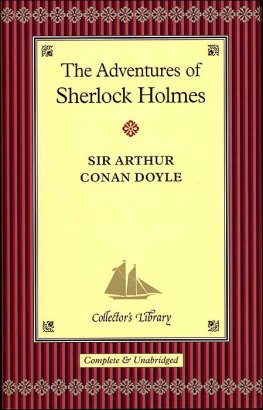

As everybody knows, Dr. Watson stored in a battered tin dispatch-box his manuscripts concerning the unpublished cases of Sherlock Holmes. This box was placed in the vaults of the bank of Cox and Co. at Charing Cross. Whatever hopes the world had that these papers would some day become public were destroyed when the bank was blasted into fragments during the bombings of World War II. It is said that Winston Churchill himself directed that the ruins be searched for the box but that no trace of it was found.

I am happy to report that this lack of success is no cause for regret. At a time and for reasons unknown, the box had been transferred to a little villa on the south slope of the Sussex Downs near the village of Fulworth. It was kept in a trunk in the attic of the villa. This, as everybody should know, was the residence of Holmes after he had retired. It is not known what eventually happened to the Greatest Detective. There is no record of his death. Even if there were, it would be disbelieved by the many who still think of him as a living person. This almost religious belief thrives though he would, if still alive, be one hundred and twenty years old at the date of writing this foreword.

Whatever happened to Holmes, his villa was sold in the late 1950s to the seventeenth Duke of Denver. The box, with some other objects, was removed to the ducal estate in Norfolk. His Grace had intended to wait until after his death before the papers would be allowed to be published. However, His Grace, though eighty-four years old now, feels that he may live to be a hundred. The world has waited far too long, and it is certainly ready for anything, no matter how shocking, that may be in Watsons narratives. The duke has given his consent to the publication of all but a few papers, and even these may see print if the descendants of certain people mentioned in them give their permission. Gratitude is due His Grace for this generous decision.

On hearing the good news, your editor communicated with the British agents handling the Watson papers and was fortunate enough to acquire the American Agency for them. The adventure at hand is the first to be released; others will follow from time to time.

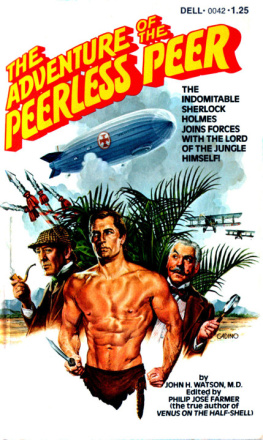

Watsons holograph is obviously a first draft. A number of passages recording words actually uttered by the participants during this adventure are either crossed out or replaced with asterisks. The peerless peer of this tale is called Greystoke, but on one occasion old habit broke through and Watson inadvertently wrote Holdernesse. Watson left no note explaining why he had substituted one pseudotitle for another. He used Holdernessee in The Adventure of the Priory School to conceal the identity of Holmes noble client. Holmes himself, in his reference to the nobleman in his The Adventure of the Blanched Soldier, used the pseudotitle of Greyminster.

It is your editors guess that Watson decided on Greystoke in this narrative because the pseudotitle had been made world-famous by the novels based on the African exploits of the nephew of the man Watson had called Holdernesse.

The adventure at hand is singular for many reasons. It reveals that Holmes was not allowed to stay in retirement after the events of His Last Bow. We are made aware that Holmes made a second visit to Africa, going far beyond Khartoum (though not willingly), and so saved Great Britain from the greatest danger which has ever threatened it. We are given some illumination on the careers of the two greatest American aviators and spies in the early years of World War I. We learn that Watson was married for the fourth time, and the destruction of a civilization rivaling ancient Egypt is recorded for the first time. Holmes contribution to apiology and how he used it to save himself and others is related herein. This narrative also describes how Holmes genius at deduction enabled him to clear up a certain discrepancy that has puzzled the more discerning readers of the works of Greystokes American biographer.

Some aspects of this discrepancy are revealed by Lord Greystoke himself in Extracts from the Memoirs of Lord Greystoke, Mother Was a Lovely Beast, Philip Jos Farmer, editor, Chilton, October, 1974. However, this revelation is only a minor part of Watsons chronicle, one among many mysteries solved, and this account presents the mystery from a somewhat different viewpoint.

Your editor decided for these reasons to leave this explanation in this work. Besides, your editor would not dream of tampering with any part of the Sacred Writings.

Philip Jos Farmer

It is with a light heart that I take up my pen to write these the last words in which I shall ever record the singular genius which distinguished my friend Sherlock Holmes. I realise that I once wrote something to that effect, though at that time my heart was as heavy as it could possibly be. This time I am certain that Holmes has retired for the last time. At least, he has sworn that he will no more go a-detectiving. The case of the peerless peer has made him financially secure, and he foresees no more grave perils menacing our country now that out great enemy has been laid low. Moreover, he has sworn that never again will he set foot on any soil but that of his native land. Nor will he ever again get near an aircraft. The mere sight or sound of one freezes his blood.

The peculiar adventure which occupies these pages began on the second day of February, 1916. At this time I was, despite my age, serving on the staff of a military hospital in London. Zeppelins had made bombing raids over England for two nights previously, mainly in the Midlands. Though these were comparatively ineffective, seventy people had been killed, one hundred and thirteen injured, and a monetary damage of fifty-three thousand eight hundred and thirty-two pounds had been inflicted. These raids were the latest in a series starting the nineteenth of January. There was no panic, of course, but even stout British hearts were experiencing some uneasiness. There were rumours, no doubt originated by German agents, that the Kaiser intended to send across the channel a fleet of a thousand airships. I was discussing this rumour with my young friend, Dr. Fell, over a brandy in my quarters when a knock sounded on the door. I opened it to admit a messenger. He handed me a telegram which I wasted no time in reading.

Great Scott! I cried.

What is it, my dear fellow? Fell said, heaving himself from the chair. Even then, on war rations, he was putting on overly much weight.

A summons to the F.O., I said. From Holmes. And I am on special leave.

Sherlock? said Fell.

No, Mycroft, I replied. Minutes later, having packed my few belongings, I was being driven in a limousine toward the Foreign Office. An hour later, I entered the small austere room in which the massive Mycroft Holmes sat like a great spider spinning the web that ran throughout the British Empire and many alien lands. There were two others present, both of whom I knew. One was young Merrivale, a baronets son, the brilliant aide to the head of the British Military Intelligence Department and soon to assume the chieftainship. He was also a qualified physician and had been one of my students when I was lecturing at Barts. Mycroft claimed that Merrivale was capable of rivalling Holmes himself in the art of detection and would not be far behind Mycroft himself. Holmes reply to this needling was that only practise revealed true promise.

I wondered what Merrivale was doing away from the War Office but had no opportunity to voice my question. The sight of the second person there startled me at the same time it delighted me. It had been over a year since I had seen that tall, gaunt figure with the greying hair and the unforgettable hawklike profile.