ( or l.)

1 pound, 1 shilling = 1 guinea (gold coin)

Source: http://www.oldbaileyonline.org/static/Coinage.jsp

Contents

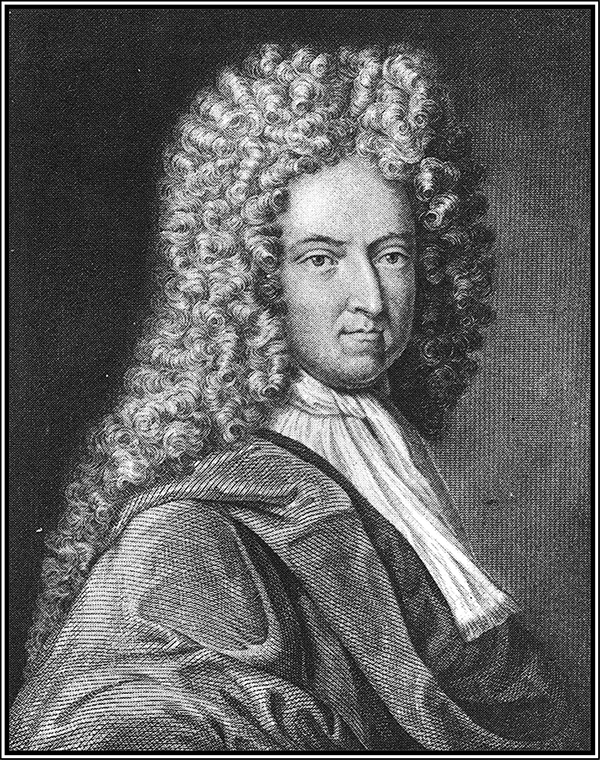

Daniel Defoe

Engraving by Michael Vandergucht after a portrait by Jeremiah Taverner

Introduction

A Brawling Back-Alley Bunch

Perhaps the first true modern literary journalist: Daniel Defoe, whose 1725 tract on the criminal Jonathan Wild offers a prototype of the modern true-crime narrative.

Kevin Kerrane and Ben Yagoda, The Art of Fact

Today criminal investigations rule the media. Once or twice each year, a trial transfixes the public, a new cause clbre born seemingly each season. Spectators travel hours to courthouses; tickets to trials are distributed by lottery; and the term media circus , coined in the 1970s, comes into its own.

If it bleeds, it leadsso goes the old journalistic saw. Readers and viewers cant tear their eyes away from true crime stories, and the grislier the details, the better. But when did it all begin, this mixing of criminal and celebrity? Searching for the origin of the phenomenon took me back three centuries to the nascent years of the newspaper and across the Atlantic to London. In the middle of it all stood Daniel Defoe, a wily old newspaperman and the aging author of Robinson Crusoe , who battled for the scoop amid the muck and grime of the eighteenth century. His coverage of two menJonathan Wild, the chaser, and Jack Sheppard, the markenthralled a kingdom and birthed a genre.

An eighteenth-century Al Capone, Jonathan Wild was the first man to organize crime for profit and the first criminal whose name everyone in the city knew. A burglar and a prison breaker, Jack Sheppard had much in common with John Dillinger. In late 1724, a manhunt for him grabbed the citys attention like no other story and drove newspaper sales skyward. Sheppard the housebreaker ran, thief-taker Wild chased him, and reporter Defoe wrote about both.

With Sheppard on the loose, the story evolved in real time, but nothing about the case was clear-cut, nor was it easy to know for whom to root. The grandeur of the once-popular hunter was fading, and the criminal was incorrigible and eminently quotable. In the middle of it all, we have a man known today primarily as a novelist, his skills as a journalist mostly forgotten. His colorful tales about the pair teemed with details, but as with nearly everything he wrote, his name was nowhere to be found, and in Sheppards case, Defoe wrote his account of the mans deeds as if it were the thiefs autobiography, as hed done with Robinson Crusoe and Moll Flanders.

In 1724 and 1725, more than thirty unsigned pamphlets were published on Wild and Sheppard. Five of these tracts have been attributed to Defoe, and the British Library has cataloged them under his name. In the story ahead, I privileged only the two pamphlets that have met with near universal agreement on the attribution to Defoe: The True and Genuine Account of the Life and Actions of the Late Jonathan Wild and A Narrative of All the Robberies, Escapes, &c. of John Sheppard. A third, The History of the Remarkable Life of John Sheppard, was probably part of a group effort in which Defoe had a hand, among others.

Entering the world of Defoe scholars with virgin eyes, I had no idea what awaited me. This is one brawling back-alley bunch of bibliophiles, many waging pissing matches to see who knows Daniel best. One camp of scholars charges another with corpus swelling, while the latter assails the former for deflating the number so as to remove works of lesser quality. In Defoes day, it was more the exception than the rule to put your name to pamphlets, so attribution makes for a thorny issue, and with over five hundred works credited to him, theres no definitive universal agreement here. Nonetheless, the scholarly scrap proved entertaining. Among those whove studied the man, its a no-holds-barred, back-and-forth assault complete with name calling. Academic insults fly to and fro: simpletons or rascals, lack of brains, a disaster. Charges of canon forgery and power moves have been made, and as one set of authors answered a particular onslaught, they decided it would look craven if we do not give him one or two backthough a Forum may not really be the place for fist-fights.

To an outsider, for the most part, more of a consensus appears about the Wild and Sheppard pamphlets credited to Defoe than not. If only it werent for the Law Firm. Thats the collective nickname I have given to scholars P. N. Furbank and W. R. Owens, who seem to want something close to DNA evidence before ascribing anything to Defoe. In their book, Defoe De-Attributions , theyve called into question some 252 of the works in Defoes canon, including many of his criminal tracts. The vast majority of Defoe biographers and others whove studied the period have kept Defoes criminal pamphlets and his work at Applebees Original Weekly Journal under his name. As Maximillian Novak, who has studied Defoe for most of his life and penned the Defoe entry in the New Cambridge Bibliography of English Literature , noted of the authors work at Applebees it was an accepted fact by every Defoe scholar until 1997. In that year, P. N. Furbank and W. R. Owens published an essay with the title The Myth of Defoe As Applebees Man.