Copyright 2014 by Skyhorse Publishing, Inc.

All Rights Reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

Skyhorse Publishing books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or .

Skyhorse and Skyhorse Publishing are registered trademarks of

Skyhorse Publishing, Inc., a Delaware corporation.

Visit our website at www.skyhorsepublishing.com.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

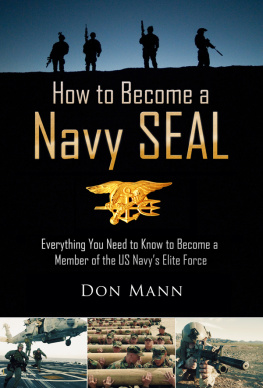

Mann, Don, 1957

How to become a Navy SEAL : everything you need to know to become a member of the U.S. Navys elite force / Don Mann.

pages cm

ISBN 978-1-62087-186-7 (alk. paper)

1. United States. Navy. SEALs. 2. United States. Navy. SEALsVocational guidance. I. Title.

VG87.M25 2014

359.984--dc23

2014015208

Cover design by Rain Saukas

Ebook ISBN: 978-1-62873-487-4

Printed in China

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

The Beginning

For outstanding performance in combat during the invasion of Normandy, June 6, 1944. Determined and zealous in the fulfillment of an extremely dangerous hazardous mission, the Navy Combat Demolition Unit of Force O landed on the Omaha Beach with the first wave under devastating enemy artillery machine-gun and sniper fire. With practically all explosives lost and with their force seriously depleted by heavy casualties the remaining officers and men carried on gallantly, salvaging explosives as they were swept ashore and in some instances commandeering bulldozers to remove obstacles. In spite of these grave handicaps, the Demolition crews succeeded initially in blasting five gaps through enemy obstacles for the passage of assault forces to the Normandy shore and within two days had sapped over eighty-five percent of the Omaha Beach area of German-placed traps. Valiant in the face of grave danger and persistently aggressive against fierce resistance, the Navy Combat Demolition Unit rendered daring and self-sacrificing service in the performance of a vital mission, thereby sustaining the high traditions of the United States Naval Service Presidential Unit Citation, one of three awarded to the Navy for the Normandy landings.

In the fall of 1942, a small detachment of sailorsdemolitioneershaving been given a crash course in cable cutting, commando attacks, and, of course, demolition at an amphibious training base in Little Creek, Virginia, sailed to French North Africa to conduct its first World War II mission: part of Operation Torch, a joint British-American invasion that, if successful, would give the Allies open access to the soft underbelly of EuropeSicily and Italyand ultimately Germany.

Under cover of darkness, the maritime commandos came to the mouth of the Wadi Sebou River in Morocco, 75 mm artillery fire raining down on them from the fortress of the Kasbah. Their mission was to remove the boom and net, held up by a heavy cable, that were blocking the port and the way to Port Lyautey Airfield, occupied by the Axis-friendly Vichy French military.

The operation was perilousheavy squalls, enemy fire, and monster surf threatened to quash the mission of the 17 men in their Higgins boat, a shallow barge-like landing craft. The men reached the net, cut it with explosive cable cutters and raced downstream, gunfire from the Kasbah in their wake. Not one man was hit. The net was swept away, and the USS Dallas rammed through the river boom, unloading its troops, who captured the airfield.

These men, who were part one of the first successful Naval demolition teams, went back to the United States to help the military create more obstacle clearance units. By 1943 orders went out to form special combat demolition units, and swiftly. The enemyGermany and the other Axis powerswould certainly create every manner of obstacle to slow the landing by sea of Allied troops in Axis strongholds such as Sicily, and the coast of Normandy in France. If forced to debark in heavy surf Allied troops could lose their weapons and worse, drown or be shot as they slogged through hip-high water. The Allied amphibious forces needed the support of advance demolition teams. These units would be sent first to the beaches of Sicily and a year later, to Normandy to open channels through the heavily fortified shore prior to the historic D-Day landing there in June of 1944.

Troops wade ashore at Omaha Beach on D-Day, June 6, 1944.

Military orders also called for the creation and training of sailors for permanent naval demolition units. Led by Lieutenant Commander Draper L. Kauffman, who had received the Navy Cross for disarming an intact enemy bomb at Pearl Harbor, allowing the U.S. military to study it, the training program set up at Fort Pierce, Florida, turned out Naval Combat Demolition Units (NCDU) specialists who could map enemy beaches, knock out mines, explode obstacles, and open the way for Allied assaults in the most dire combat.

In the Pacific Theater of Operations, Marines landing on islands and atolls required a different type of assistance than that of the European Theater.

At Tarawa Atoll in the Gilbert Islands U.S. Marines had been met, in November of 1943, with 4,500 well-fortified, well-prepared Japanese soldiers in a bloody scramble to secure that piece of land. The battle left 6,400 Americans, Koreans, and Japanese dead. The Americans gained control of the atoll, but the Japanese had fought down to the man in a show of resistance not seen in earlier amphibious landings. It was clear that in the push to control key islands in the Pacific Marines would need underwater reconnaissance and demolition of any obstructions, particularly the coral reefs that crowded the coastal waters. There was also the possibility of Japanese mines.

Marine demolition teams storm a Japanese stronghold on Betio Island in the Tarawa Atoll of the Gilbert Islands, November 1943.

The first Underwater Demolition Teams (UDTs), One and Two, were created when 30 officers and 150 enlisted men from the SeaBees, Marines, Army Engineers, and others who had trained at Fort Pierce, were brought to Waimanalo Amphibious Training Base on Oahu, Hawaii, and later to a Naval Combat Demolition Training and Experimental Base on Maui. For Pacific missions they had to know how to graph the coastline and blast. And they had to be able to swim long distances. Earlier nighttime reconnaissance had been a failure, so the UDTs had to perform their missions in daylight, and that required strong swimmers, not equipment.

Often in nothing more than swim suits, fins, and dive masks, these brave men participated in every significant amphibious landing in the PacificEniwetok, Saipan, Guam, Leyte, Iwo Jima, Okinawa, Brunei Bay, among others.