Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC 29403

www.historypress.net

Copyright 2014 by Dave Shampine and Daniel T. Boyer

All rights reserved

Images are courtesy of the Watertown Daily Times unless otherwise noted.

First published 2014

e-book edition 2014

ISBN 978.1.62584.774.4

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Shampine, Dave.

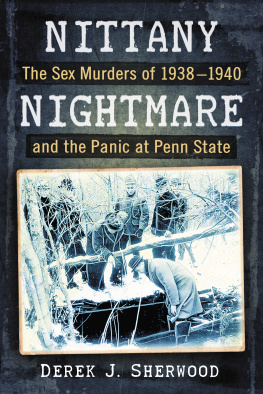

The Jefferson County Egan murders : nightmare on New Years eve, 1964 / Dave Shampine, Daniel Boyer.

pages cm

print edition ISBN 978-1-62619-288-1 (paperback)

1. Murder--New York (State)--Jefferson County--History--Case studies. 2. Murderers--New York (State)--Jefferson County--History--Case studies. I. Boyer, Daniel. II. Title.

HV6533.N5S528 2014

364.152309747--dc23

2014032541

Notice : The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the authors or The History Press. The authors and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

The authors dedicate this work in memory of

Ruth Boyer

19112012

Toby Donovan

19591989

Lucille Collier Shampine

19492012

CONTENTS

PREFACE

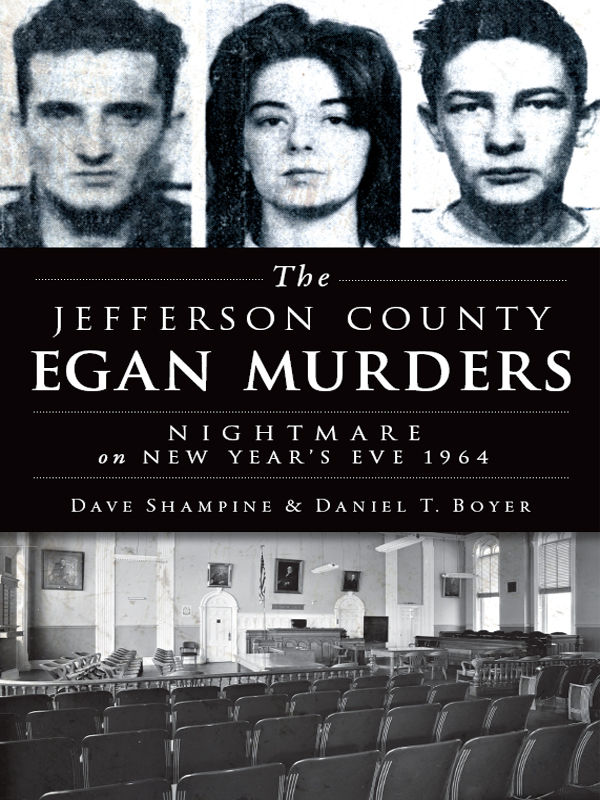

Just about everybody between the ages of 55 and 105 in New Yorks Jefferson County remembers New Years Eve 1964. They might not remember where they were celebrating, or with whom they celebrated, but they most certainly remember the heinous events that took place on that cold, dark night fifty years ago. What happened at a desolate rest area sent shock waves throughout northern New York.

Not everybody was out partying and having a good timeespecially not Peter Egan, twenty-seven; his pretty wife Barbara, twenty-four; and Peters younger brother, Gerald, nineteen. They had planned on celebrating New Years Eve later with friends at a local bowling alley, but first, they had some important business to attend to. Illegal business.

In the waning hours of 1964, the three were found dead, all with two bullets fired into their heads.

Even with their plans for the evening, the Egans and their associates had been starting to feel some heat. The Federal Bureau of Investigation had agents in Watertown, New York, working an auto theft investigation that reached all the way down the East Coast to Florida. A stolen vehicle had been found in a barn just outside Watertown, and Peter Egan was a suspect in the probe.

Might Peter start talking to the authorities and spill the beans on his accomplices about that and other crimes? He knew enough to put them all away in prison for several years.

As Peter and Barbara, the parents of three, and Gerald headed out on that fateful evening, it was business as usual for them. They were old pros when it came to burglary and theft, and they were no strangers to police. It was likely no surprise to local authorities that in the new year of 1965, the 175 or so burglaries in Watertown was a significant drop from about 400 the previous year, when the Egans were up to their shenanigans.

They were brazen, hardcore thievesbrazen enough to steal from their partners in crime. There is no honor among thieves, and that, it appears, was their downfall.

On the last afternoon of their lives, the Egan brothers met with some of their friends, including a Watertown man, Joe Leone. They plotted a liquor truck heistor so the brothers believed. None of the people involved in that nights events had jobs at the time. The Egans had been on the countys public assistance rolls for some time, and Leone was a laid-off trucker.

I had a very revealing two-hour conversation during the spring of 2013 with another party to the New Years Eve plot, James Pickett. He was actually the first person to be arrested in the triple murder investigationthree years and a couple months after the eventand he, turning states witness, provided information that helped police charge three more people: Leone, Willard Belcher and Belchers wife, Bertha. A warrant against Willard was never served, however.

Pickett told me that after the case was closed, he never again talked to anybody about the Egan murders until we had our conversation early in 2013. He had kept it bottled up for nearly forty-nine years. When I asked him why he was talking to me, he replied that I was the only person who ever asked. He told me that he was an old, broken-down man, and he felt it was time to set the record straight before he died. Pickett said it was like therapy getting it all off his chest.

He died on April 15, 2013, a few weeks after our conversation. The resident of Limerick, New York, was eighty-one.

Unfortunately, as the reader will discover in the pages that follow, I eventually learned from a surprise source that Pickett might not have been as forthright with me as he had sounded. Perhaps that is why he said he could tell me things that nobody else knew, but he was afraid his phone might be tapped.

After the triple murder, nobody in the North Country felt safe anymore. The repercussions were felt for miles, even in my hometown of Redwood, thirty miles to the north. The killings changed the way people thought. I had never even heard the word murder until then. The only people I had ever heard of being shot were Presidents Lincoln and Kennedy. I was six years old at the time, in the first grade, and I can remember being petrified. Everybody was.

Rumors ran rampant. It was a Mafia hit was the most popular thought.

I always kept my ears and eyes open, listening to people speculating and gossiping about the Egans and about who might have had a reason to kill them. Peter, Barbara and Gerald had become folk legends in northern New York.

A few months after the murders, my father, William Boyer, took the family for a Sunday drive, which included a stop at the infamous rest area. This, he told us, was where the Egans were murdered. He pointed to some bullet holes in a metal trashcan. I freaked out and started to cry. I wanted to get the hell away from there. I didnt want to get shot in the head.

Around this time, my cousin Toby Donovan and I invented a game we called the Egans Game. We would get in Uncle Johns car and slump over in the front seat, pretending to be Peter and Gerald Egan. We had become infatuated with the killings.

Then, in the summer of 1967, the case got a little close to home for me. My friend Dean Heath and I became acquainted with the Wonder Bread man. It started out one day when Dean told me that the delivery truck drivers were supposed to give free samples if requested. We saw the Wonder Bread truck roll into town and pull up to Lloyds Grocery. We approached the driver and asked, Mister, do you have any free samples?

He handed us a whole box of jelly doughnuts, along with a big smile.

The next week, the truck was in Redwood again. The driver was the same tall, lanky man with thinning black hair who had been so nice to us before. We ran over, and this time he gave us a box of chocolate clairs. We were hooked. It became a weekly ritual for more than a year. We never had to ask for samples again. Toby and I would be playing the Egans Game in his dads car, and then wed run up an alley to the store and bum free doughnuts from our friend Joe the doughnut man.