An imprint of Rowman & Littlefield

Distributed by NATIONAL BOOK NETWORK

Copyright 2015 by Don Brown

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Brown, Don, 1960

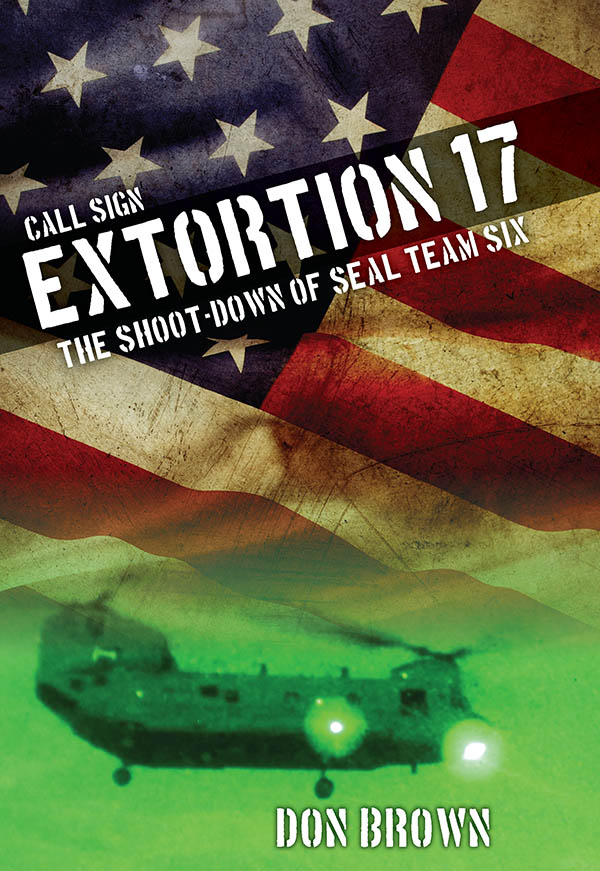

Call Sign Extortion 17 : the shoot-down of SEAL Team Six / Don Brown.

pages cm

ISBN 978-1-4930-0746-2

1. Afghan War, 2001Aerial operations, American. 2. United States. Navy. SEALsHistory21st century. 3. United States. Naval Special Warfare Development GroupHistory. 4. Chinook (Military transport helicopter) 5. Special operations (Military science)United States. 6. Afghan War, 2001Campaigns. I. Title. II. Title: Shoot-down of SEAL Team Six.

DS371.412.B74 2015

958.104'745dc23

2015002084

ISBN 978-1-4930-1732-4 (e-book)

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

Contents

Prologue

base shank

logar province, afghanistan

august 6, 2011

Under the moonless sky in Logar Province, at just before two oclock in the morning local time, thirty Americans, including seventeen members of the elite SEAL team that had killed Osama Bin Laden fourteen weeks earlier, were scrambled aboard a Vietnam-era US Army National Guard Chinook helicopter, code name Extortion 17. Sixty-six years earlier to the day, the United States had dropped an atomic bomb on Hiroshima.

The old Chinook was not the type of helicopter typically used by the SEALs. Special Forces units typically attack with specially equipped, highly armed Special Operations helicopters with highly sophisticated electronic and jamming systems, flown by Special Operations pilots trained to insert the SEALs with swiftness, speed, and surprise.

But the Chinook was not an assault helicopter. It did not have significant offensive capabilities, and it was not designed for high-speed assaults carried out by US Special Forces. The Chinook was a transport chopper and was not designed to fly into a hot combat zone. Its crew was a National Guard crew, trained to transport troops and equipment, but not trained or equipped for Special Operations in hot battle zones.

The Americans boarding the chopper ranged in age from the youngest, twenty-one-year-old Specialist Spencer C. Duncan of Olathe, Kansas, to the oldest of the group, forty-seven-year-old Chief Warrant Officer David Carter of Aurora, Colorado.

Two of the men, Lieutenant Commander Jonas Kelsall, the SEAL commander, and Chief Petty Officer Robert Reeves, had been best friends since their high school days in Shreveport, Louisiana, and even played on the same high school football team.

Sixteen of the men had wives back home in the United States, and thirty-two American children called these men Daddy.

Three of the men, Navy Senior Chief Craig Vickers of Hawaii, Navy Chief (SEAL) Matt Mason of Kansas City, and Senior Chief Tommy Ratzlaff of Arkansas, had wives who were expecting their third child.

Vickers was on his last tour with the Navy and planned to retire and return home to his family in May 2012. Like Craig Vickers, forty-four-year-old Senior Chief Lou Langlais, one of the most highly decorated and experienced SEALs in the Navy, was also on his last combat deployment and planned to return to a stateside job as a trainer where he would reunite with his wife, Anya, and their two boys in Santa Monica.

Seven mysterious Afghan commandos, along with one Afghan interpreter, joined these remarkable Americans on the helicopter that night. The presence of the unknown Afghans, whose names were not on the flight manifest, breached all semblances of military and aviation protocol.

Within minutes of takeoff, every American on board Extortion 17 died a horrific, fiery death in a crash that would mark the deadliest single loss in the eleven-year-old Afghan war, and the single-largest loss in the history of US Special Forces.

Why did these men die?

Their children and wives deserve to know. Their parents and their country deserve an answer.

Powerful evidence now suggests there was a cover-up to prevent the truth from ever getting out.

What is being covered up?

Several signs suggest that the Taliban were tipped off as to the Chinooks flight path and were lying in wait with rocket-propelled grenades as it approached the landing zone. Invaluable forensic evidence has been inexcusably lost, negligently or intentionally destroyed by the military, or conveniently glossed over to obfuscate the truth as to why these men died.

Even if the Taliban had no inside information, which appears unlikely, the decision to order a platoon of US Navy SEALs and supporting troops onto a highly vulnerable and largely defenseless Vietnam-era National Guard helicopter, a CH-47 Chinook piloted by a noble crew of National Guard aviators who were ill equipped and untrained in the Special Forces aviation techniques necessary to prosecute this mission, effectively sealed the death warrants for each and every American on board that night.

For the sake of the thirty-two children who lost their fathers, for the sixteen wives who lost their husbands, for the sake of sixty parents who lost their sons, and for the sake of a nation that deserves better from its leadership in protecting its treasured sons in times of war, hard questions need to be asked.

This is the story of the last flight of Extortion 17 and the cover-up that followed.

Chapter 1

Forward Operating Base Shank

logar province, eastern afghanistan

august 5, 2011

late evening hours

The crescent moon hung low over the horizon, dipping below the mountains off in the distance to the west.

It was 10:00 p.m. local time, and the night was not yet half gone. But soon, the moonless sky would yield to the faint blinking of the stars against the jet-black canopy of space, a placid contrast to the bloody jihad raging in the dark hills and valleys and riverbeds beyond the mountains.

Down below the starry firmament, in this forward-deployed military base occupied by Western forces in the ten-year-old War on Terror, a buzz of activity arose from units of several US Special Forces, namely from US Army Rangers and the elite US Navy SEALs.

Here, in the midst of the Afghan night, they called this place Base Shank, or officially, Forward Operating Base Shank. And at first glance, with its wooden buildings and Quonset tents, concrete barriers and big green and sand-colored jeeps and dirt graders, FOB Shank could pass for 1950s-vintage from the Korean Warperhaps even the backstage of a Hollywood set constructed in the foothills of snow-capped mountains.

But technologically, and militarily, there was nothing Fifties-vintage about this place, nor was there anything about it that was Hollywood.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.